Throughout the nineteenth century, universal exhibitions were world-class events designed to unite people from all corners of the world while showcasing the latest advancements in technology, science, and arts in their national pavilions to reflect the “state of progress” in their places of origin. However, material culture displays aren’t solely representations of uncontestable facts as they always involve the business of negotiation and value judgment with profound political implications.1 Thus, beyond being mere expositions, world’s fairs were highly contested arenas where national elites fiercely competed for the position that their nations ought to occupy in the modern world.

The Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893, one of the most significant fairs of the nineteenth century, celebrated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Opening in May and running through October, the six-month event attracted twenty-seven million visitors. It is estimated that approximately one in five U.S. Americans visited the fair, setting its reputation as the most successful American fair ever staged.2 Taking place at the height of U.S. imperialism, the exposition has been widely viewed as a symbolic assertion of the United States’ rising status as a global economic and political superpower.

Ecuador was one of forty-six countries invited to exhibit at the fair, with its participation showcased in a national pavilion within the Agriculture Building. During a time when social Darwinism was pervasive in popular thought, coastal cacao-exporting economic elites associated with the National Liberal Party, who were key drivers of the national economy, used this public platform to promote a national narrative aligned with their own agendas. Central to this was the desire to attract European and North American migration as a solution to the country’s economic stagnation, which they believed stemmed from the “racial” inferiority of its Indigenous populations.3 To achieve this, Ecuadorian representatives edited El Ecuador en Chicago, a book distributed in the national pavilion, featuring photographs and descriptions that portrayed Ecuador as a land of opportunity, rich in resources and poised for progress.

In this blog entry I explore the strategies employed by the authors of the book El Ecuador en Chicago to attract foreign migration, with a particular focus on the representation of agricultural land in the coastal region and the portrayal of peasants and Indigenous farmers. Through this lens, I aim to highlight the complexities of nation-building in Latin America, where elites attempted to counter global prejudices against their countries while simultaneously silencing or misrepresenting Indigenous peoples.

Ecuador in the Late Nineteenth Century

At the time of its participation in the fair, Ecuador was governed by a progressive administration that sought to bridge deep regional divides between Catholic conservatives in the highlands and secular liberals on the coast. Meanwhile, European and North American industrialization had opened a global market for chocolate, sparking a surge in Ecuadorian cocoa exports and establishing the country as the world’s leading cocoa producer. As coastal cacao exporters associated with the National Liberal Party grew wealthier from this boom, they began to challenge the traditional power of the conservative Quito-based ruling classes, demanding the secularization of the state; the elimination of barriers to international trade; and the modernization of the country’s economic, social, and political structures.

One key to the expansion of liberalism in Ecuador was to define national identity in relation to the global community. Coastal agro-mercantile tycoons, in particular, sought external validation of Ecuador as a “civilized” society to secure foreign investment and commercial success in the emerging global market.4 Implicit in their agenda was the goal of attracting white North American and European migrants, believed to be able to “dilute” the perceived disadvantages of Indigenous and Black populations, thus aiding in the country’s transformation and “civilization.”5 International platforms like world’s fairs were seen as ideal for achieving this goal.

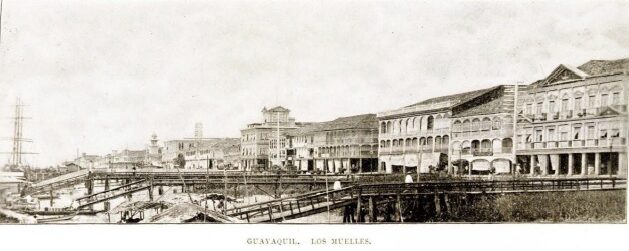

While cacao exporters largely saw the outside world as a source of opportunities, external perceptions of the country often contradicted this hope. At a time when tourism had yet to become the global industry it is today, Ecuador was relatively unknown, and most foreigners who visited the country were likely mountaineers, naturalists, or priests seeking to gather information on natural resources or conduct evangelizing missions.6 However, the poor state of roads, extreme weather conditions, and widespread poverty left many travelers with negative impressions of the young republic. These impressions were often shared with the literate populations of the United States and Europe through travel journals that echoed their prejudiced views of the South American nation. For instance, the popular accounts of U.S. journalist William Eleroy Curtis painted a grim picture of Ecuador, describing Guayaquil as having “dirty streets” with a “repulsive smell” and noting that the “half-naked Indians” were “continually scratching their bodies for fleas and their heads for lice.” He further characterized Ecuadorians as dangerous, claiming they would “stab you or rob you as soon as your back is turned,” and dismissed the country as “the most backward, ignorant, and impoverished in all America.”7

Aware of these negative reports, the newspaper Diario de Avisos de Guayaquil, led by intellectuals, politicians, and cacao entrepreneurs associated with the National Liberal Party, took on the task of editing El Ecuador en Chicago. The publication was intended to circulate in the Ecuadorian pavilion at the fair, countering the unfavorable claims of foreign travelers, while showcasing “concrete evidence” that progress was a latent reality in Ecuador. Luis Felipe Carbo, the newspaper’s director, edited the volume, offering a comprehensive overview of Ecuador’s geography, history, economy, and infrastructure, along with essays by influential figures such as ambassadors, bankers, and the future liberal president José Luis Tamayo.

Ironically, despite the authors’ intention to present a polished national image, the publication was not completed in time for the fair, failing to fulfill its propagandistic mission. After compiling the content, the book was edited as a “remembrance” of Ecuador’s participation in the fair, with two chapters added detailing the Columbian Exposition and the Ecuadorian Pavilion. Carbo used the introductory section to express his frustration over delayed photographs, missing essays, and the book’s limited budget. The publication was ultimately dedicated “with affection and gratitude to the most indulgent and generous of patrons: the Ecuadorian people.”8 The manuscript was sent to a New York printing house for a single print run. Today, El Ecuador en Chicago is a valuable record of nineteenth-century Ecuador and a rare bibliographic relic.

Importing “Civilization”: Immigration Promotion at the Fair

One of the clearest demonstrations of the United States’ global dominance at the fair was evident in the agricultural exhibitions. The farm machinery section conveyed the imperialist notion that U.S. products were “civilizing” commodities, aimed at spreading prosperity to the world’s “unfortunate” regions. Central to this portrayal was not only the technology itself but also the image of the white farmer as a civilizing agent. Promotional materials credited American farmers as the driving force of U.S. economic progress, suggesting that civilization could be achieved through American colonization and its technological expansion.

Receptive to these ideas, Latin American governments viewed world’s fairs as opportunities to manipulate the racial composition of their populations. Many representatives concluded that the solution to the political, social, and economic afflictions of their countries resided in attracting white immigrants, who, once informed of the natural beauty and fertility of their lands, the representatives believed, would rush to recreate a “little Switzerland” on Latin American soil.9 In this context, El Ecuador en Chicago presents Ecuador as a land of promise for European migrants, who, in exchange for access to fertile agricultural land, would contribute to national modernization:

The wastelands are immense and are there waiting for the axe to knock down the corpulent trees so that humankind can plant the grain that produces excellent fruits. Foreign immigrants would find in this republic ample fields in which to exercise their activity. In Europe, the population is too numerous and cannot provide sustenance, while in Ecuador the products of the earth are lost for lack of consumers. It falls to the government to encourage the importation of industrious and useful foreigners, thus aiding humankind, which complains so much of the bad distribution of fortune, the means of providing it for itself and of accelerating the progress of a rich and generous nation.10

Despite coastal elites’ representations of Ecuador as a land of abundance and as an attractive alternative for those seeking to escape the inconveniences of an overpopulated Europe, the country’s negative reputation abroad posed a significant obstacle. Guayaquil, in particular, was notorious as one of the most disease-infested cities in the world. In the nineteenth century, unlike other Ecuadorian cities, Guayaquil’s death rate exceeded the birth rate due to outbreaks of yellow fever and bubonic plague, discouraging potential migrants.11 To alleviate the anxieties of foreign migrants, the book’s narrative attempts to discredit these reports, offering a sanitized portrayal of the city that contradicts the alarming statistics circulating abroad:

We lack, then, honest and sufficiently motivated immigration to discard the exaggerated fears that infuse them about the climatological conditions of the Ecuadorian coast. Hygiene and salubrity are gaining ground, since, for example, in Guayaquil, the provision of drinking water and the partial drying up of the swamps on the outskirts of the city have somewhat modified the climate, thus decreasing mortality, the proportion of which is far from what is generally supposed.12

The described unsanitary conditions that deterred foreign migration did not have the same impact on local migration. By the late nineteenth century, even though the concertaje system13 absorbed much of the Indigenous labor force in the highlands, the cocoa boom triggered the largest internal migration wave in the young republic’s history. Because of this internal mobility, the population of the coastal provinces increased sevenfold by the turn of the twentieth century, from around 150 thousand to over a million. These populations were largely comprised of Indigenous highland workers, who were attracted by the higher wages on coastal plantations and in some cases coerced by cocoa farmers who negotiated their relocation with highland landowners.14

Given this context, it is striking that El Ecuador en Chicago represents the nation as lacking the necessary labor force, despite the fact that labor demand on the coast was virtually met. While Indigenous workers were essential to the national economy, the book’s authors had reservations about portraying them in their narratives, fearing it would deter European migrants attracted to promises of high wages and a familiar European culture rather than the “exoticism” of their destination countries.15 Despite the essential role of Indigenous labor in agricultural production, including in cocoa cultivation, the book conceals the presence of Indigenous peoples in agriculture, and in the few instances in which they are mentioned, they are reduced to a static element of the rural landscape:

The humble peasant of the Ecuadorian coasts, even though he does not enjoy all the freedom he enjoyed in the times before the conquest, lives in the midst of abundance. Lying on the rough hammock of his modest hut, usually surrounded by numerous offspring, and exhaling, in sad laments, the grievances of a conquered race, this dethroned king of the fertile countryside lazily lets himself be. Happier, however, the unfortunate Indian of the high mountains is not worried about the present or the future because he knows that he has bread at hand and, with little effort, the earth gives him new fruits. The profusion of nature tends to dull the faculties of the man who enjoys them, who does not sharpen his wits to produce, unlike what happens in towns with a rigid climate and ungrateful soil.16

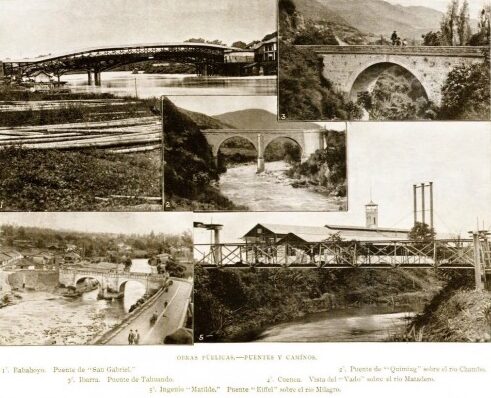

This depiction of rural life in Republican Ecuador bears little resemblance to the reality faced by its population. In fact, nearly all major infrastructure projects completed in the nineteenth century, such as roads and railways, were carried out by Indigenous labor, something that was reported by foreign travelers as well, one of whom observed that “the Indian does more work than all other races together, but his position in the social scale is in an inverse proportion to his usefulness.”17 Additionally, the representation of the “laziness” and “lack of ingenuity” attributed to these individuals reflects ideas from climate determinism, by which certain peoples are perceived as inherently deprived of moral and intellectual advantages due to the latitude they inhabit. These perceptions of foreign lands as “uncultivated treasures” that would be better utilized in the hands of European migrants legitimized colonial occupation and, in many cases, the expropriation of peasant and Indigenous lands.

Conclusion

In conclusion, El Ecuador en Chicago offers a revealing glimpse into the ambitions of late-nineteenth-century Ecuadorian liberal elites who intended to use the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition as a platform to promote migration from Europe and North America. By presenting the Ecuadorian coast as a land of opportunity, the publication sought to counter negative reports circulating abroad, while simultaneously constructing a national image that excluded Indigenous peoples. In this way, this narrative is a double exercise of legitimation and subversion of the hierarchical orderings portrayed at the Columbian Exposition: on the one hand, it challenges the subordinate place assigned to Latin American nations in the global order, while reinforcing local inequalities by denying Indigenous populations a role in the country’s modernity, on the other. Although the publication failed its mission by not reaching its international target audience, it is important to discuss its contents as they expose the enduring legacies of racial ideologies that continue to shape social, political, and economic inequalities in contemporary Ecuador. The exclusion of Indigenous peoples from national narratives has been central to their marginalization, impacting their political representation, citizenship rights, and ongoing territorial displacement. Understanding this legacy is crucial for addressing Indigenous struggles in the present.

Erika Rosado Valencia is a PhD candidate in the Department of Romance Philology at the University of Friedrich-Alexander Erlangen-Nürnberg. Her research interests encompass language and identity in the Andean and Amazon regions, 19th-century travel literature, nation-building processes, and both material and immaterial cultural heritage. Her work has been published in journals such as the Journal of Postcolonial Linguistics and the Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies.

- Sharon Macdonald, The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture (New York: Routledge, 2010), 1. ↩︎

- Stephen J. Whitfield, “Frontiers of the World’s Columbian Exposition,” in Meet Me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader, ed. Laura Hollegreen, Celia Cearse, and Rebeca Rouse, 83–95 (Pittsburgh: ETC Press, 2014), 92. ↩︎

- Blanca Muratorio, Imégenes e Imagineros (Quito: FLACSO, 1994), 173. ↩︎

- Blanca Muratorio, “Images of Indians in the Construction of Ecuadorian Identity at the End of the Nineteenth Century,” in Latin American Popular Culture since Independence, ed. William Beezley and Linda Curcio-Nagy, 121–36 (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012), 124. ↩︎

- Nicola Foote, “Race, State and Nation in Early Twentieth Century Ecuador,” Nations and Nationalism 12, no. 2, (2006): 261–78, 265. ↩︎

- Christa Olson, “Contradictions of Progress: Visions of Modernity, Infrastructure, and Labor in Late Nineteenth-Century Ecuador,” JAC 33, nos. 3/4 (2013): 615–44, 616. ↩︎

- William Curtis, The Capitals of Spanish America (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1888), 300–35. ↩︎

- Luis Felipe Carbo, ed., El Ecuador en Chicago (New York: A.E. Chasmar and Cia, 1894), ix (this and all subsequent translations by the author). ↩︎

- Olga Vilella, “An ‘Exotic’ Abroad: Manuel Serafin Pichardo and the Chicago Columbian Exhibition of 1893,” Latin American Literary Review 32, no. 63 (2004): 81–98, 85. ↩︎

- Carbo, El Ecuador en Chicago, 279. ↩︎

- Ronn Pineo, Ecuador and the United States: Useful Strangers (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007), 141. ↩︎

- Carbo, El Ecuador en Chicago, 291. ↩︎

- Concertaje was a forced labor system in Ecuador that persisted until the early twentieth century, allowing landlords to retain Indigenous workers and their children, compelling them to work the land to repay debts. See Alex Rivadeneira, “The Legacy of Concertaje in Ecuador,” in Roots of Underdevelopment: A New Economic and Political History of Latin America and the Caribbean, ed. Felipe Valencia, 127–62 (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023). ↩︎

- Ronn Pineo, “Guayaquil and Coastal Ecuador during the Cacao Era,” in The Ecuador Reader: History, Culture, Politics, ed. Carlos De la Torre and Steve Striffler, 136–47 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 140. ↩︎

- Sven Schuster, “The World’s Fairs as Spaces of Global Knowledge: Latin American Archaeology and Anthropology in the Age of Exhibitions,” Journal of Global History 13, no. 1 (March 2018): 69–93, 83. ↩︎

- Carbo, El Ecuador en Chicago, 51. ↩︎

- Friedrich Hassaurek, Four Years among the Spanish-Americans (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1868), 188. ↩︎