In 1892, twelve-year-old Arthur Williams sent a letter to the matron of the Receiving and Distributing Home of the Manchester and Salford Boys and Girls Refuges in Canada. He requested information on another boy, explaining, “the reason why I want to get his address is I want to get a piece of poetry to sing at the Christmas tree.”1 Williams also asked for the address of another boy, whom he knew from his time at the Refuges in Britain. This request was not unique. Many British child migrants asked for other children’s addresses to keep in contact and share knowledge. The extraordinary circumstances of migration and as the ordinary process of growing up called for knowledge about a range of topics. Child migrants, however, were separated from one of the most important knowledge exchange networks: their families. Therefore, they often relied on each other.

Most of the time, we do not have direct access to the knowledge circulating among child migrants. Yet, as child migration agencies such as the Refuges functioned as gatekeepers, their records provide insight into the knowledge child migrants had or sought. Analyzing the processes of knowledge formation and transfer among children who migrated to Canada provides a window into the daily lives and experiences of British child migrants in the late nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. It shows that children were not merely passive recipients of knowledge but active agents within networks of knowledge formation, transfer, and concealment.

Williams had been sent to Canada by the Refuges the previous year. He was one of about 100,000 children who migrated to the British settler colonies—mostly to Canada and Australia—without an adult family member.2 Inspired by religion and imperialism, the child rescue movement set up several government-supported child migration schemes in the late nineteenth century. Child rescuers saw the emigration of poor children, “bastards,” and orphans as a remedy for social problems at home, a method to cope with labor shortages in the colonies, and a means to strengthen the empire. Further, emigration offered a way to open up both spiritual and material opportunities for the children, making them productive members of society. Thus, the children trained as farmhands and domestics on farms, in households, and at farm schools. Child migration to Canada lasted until the closure of the Fairbridge Farm School in British Columbia in 1950.3 Programs bringing children to Australia continued until the late 1960s.4

Many of the child migration agencies circulated their own magazines to facilitate and control knowledge exchange between the children. The Dr. Barnardo’s Homes, for example, published letters and essays by child migrants in Ups and Downs for other and future child migrants to read. The magazine supported the exchange of knowledge about farming, work ethics, religion, and patriotism. In 1900, the editor encouraged emigrated boys to respond to one of their peers in Britain considering emigration. The editor’s claim that all the replies showed a “fraternal desire to share with the sojourner in the land of Egypt the milk and honey of the land of Canaan” certainly speaks for the boys’ desire to see their words in print, not necessarily for their enthusiasm about emigration.5 The advice and information conveyed in the boys’ letters echoed the values and knowledge the agency wanted to disseminate among the children in their care. Samuel Hillman, for instance, wrote:

In order to get along in this country, will depend largely on your disposition [sic]. If you are ambitious and faithful in whatever you do, you cannot help but get along. Be faithful and true to your master and mistress also. . . . [I]f you are a good boy, you need not fear of any bad experience.

Hilman also gave some details about land grants in Western Canada.6

The selection of knowledge encouraged by the organizations, however, was not necessarily what the children already in Canada were most interested in. Many wanted to know how to avoid work, how to leave an unsatisfactory situation, or how to return to Britain—not how to please their employer. In the 1920s, a representative of the Church Army Distributing Hostel in Winnipeg sent a letter to the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization asking for boys awaiting deportation back to Britain to be kept at the government’s Immigration Hall rather than at the Church Army’s Hostel. The reason he gave was that he feared the exchange of certain kinds of knowledge between those being deported and those staying at the Hostel temporarily while between jobs:

A boy for instance who has passed his board for deportation, for continual bed-wetting, comes into contact here at the Hostel with a boy who is a misfit and is being replaced, this boy maybe a wee bit homesick. The boy who is passed the board for the above reason talks to him and maybe says, "Oh, if you want to get home all you have to do is wet the bed for a night or so." The boy being homesick does this and is deported.7

We do not know whether such a case ever occurred.8 We do know, however, that child migrants exchanged knowledge about ways to improve their situations, not all of it accurate. At the Fairbridge Farm School, some girls were desperate to get rid of the school’s unpopular matron. One of the girls later recalled:

Every Sunday we made the Matron's tea with the water we boiled the eggs in. Someone told us that the egg water was poisonous and if we made her tea with that water—she would be poisoned. We felt justified.

The girls’ weekly anticipation was disappointed as the matron survived.9

In 1943, former Farm School student George Hill complained about his placement. His employer had an easy explanation for the boy’s discontent: A former schoolmate placed nearby had less work and much free time, which upset Hill. The boy, by contrast, put blame on his employer: “I do not like the way Mr Clarke is treating me. I do not like the way he hits me and swears at me for the least thing and the hours are to[o] long and the work is unpleasant.”10 Most likely, it was the combination that made Hill unhappy. By speaking to his peer, he realized that he could garner a lighter workload and better treatment with another employer. Hill was not alone. When child migrants met, they frequently compared their wages, and many became dissatisfied by the discrepancy.11 In the end, Hill was persuaded to stay in his situation for another year. He continued to stay in contact with the school and his schoolmates.12

There was another sphere of knowledge most child migrants could only acquire through their peers: sexuality. Child migrants had no parents or siblings to rely on for such knowledge. At the same time, they were at great risk for sexual exploitation.13 Little is known about sex education among children placed with private families. Some probably received knowledge from their employers’ children or by exchanging letters with other child migrants. At the Fairbridge Farm School, up until the mid-1940s, it was the cottage mothers’ duty to explain the facts of life to the children in their care. Many, however, were too embarrassed to discuss the topic.14 After the local doctor, the biology teacher, and the school’s headmaster officially took over the responsibility,15 there was apparently no change in the way most children received their sex education. In 1948, the school’s superintendent of child care, Winona D. Armitage, wrote a report about the high number of illegitimate pregnancies among former female students. She found that ignorance was not the main issue. As far as sex was concerned, “there is much discussion of this between the girls, and it is considered that few, if any, did not have sufficient knowledge even if it was not imparted in the best way.”16

In some cases, the children had knowledge they could use as leverage with adult care takers. In October 1944, John Lloyd, a former Fairbridge Farm School student, sent a letter to the school’s principal, demanding his savings and for his guardianship to be returned to his parents. To lend weight to his request, he wrote:

[O]f course I could mention a few things that were not on the level while I was there, I know a little bit too much about Rogers and a certain Cottage Mother you may know but I don't think Mr. Green [Secretary of the Fairbridge Society in London] does, maybe it would surprise him don't you think so?17

Faced with the threat of delicate information about child abuse leaking to his London superior, the principal promised to grant Lloyd’s requests.18 Nonetheless, a month later, Gordon Green and the Fairbridge Society in London began to discuss the “Rogers case.”19 E. E. Rogers, the school’s former duties master, had been imprisoned in 1942 for sexually abusing two students.20 Which cottage mother Lloyd was referring to in his letter is unclear; many Farm School students later reported ill treatment and abuse by different cottage mothers.21 Most of the time, child migrants were subjected to the agencies’ systems of information exchange and concealment. Lloyd’s example, however, shows that the children could learn to master the systems and use them to their advantage.

Returning to the 1892 request with which this piece began, the response by the matron of the Manchester and Salford Boys and Girls Refuges’ Receiving and Distributing Home was not archived, nor were any letters exchanged between Arthur Williams and any other boy. Williams’ next letter does not reveal whether the matron granted his request either; his descriptions of the Christmas festivities focus exclusively on the presents he received.22 Agencies like the Refuges were generally inclined to encourage children’s (religious) singing and the exchange of related knowledge among them. Child migrants like William cherished music as acoustic memories and a way to bond with other child migrants in a foreign country. While it is unknown whether Williams ever received the piece of music he was asking for, the sources indicate that there was a steady exchange of knowledge among child migrants. Separated from their families and familiar surroundings, they frequently relied on their peers for the knowledge necessary to cope with the challenges of working and growing up in Canada. Through their function as gatekeepers, child migration agencies produced and archived sources that offer insight into the children’s concerns and desires as well as into the knowledge exchange networks and children’s role within them.

To protect the privacy of individuals and their families, British and Canadian law as well as the rules set by The Prince’s Trust (University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296) and The Together Trust (Manchester Archives, GB127) for the use of their archival material prohibit identifying most individuals. Therefore, the following names are pseudonyms chosen by the author: Arthur Williams, George Hill, Mr. Clarke, John Lloyd.

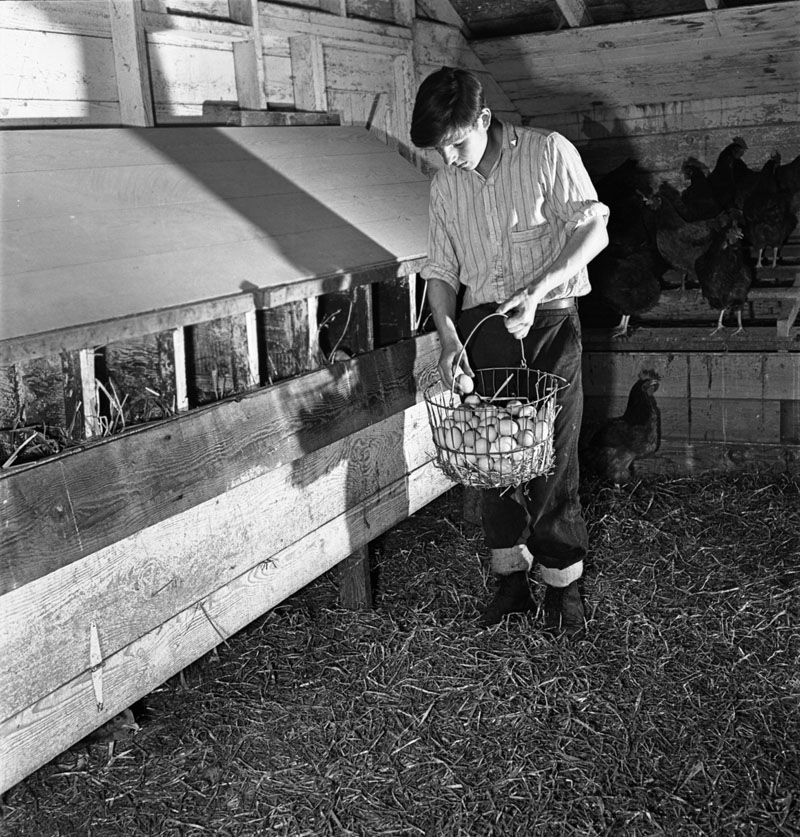

Featured image: “A youngster collects eggs after school, Fairbridge Farm School, Duncan, British Columbia.” Source: Library and Archives Canada, PA-159658.

- Manchester and Salford Boys and Girls Refuges, Emigration Reports and Letters, 1890, 4: 1890–1891, Manchester Archives, GB127.M189/7/3/9. ↩︎

- Independent Inquiry Child Sexual Abuse, Child Migration Programmes: Investigation Report (2018), pt. B, paras. 3–6; Marjory Harper and Stephen Constantine, “Children of the Poor: Child and Juvenile Migration,” in Migration and Empire, ed. Marjory Harper and Stephen Constantine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 248. ↩︎

- The Canadian government ended most child migration schemes for children under the age of 14 in 1925. Patricia T. Rooke and Rodolph Leslie Schnell, “Imperial Philanthropy and Colonial Response: British Juvenile Emigration to Canada, 1896–1930,” The Historian 46 no. 1 (1983): 59. ↩︎

- On the British child migration schemes, see Ellen Boucher, Empire’s Children: Child Emigration, Welfare, and the Decline of the British World, 1869–1967 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014); and Gordon Lynch, Remembering Child Migration: Faith, Nation-Building and the Wounds of Charity (London/New York: Bloomsbury, 2016). For the Fairbridge scheme in particular, see Geoffrey Sherington and Chris Jeffrey, Fairbridge: Empire and Child Migration (London: Routledge, 1998). ↩︎

- “Our Literary & Mutual Improvement Society,” Ups and Downs (Toronto) 5, no. 3 (1900): 67. ↩︎

- Ibid., 73. ↩︎

- The Church of England in Canada, The Church Army Juvenile Emigration Distributing Hostel, Winnipeg, Man. to Department of Immigration and Colonization, “Letter Re: Boys for Deportation; Re: Boys Who beyond Doubt Are Not Suitable for Farming and Are Very Unhappy in Their Present Circumstances; Re: Boys under Our Supervision; Re: Location Maps,” December 1927, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), RG 76, vols. 372–73, file 504791, pt. 5. ↩︎

- The Church Army repeatedly complained about long waiting periods for deportation, which put an administrative and financial burden on the agency. See The Church Army, London, England (Empire Settlement Act) (Lists), 1928, LAC Ottawa, RG76, vol. 373, file 504791, pt. 6; herein, e.g., H. M. Speechly to A. L. Jolliffee, ‘Letter Re: J. Taylor, Church Army Hostel (Copy for General File Regarding the Church Army)’, 17 September 1928, LAC, RG 76, vol. 373, file 504791, pt. 6. ↩︎

- “Egg Water for Tea,” Fairbridge Gazette, Christmas 2006, 15. ↩︎

- Fairbridge Farm School Administrative Records (hereafter: Fairbridge), BC Archives, MS2045. ↩︎

- British Oversea Settlement Delegation to Canada, Report to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, President of the Oversea Settlement Committee, from the Delegation Appointed to Obtain Information Regarding the System of Child Migration and Settlement in Canada: Presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Parliament by Command of His Majesty December, 1924 [= Bondfield Report] (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1924), Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch, RG 76, vol. 51, file 2209, pt 4. ↩︎

- In 1950, he asked for the school’s magazine, “so that I have an idea of how thinks [sic] are happen [sic] over there,” and for two schoolmates’ addresses. Fairbridge, BC Archives, MS2045. ↩︎

- On the risks for female child migrants sent to Canadian farms and households, see Joy Parr, Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to Canada, 1869–1924 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1980), 114 and 116. On the risks for all child migrants sent to institutions, including the Fairbridge Farm School, see Independent Inquiry Child Sexual Abuse, Child Migration Programmes. On the risk for female child migrants after leaving institutions, see Senate Community Affairs References Committee Secretariat, Parliament of Australia, Lost Innocents: Righting the Record: Report on Child Migration Australia (Canberra, 2001), para. 4.31. ↩︎

- Winona D. Armitage, Report on Illegitimate Pregnancies of Fairbridge Girls, 1948, p. 2, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 B5/3/4; Geoffrey Thomas, Kingsley Fairbridge Farm School, Pinjarra, W. Australia: Confidential, p. 6, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 J1/2/3. On the late 1940s, see The Fairbridge Society, Report on Co-Education: With Special Reference to the Farm School System of Home Care (London, 1947), p. 19, BC Archives, MS 2469, box 1, file 3; and W. J. Garnett, Co-Education in Relation to Farm School Life & Work (Private & Confidential), University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 K1/3/7. ↩︎

- The Fairbridge Society, p. 19; Mary Lenore Schofield, “Letter ‘Dear Family,'” June 17, 1946, BC Archives, MS 2459, box 1, file 5. ↩︎

- Armitage, Report, p. 2. ↩︎

- Fairbridge, BC Archives, MS2045 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Fairbridge Farm Schools (Inc.), Minutes of Meeting of Executive Committee Held at Savoy House on November 8, 1944, at 3.0 p.m., 1944, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 B1/2/5, 68–72; Gordon Green, Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School, Cowichan Station, Vancouver Island, British Columbia: Analysis of Case and Comments, 1944, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 K1/2/10. ↩︎

- Harry T. Logan, Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School: Principal’s Report: Annual Meeting, Wednesday, November 17th, 1943 (Confidential), 1943, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 K1/3/13. ↩︎

- For example: Roddy MacKay, “Who Took the Fair out of Fairbridge,” Fairbridge Gazette, Summer 2000, 7–10; and Eric Lewis, “Eric Lewis’ Response to the President’s Summer Message,” Fairbridge Gazette, Christmas 2007, 13–14. For contemporary reports critical of some cottage mothers see, e.g., Thomas; and Tempe C. Woods, Points for Consideration by Perth Committee, 1943, p. 2, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, D296 J1/2/3. ↩︎

- Manchester and Salford Boys and Girls Refuges, Emigration Reports and Letters, Girls: 1889–1893, 1889, Manchester Archives, GB127.M189/7/4/2. This boy’s records were kept in the collection for girls because he had emigrated with his sister. ↩︎