Editorial note: Robert Irwin’s contribution differs somewhat from what we typically post at the Migrant Knowledge Blog. It presents the ongoing effort to create an archive containing the stories that have been and are currently being produced by and for migrants who travel from Central America and Mexico to the United States. Containing invaluable insights into the individual responses to changing policies and trends in human mobility, this archive can be of great use in writing the recent history of migratory processes in this part of the world. It can also shed light on how such migrant knowledge was formed and disseminated in the past, as well as on past initiatives to archive such knowledge.

As the US, Mexico, and other countries along the migration corridor between Central America and the United States increasingly enact policies that seek to impede migration throughout the region, those who are determined to seek security continue to defiantly migrate along increasingly fraught and tortuous routes, on journeys that may extend for years. Migrant testimonial narratives shed light on both the damage inflicted by migration control regimes and the strategies employed by migrants to reach their intended destinations.

Below, I’ll introduce a digital storytelling project that aims to document and disseminate migrant knowledge through an online archive of migrant testimonial narratives. Then I’ll draw from some of these digital stories to see what we can learn from migrants’ articulations of their experiences as they navigate contemporary policies that seek to obstruct their mobility.

Archive of Migrant Testimonial Narratives

Humanizing Deportation is a community-based digital storytelling project that documents the repercussions of contemporary border and migration control regimes in the United States and Mexico. Since its launch in early 2017, it has published digital stories (testimonial audiovisual shorts) of over 370 migrants in a bilingual (English-Spanish) public online archive.

In designing this project, Guillermo Alonso Meneses of El Colegio de la Frontera Norte and I chose to adapt the methods of digital storytelling to the context of mass deportation in order to capture migrants’ own views on the damage being done by harsh immigration laws and policies. We believed migrants’ first-person narratives would represent their experiences from very human perspectives that studies based on quantitative data or legal analysis might fail to capture.

To be clear, digital storytelling should not be confused with documentary filmmaking, or with journalistic or ethnographic interviews, all of which tend to filter migrant knowledge through predetermined research questions, hypotheses, or arguments. Humanizing Deportation instead offers migrants a platform to tell their stories as they believe they ought to be told, giving them the opportunity to share whatever information they want the world to know. Our fieldwork teams are trained to avoid intervening in shaping migrants’ stories, assuming instead the role of facilitators who assist community storytellers in realizing their vision. We then disseminate their stories via our website and public events. We insist that those best positioned to comprehend the effects of border control regimes on migrants’ lives are migrants themselves, and we train our academic collaborators to listen closely to migrants and to help them to express the embodied knowledge they attain as migrants.

By late 2018, as attention in both the United States and Mexico shifted from the detention and deportation of undocumented or otherwise deportable migrants to the arrival of large numbers of asylum seekers at the US southern border, we expanded our project to include the stories of migrants in transit northward through Mexico. In meeting migrants in transit, we quickly realized that the stories of asylum seekers often implied the constant threat of deportation, and that forced repatriation often figured directly in their migration narratives.

We believe that the Humanizing Deportation digital archive is the world’s largest qualitative database of migrant feelings and migrant knowledge; several members of our research team recently published the book Migrant Feelings, Migrant Knowledge: Building a Community Archive (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 2022), drawing attention to some of what we learned by listening closely to the stories of migrants. This public archive is being consulted more and more by researchers interested in understanding contemporary dynamics of migration from the perspectives of migrants themselves (see Academic Articles).

The lengthy and complicated story of a migrant family who shared their story with the Humanizing Deportation project brings to light a range of issues. Their relentless will to reach their goals helps them assess the mistakes they made as novice asylum seekers and obtain the wisdom of experienced migrants.

Migrating in an Era of Deterrence

A young auto mechanic from Choluteca, Honduras (we’ll call him “Juan”), had to close his shop due to extortion and threats from a criminal gang. He also feared retaliation after testifying as an eyewitness to a kidnapping and then being denied police protection. When he heard about a large group of migrants setting out from San Pedro Sula for the US border in October of 2018, he joined the caravan.

Traveling by caravan was praised by many observers as a safer means of migrating than hopping cargo trains, as many Central American migrants often did, or paying exorbitant fees to coyotes, who increasingly are affiliated with organized crime. However, Juan, who recorded his story just a few days after arriving at the Tijuana border in November of 2018, complicates this view: he highlights his lack of trust in those who seemed to be leading the caravan, as well as his suspicions that organized crime had “infiltrated” its ranks. He went so far as to leave the caravan and take one of the cargo trains, collectively known as La Bestia [the beast], for several legs of the trip. Ultimately, he realized that traveling this way was much more dangerous and returned to the caravan in Mexico City, yet he never felt at ease with all of his fellow travelers. Upon recording his story, he had signed up on an asylum wait list and was looking forward to initiating his case in the US soon after.

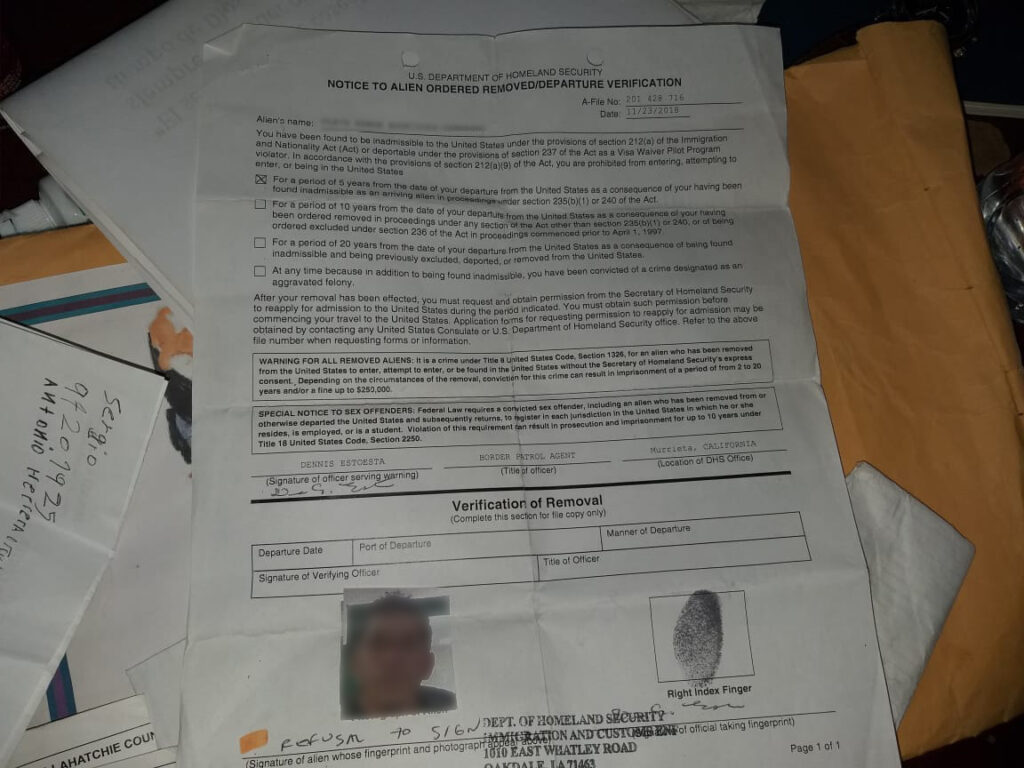

Juan later heard that he didn’t need to wait for his name to come up on the wait list but could file an asylum claim anytime by crossing to the US at any unauthorized point on the border, turning himself in to border patrol officers, and asking to file a claim. Although the information he had received was not incorrect, it was incomplete. When he crossed without authorization, he was indeed picked up by the border patrol and taken to a detention center. However, he had not been given any advice on asylum processes or criteria. In his credible fear interview, he told the officer about the extortion threats and was promptly shut down. He did not prioritize telling them about his vulnerability as a witness in a criminal trial, and before he had a chance to do so, they had ended the interview and were presenting him with a voluntary removal form. When he refused to sign, they grabbed his arm and forced him to place a thumbprint on the form, where they indicated that he refused to sign, and proceeded to deport him back to Honduras anyway.</p

Afraid to remain there, he quickly set out again, this time joined by his pregnant wife and young son (we’ll call them Isabel and Carlitos). They got as far as Chiapas, Mexico, but as they neared the border with Oaxaca, they were caught by Mexican immigration agents and taken to a detention center. The Honduran consulate initially prevented their deportation due to Isabel’s advanced pregnancy. However, since Mexican authorities had resolved to deport Juan anyway, the couple managed to obtain authorization for the family to be deported together.

Once back in Honduras, they left again for Mexico, making it as far as Huixtla, Chiapas, where Isabel gave birth to a baby girl (we’ll call her Susi), whose birth on Mexican soil made her a Mexican citizen. Humanizing Deportation recorded a second installment of Juan’s story, along with Isabel’s own version, some six months after the first recording, in mid-2019.

Soon after the birth of Susi, the family moved to Monterrey, Nuevo León, where Juan had been offered a job as an auto mechanic. A few months after their move, in late summer 2019, they decided that Isabel and Carlitos might try their luck. Mother and son traveled to the border at Reynosa/McAllen, unaware that the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program would require them to “remain in Mexico” throughout their asylum process. After registering their asylum case, they were returned not to Reynosa but to Nuevo Laredo. Those border crossings were apparently controlled by two different criminal syndicates; Isabel had been given a password to return to Reynosa, but when she didn’t present the correct password for Nuevo Laredo, she and Carlitos were kidnapped.

It was difficult for the couple to raise funds to pay the ransom. After Isabel’s mother sold her house back in Honduras, Juan made the required payment and secured his wife and son’s release. Still determined to reach the US, Juan hired a coyote who helped him cross the border, requiring him to move to Tennessee to work off the money he owed. Isabel, terrified of the cartels of northeastern Mexico, moved with the children meanwhile to southern Mexico.

Soon after the change of presidential administration in the US in 2021, migrants whose MPP cases had been abandoned were permitted to enter the US to complete them. Isabel and the children took advantage, returning to the US to reopen her asylum case, joining Juan in Tennessee in March of that year. In February of 2022, having moved to California, Juan recorded a new story in which he expressed his belief that California would offer a friendlier environment for immigrants. Isabel recorded her own new installment as well, noting that she was pregnant again and looking forward to her new baby being born in California.

These latter installments of their story end on an upbeat note–the family presents a happy ending to a migration saga that had begun nearly three and a half years earlier, involving migration by caravan, via freight train, and with the assistance of coyotes; detentions and abuse by border authorities, and, ultimately, deportations from both the US and Mexico; a kidnapping; the birth of two children; and both authorized and unauthorized border crossings. What the family does not emphasize is that their story is far from over: Isabel and Carlitos had not yet had her first date in asylum court, and Juan remained undocumented. Even though it might be possible to contest the legality of the circumstances of his removal (his voluntary removal form indicates “refusal to sign”), his return to the US, an “illegal reentry,” is considered a felony and puts him at risk of imprisonment and deportation.

Conclusions

This family’s migration story reveals that their inexperience put them in difficult and dangerous situations, but it also shows the strength of their determination. Furthermore, as their story has developed year by year, they have gradually become more aware both of dangers lying in their path and resources available to surmount them. Their relentless will to find security in the United States eventually got them to their destination and allowed them to pose, in a moment of triumph, as a happy immigrant family. However, the logistical complications they faced along the way, and the traumatic consequences these entailed, offer poignant evidence of the damage inflicted by contemporary regimes of migration deterrence along the Central America-US migration corridor.

We’ve tried to disseminate these stories and what we’ve learned from them however we can. Since we load the videos to our website using YouTube, people can easily come upon them while surfing the web. In addition, we do our best to reach a wide audience through news articles and interviews. Migrants themselves may find our videos, or see them when our teams project them in shelters that we visit, or when partner organizations such as the Red Franciscana para Migrantes disseminate them through their networks (see our collaborative project Migrar Informado Es Migrar Más Seguro [Informed Migration Is Safer Migration]). While the archive may not provide all the information every migrant needs to know, at the very least it helps cultivate a sense of imagined community and lets migrants know that people care.

Robert McKee Irwin is a founding member and Deputy Director of UC Davis’s Global Migration Center. Specializing in border and migration studies, Mexican and Mexican American cultural studies, and gender and sexuality studies, he has been the Principal Investigator and Coordinator of Humanizando la Deportación since 2016. Recent publications include, as co-editor, a special issue of Tabula Rasa titled “Complejos industriales fronterizos globales: genealogías, epistemologías, sexualidades” (2020).