Introduction to the Society of Jesus and Its Missions

During the early modern period, hundreds of Jesuit missionaries left continental Portugal to minister in colonies in the Americas and East Asia. Their migration pattern was male, religious, and mainly “internal”—even though they crossed oceans, giving it a very specific nature even if it was not unique. As a cultural historian, I study the circulation of knowledge inextricably intertwined with these movements that occurred on a global scale but also often within the Portuguese Estado da Índia and always within the Society of Jesus.1

Together with Prof. Christoph Nebgen, my mentor at the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, I am currently working on an edition and translation of sources from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Questions form the very core of every type of research, but this project focuses not on the questions historians pose. Instead, we explore the questions that the historical actors themselves confronted. Faced with contingencies and opportunities, the Jesuit missionaries had to determine answers to these questions in order to secure a missionary assignment abroad; once accepted, they faced further questions. Our findings will be published next year in our book Interview with the Missionary: Frequently Asked Questions for Jesuit Petitioners for the Indies (Boston: Institute of Jesuit Sources, forthcoming).

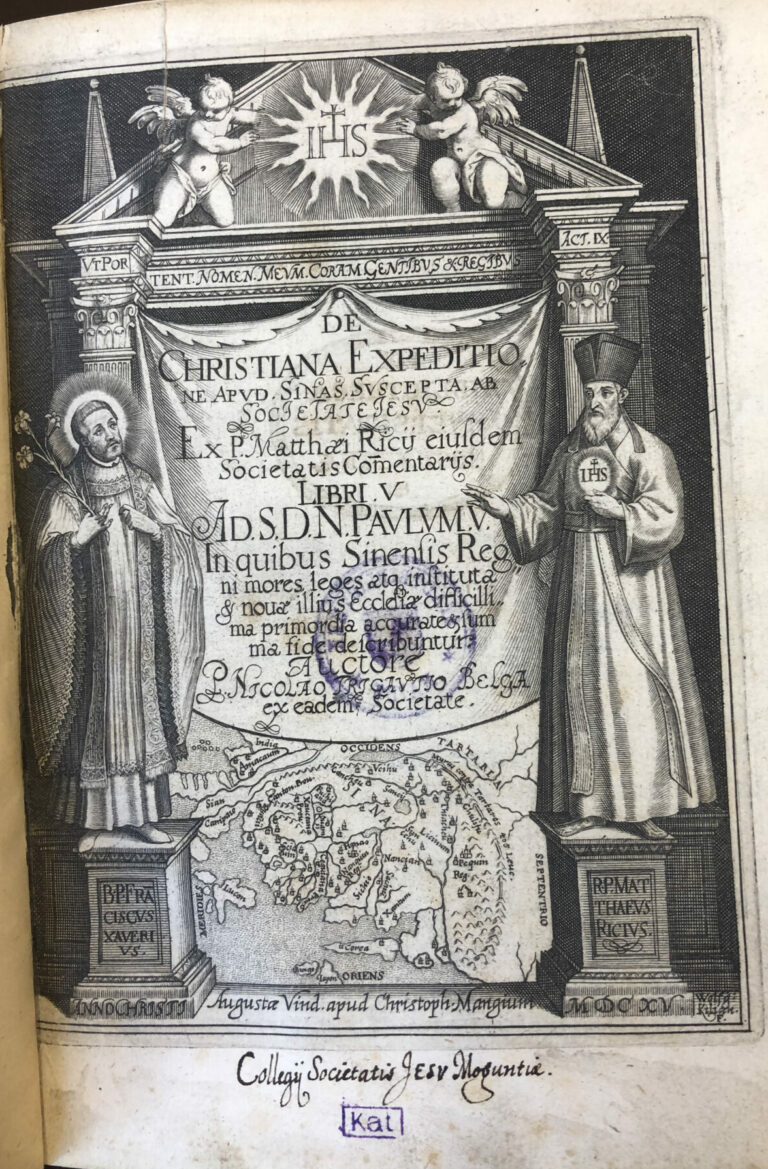

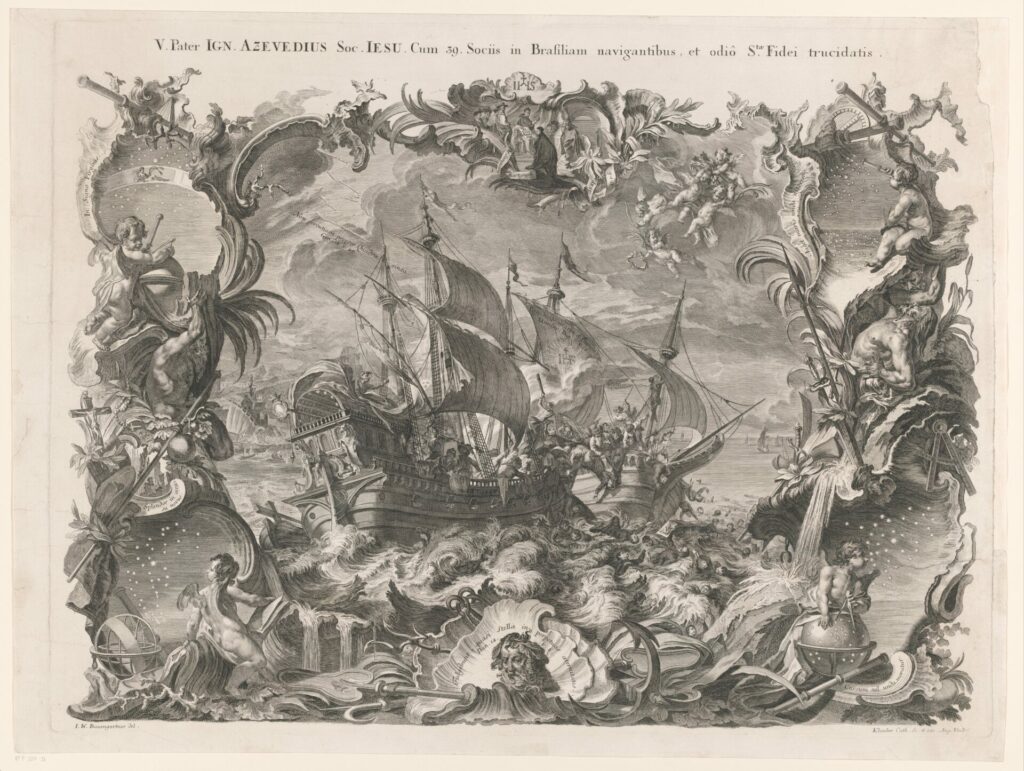

Since it was founded in 1540, the Society of Jesus has been famous among Catholic religious orders for its devotion to education and apostolic ministries—that is, its overseas missions.2 Jesuit leaders carefully promoted evangelical activities, publishing letters and books that provided Europeans with information and curious facts about new lands and people the Jesuits had encountered, often for the first time. Such missionary narratives intrigued readers, including the young students in the order’s European schools, prompting thousands of them to not only enter the Society of Jesus but to petition to minister abroad. More than twenty-four thousand of these petitions, the Litterae Indipetae (because their authors were Indiam petentes, or people asking for the Indies), are preserved in the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu.3 These personal letters have generated considerable interest from scholars in many fields, including cultural studies, religious history, the history of emotions, and psychology. These sources, when considered with the replies issued from Rome, demonstrate how Jesuits navigated complex negotiations—within and outside their religious order—that determined whether they would serve as missionaries.4

FAQs

Litterae Indipetae contained young men’s deepest and most sincere passions. Some were written or at least signed in blood to demonstrate the authors’ devotion.5 These documents show how the Society of Jesus, as a modern Human Relations office, developed a system for evaluating the thousands of applications received each year from across Europe.

To submit convincing petitions, aspiring missionaries needed to describe every phase of their “career” within the Society of Jesus—what they studied and where, which subjects they taught, and which “jobs” they did as Jesuits: carpenters, cooks, painters, and so on—and then explain how the mission would fit into this career. The following paragraphs list the concerns the petentes brought up before, during, and after applying to join missions.6 They did not live in a bubble but read up as much as they could to gather information to improve their chances. What’s more, if a missionary came to visit their residence, they would “interview” him, asking all sorts of questions about the missions, which tended to differ according to the application phase. Such visitors often provided invaluable feedback, as indicated in italics:

1st phase—prior to and during the application procedure:

o Which is the best month to send an Indipeta? Not January, because Rome receives too much mail in that period.

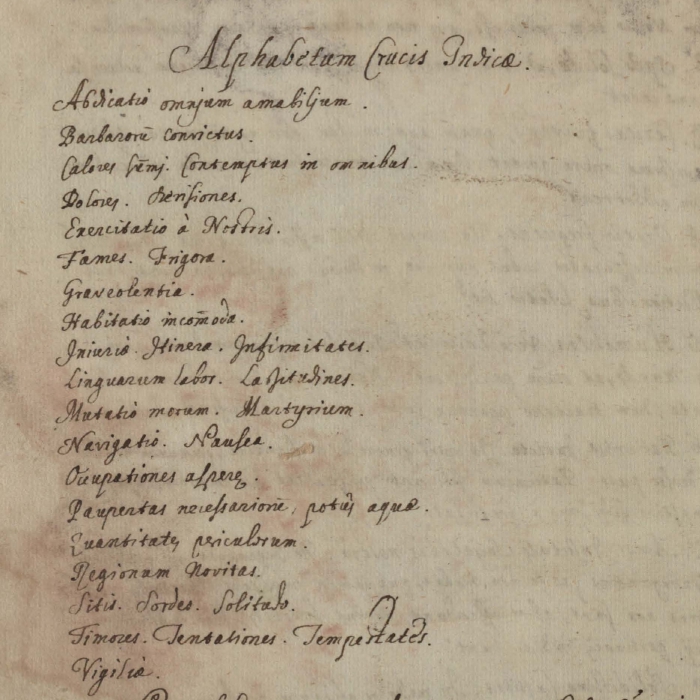

o Which characteristics does a Jesuit need to become a missionary specifically in the East Asian area? The “Alphabet of the Indian Cross” alphabetically lists all the unpleasant feelings you will encounter. Your soul must thus be able to bear them all: pain, mockery, hunger, cold, seasickness, insults, thirst, loneliness, temptations…(see photo above).

o Which subjects should I focus my studies on to become a more suitable candidate? If you want to go to the Chinese missions, math and astronomy.

2nd phase—when a Jesuit’s application had been accepted:

o Is it recommended that I take leave of my relatives once I have received permission to depart? Highly discouraged because they will try to change your mind in any possible way.

o How can I convince my parents that, as a missionary, I am not a commercial intermediary or a post agent, so that I cannot deal with mail, business, and money? You must remind them of the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience that you made when you became a Jesuit, which prohibit you from taking on any mundane tasks.

o What do I put in my suitcase?

Food: dried bread, wine, sausages, sugar, sweets, biscuits, cheese, eggs, pasta, almonds, nuts, and preserved fruits;

To sleep a travel mattress, a pillow, and a blanket;

Clothes: three warm clothes and two socks (you can donate what you did not need to the poor, keeping just the linen robes);

Religious paraphernalia: images of Christ, Mary, and the saints; relics, medals, rosaries, and emblems;

Medicines: everything you will not be able to find there, like “Imanuelis pills”7

Gifts to ingratiate the favors of the “gentile” (not Christian) governors: geographical maps, amber, pearls, bracelets, glasses, crystals, optical tubes, mirrors, and astronomical books.

3rd phase—after a Jesuit reached his destination:

o Where are the best places to spend a safe night after arriving in China, a notoriously dangerous country in which the presence of a European man was easily spotted? There is a place Jesuits usually stay in.

o How do I prevent disappointment if I am sent to the most remote missions but, instead of dealing with indigenous people like I expected, I am told to stay at the city school teaching to the kids of Spanish and Portuguese settlers? Keep in mind the vow of obedience: your destiny does not depend on you but on God’s will as manifested through your superiors.

o How do I fight the bitterness and melancholy I feel when I am all alone in my mission? Keep in mind your one and only aim, which is also the motto of the Society of Jesus: Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam (For the greater glory of God).

Conclusions

These were very incisive and curious questions that aspiring missionaries needed to have answered. Further questions arise, too, for historians—questions that stimulate discussion about what perspectives and potentials unfold at this intersection of migration and knowledge. In fact, when we think about these questions in context, we can see that the Jesuits brought a great deal of knowledge with them; sometimes they transmitted it into their new life, sometimes they integrated it with the local knowledge, and sometimes they forgot it. What did they learn from their religious predecessors? How important was the information received from their experienced confreres before their departure, and through which channels did this exchange happen? Jesuit migration was not so consistent in terms of numbers of missionaries, but it was constant even if it did not increase over time. It was intellectually relevant as well because missionaries were knowledge brokers for a lay public, and in many cases the first Europeans to study languages and civilizations that were previously unknown. The history of migration has always been made out of real people who had concrete problems and different ways of addressing them. Through these documents, these missionary migrants actively shaped the political, social, and cultural history of the countries they left, just as they shaped these histories of the places they landed through the knowledge they brought with them.

Elisa Frei, PhD, is an assistant professor of Catholic theology and history at the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, and a project assistant for the Digital Indipetae Database hosted by Boston College. Her research focuses on Jesuits who sought (and usually did not obtain) a missionary appointment, especially in East Asia and during the early modern period.

- Dauril Alden, The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond 1540–1750 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996). ↩︎

- John W. O’Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Sabina Pavone, I gesuiti dalle origini alla soppressione (Rome/Bari: Laterza, 2021). ↩︎

- Emanuele Colombo, “Gesuitomania. Studi recenti sulle missioni gesuitiche (1540–1773),” in Evangelizzazione e globalizzazione. Le missioni gesuitiche nell’età moderna tra storia e storiografia, ed. Michela Catto, Guido Mongini, and Silvia Mostaccio, 31–59 (Rome: Dante Alighieri, 2010). ↩︎

- Elisa Frei, “‘In Nomine Patris’: The Struggle Between an Indipeta, His Father, and the Superior Generals of the Society of Jesus (ca. 1701–1724),” Chronica Mundi 13, no. 1 (2018): 107–23. ↩︎

- Elisa Frei, “Signed in Blood: Negotiating with the Superiors General about the Overseas Missions,” Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits 51, no. 4 (2019): 1–34. ↩︎

- These questions are loosely based on three guides that Jesuits drafted with advice on submitting a successful petition to serve overseas: “Pro Candidatis ad Missiones Indicas,” which was edited in Johannes Beckmann, “Missionsaszetische Anweisungen aus dem 17. Jahrhundert,” Zeitschrift für Aszese und Mystik 13, no. 3 (1938): 202–15; “Pro missionariis Indiarum et Americae,” Munich, LMU University Library (UBM): 4 Cod. Ms. 118; Gerónimo Pallas, Misión a las Indias, con advertencias para los religiosos de Europa que la hubieren de emprender, 1620, ed. José Jesús Hernández Palomo (Seville: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2006). These documents are at the core of the abovementioned publication I am producing with Prof. Nebgen, Interview with the Missionary. Professor Nebgen studies the first two, whereas I focus on the third one. ↩︎

- Imanuelis pills were a special German remedy, a popular tonic for treating multiple diseases. ↩︎