Editorial note: Recently, Philipp Strobl published a book that examines the migration of ideas and knowledge that Austrian refugees fleeing Nazi persecution possessed and adapted, (A History of Displaced Knowledge: Austrian Refugees from National Socialism in Australia, Brill 2025). Nikolaus Hagen talked to him about this open-access publication and historical perspectives at the intersection of knowledge and migration.

The key historical actors of your new book are refugees from Nazi-ruled Austria, who were forced to flee Europe in the late 1930s and eventually came to Australia. In your book, you highlight the “cultural baggage,” the ideas and knowledge they brought with them, and you ultimately analyze their lasting impact on their new homeland. This is, at least in my view, a very innovative and thus far unusual approach, especially in the fields of Holocaust history and the history of Displaced Persons. How did you come up with your research question and what led you to choose this approach?

I have been interested in the field of migration history for a long time. As you correctly point out, within this field, ideas and knowledge have seldomly been the focus of research. However, this has gradually changed with the emergence of the field known as the history of knowledge. This discipline is particularly well-developed in the German-speaking countries and in Scandinavia. Nevertheless, due to the efforts of the German Historical Institute (GHI) in Washington, it has also become more popular in the United States and the anglophone world more broadly. Indeed, this is also how I was first introduced to the history of knowledge myself, even though I am from Europe. I closely observed the academic developments taking place at the GHI and, in 2016, we collaborated for the first time, organizing a panel at the German Studies Association Annual Conference in San Diego, “Migration and Knowledge: Migrant Knowledge as Profession, Network, and Experience.” This was the third panel in a longer series, all of which addressed the role of knowledge transfers in the migration process.

The further I advanced my research on Austrian refugees in Australia, the more convinced I became of the value of focusing on ideas, knowledge, and cultural capital—in particular, on the translation and adaptation of knowledge by individual migrants, or, more simply, what you referred to in your question as their “cultural baggage.” This approach allows us to analyze how the ability to “play on a cultural keyboard” in the society of origin has shaped the lives and habitus of migrants—in my case, forced migrants—in their new home contexts. It reveals how forced migrants have utilized what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu referred to has human cultural and social capital to restart their lives after the biographical disruptions they experienced, and to cope with phenomena such as downward social mobility and the devaluation of their cultural capital—changes that almost invariably accompanied their displacement.

In the context of forced migration—as evidenced in my study—various forms of cultural capital, such as values, ideas, knowledge, as well as education and qualifications and of social capital—specifically, social networks and interpersonal relationships—have been crucial. They often were the only resources migrants could depend on to rebuild their lives and to forge a positive identity within their new host society—particularly since many forced migrants lost their financial capital during their flight. This was especially true for the refugees from Nazism and the Holocaust I examined in my research. Thus, I believe that employing the history of knowledge approach has greatly enriched my research and, ultimately, the resulting book.

Your book is the outcome of years of research that led you to several different countries and institutions, starting with your initial archival research and your oral history interviews in Australia. You have already mentioned how your collaboration with the GHI positively influenced your methodological approach. Were there other personal encounters with different academic cultures—in Australia, Europe, or the United States—that shaped your research for the book?

My book is a transnational study. Hence, it could not have been successfully realized within the confines of a single country, not only in terms of sources. Naturally, it was intriguing to observe how different individuals dealt with their past in Australia compared to what I experienced in Austria. The refugees in Australia seemed to have tapped into that country’s much more open public culture of discussing the past in comparison to the culture Central Europe. In Austria and Germany, the postwar tendency was, namely, to remain silent about, or avoid addressing, what occurred during the Third Reich.

A crucial advantage of conducting research across different linguistic and academic contexts is the requirement to develop proficiency in multiple research traditions. As I already mentioned, the history of knowledge—with its distinctive terminology—is a discipline primarily recognized within German and Scandinavian research traditions. Memory studies and network studies, as well as biographical research, by contrast, are more fully developed and nuanced in the American academic environment. Beyond this, it is essential to be familiar with the state of research in all relevant regions and, of course, to incorporate this scholarship into one’s study.

Admittedly, this made the research and writing process more complex and lengthened the time it took me to complete the book. Nevertheless, the different schools of thought and various academic disciplines I encountered benefited my work enormously as I was able to integrate insights from each of them. Furthermore, as the book constitutes a transnational study, the manuscript was reviewed by international experts from diverse academic backgrounds. The wide-ranging feedback provided by the reviewers was especially valuable to me and greatly contributed to broadening the approach of the book. I’d like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to them for their insightful comments and suggestions.

“Knowledge” features very prominently in your book’s title and is, unsurprisingly, a key concept for your research. You also mentioned the History of Knowledge as a big influence on your work. While we all seem to have an everyday understanding of what “knowledge” is, it seems to be quite a complex and nuanced concept. Could you elaborate your understanding of “knowledge” beyond the examples you already gave?

In my research, I approach “knowledge” as a broad and multidimensional concept that extends far beyond the simple accumulation of facts or the possession of a formal education. As I understand it, knowledge encompasses both academic and everyday forms, taking shape through experience, cultural practices, social interactions, and collective memory. It is not a static entity but rather a dynamic process—continually adapted, transformed, or even lost as people move between different societal and cultural contexts. Migration, and especially forced migration, shows us that knowledge and cultural capital must constantly be translated and renegotiated. What is considered valuable and useful in one society may lose its relevance, require adaptation, or encounter resistance in another.

For my study, I employed actor-centered and biographical perspectives to analyze not only the transfer but also the transformation of knowledge. I was particularly interested in how migrants themselves remember, reinterpret, and actively promote their knowledge, skills, and cultural capital in new environments. In this sense, knowledge is deeply embedded in social networks and everyday practices and is always subject to processes of recognition, devaluation, or reinvention. By focusing on individual experiences and memories, I sought to reveal the strategies that migrants use to navigate these complex challenges. At the same time, I critically examined both the successes and failures of knowledge transfer.

Thus, I understand “knowledge” above all as something that is created, remembered, and enacted by individuals within specific social, cultural, and historical contexts rather than as abstract information that simply migrates unchanged across borders. Such an understanding enables us to capture the contingent, performative, and often precarious nature of knowledge in motion and to recognize the vital role migrants play as agents and translators of knowledge.

The phrase “migrants as agents and translators” provides a wonderful segue to my next question. Your book is also a collective biography, analyzing the lives of 26 Austrian individuals who came to Australia as refugees from Nazism. How did you find and choose these particular individuals?

From the outset, I aspired to write a “history from below,” giving a voice to individuals who often did not leave clearly discernible traces. It was equally important to me to avoid the potential criticism that the life stories featured in my book were selected arbitrarily, for instance, merely on the basis of source availability. This ambition, of course, made the process of selecting case studies considerably more challenging. I have always preferred a systematic approach to research. Accordingly, I decided to include a prosopographical chapter that provides “hard data” on the overall group of Austrian refugees in Australia to reinforce my selection of subjects for this book. Such an analysis is not easily achievable and may not be possible for every cohort of refugees.

To be honest, I benefited from the past misfortune of others. At the time the refugees arrived, the Australian government practiced a very strict regime of monitoring migrants. Many public officials, such as postal workers or police officers, were instructed to discreetly observe refugees. Their observations, in turn, produced a vast quantity of records, many of which were preserved and have subsequently been stored in the National Archives. Among these materials were naturalization files. These enabled me to quantify Austrian refugees as a group and to characterize them according to criteria recorded in the files, including age, region of origin, marital status, and region of settlement in Australia. Based on this data, I composed a prosopography of Austrian refugees from Nazism in Australia, which became a key component of my book.

This approach constitutes the foundation of my selection process: I chose to focus on one percent of the overall group—26 individuals—who precisely reflected the principal characteristics of the entire population in terms of age, gender, regions of origin and settlement, and so forth. Only after establishing these parameters was I able to search for matching candidates for my study. The ways I identified the individuals were diverse. While I personally researched and contacted some of them, others were recommended to me and happened to correspond to my predefined selection criteria. Additionally, I located some through genealogical databases. Some of these individuals were still living at the time of my research; for example, I was fortunate to be able to conduct an interview with a 95-year-old man. Others had participated in oral history programs during the 1980s or 1990s, enabling me to draw upon interviews that had already been conducted. I also conducted numerous interviews with relatives, specifically, members of the second generation.

What were the main issues these Austrian refugees from Nazism faced when they came to Australia? Could you summarize some of the key findings of your study? Did their issues and difficulties differ from other groups of migrants in Australia, or were they quite similar?

This is a very broad question. The refugees faced multiple challenges before, during, and after entering Australia. It was very hard for them to get a visa in the first place. The Australian government required them to have a sponsor or at least a certain amount of money to prove that they would not be a burden to the state. Also, most of them were deprived of their financial capital. The journey to Australia was very expensive, and the refugees first had to find ways to finance their journeys.

In Australia, there was initially no refugee status. This means that refugees were treated as regular migrants, and there was very little understanding for their situation as victims of Nazi repression. Some even reported public accusations of them being spies for Nazi Germany. Also, there was antisemitism in the country. It did not look like the murderous racial antisemitism the refugees faced in Europe, but they had to deal with it as well.

Now, about the key findings: My study shows that displacing knowledge is a highly complex and dynamic phenomenon. When Austrian refugees were forced to leave their homeland after the Nazi takeover, they lost almost all their economic capital but brought with them a wealth of cultural and social capital—such as education, professional expertise, cultural habits, and, most importantly, social networks. Initially, this knowledge and experience often went unrecognized or was even devalued in Australia due to language barriers, qualifications not being accepted, and cultural differences.

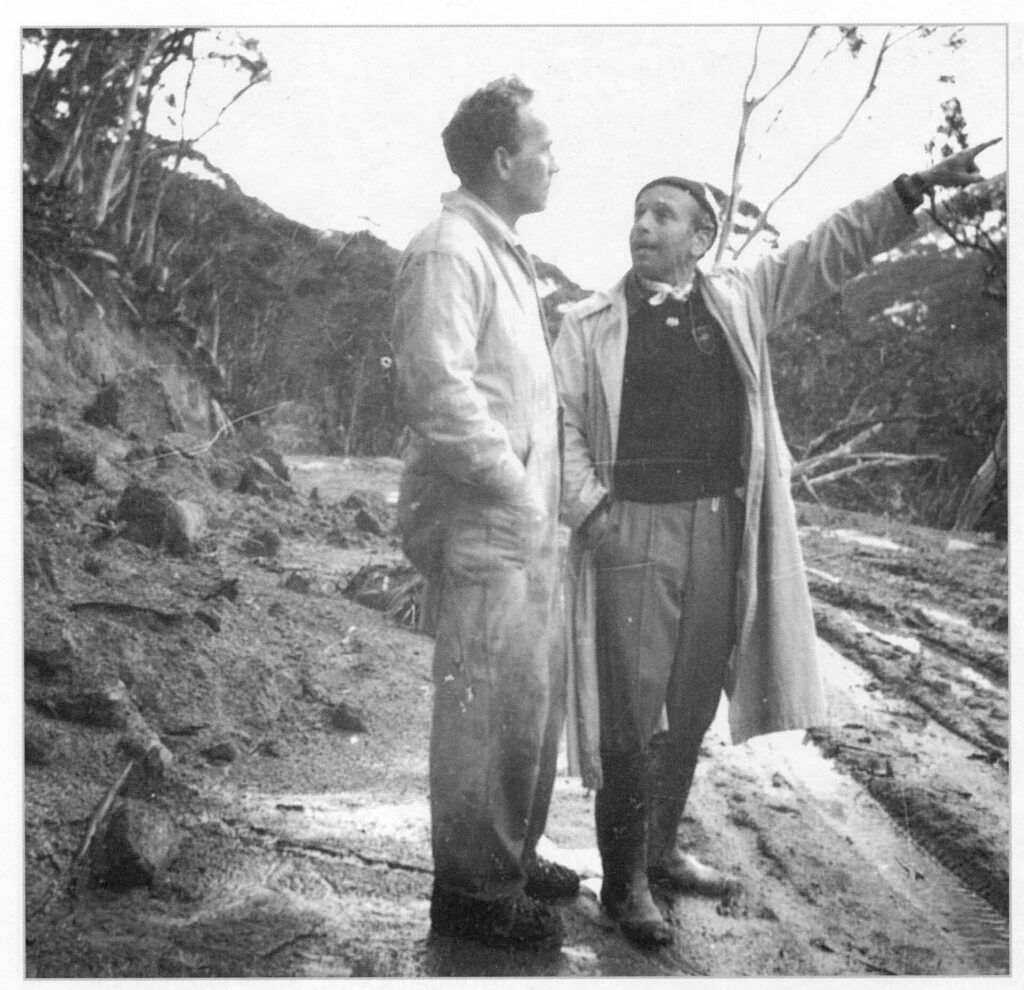

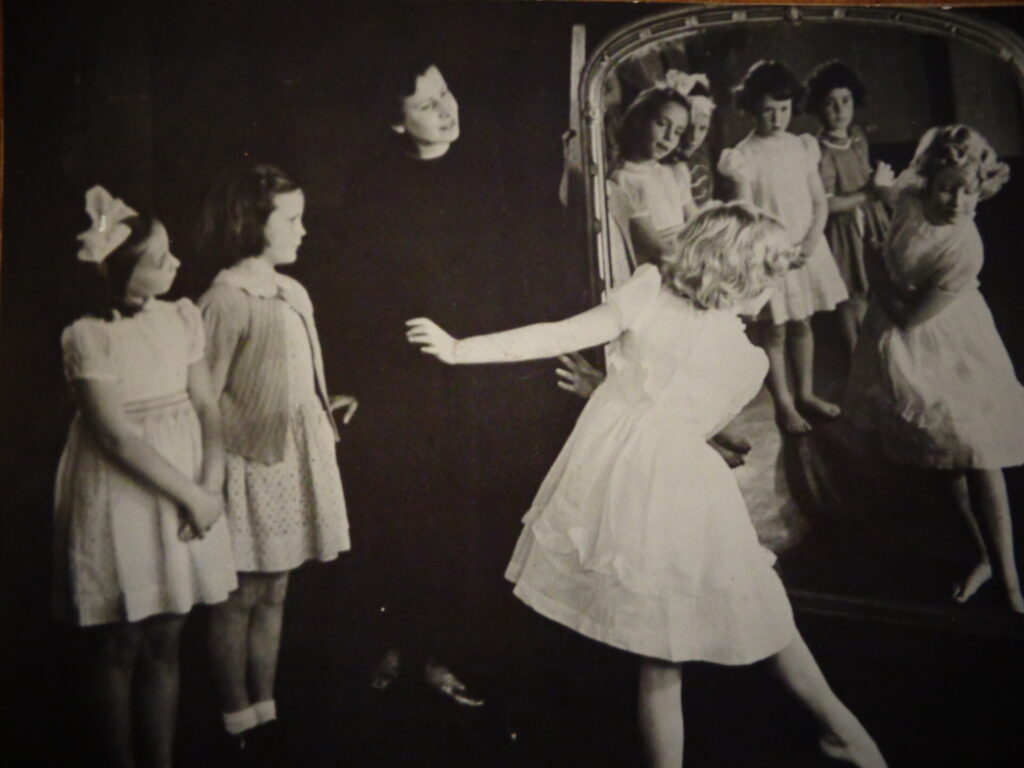

However, the refugees’ success in building new lives depended greatly on their ability to adapt and transform their knowledge to the new environment. Social capital—support from family, friends, religious groups, and professional contacts—proved vital in both escaping Europe and establishing themselves in Australia. Many began by sharing knowledge within their own migrant or religious communities, but over time, some managed to transfer their skills and ideas to the wider society, where they contributed to new fields and cultural life. Successful examples of such transformed bodies of knowledge are diverse, and two of them are pictured here: One was an insurance clerk who, after fleeing to Australia, established ski resorts and ski clubs; another was a dancer who was forced to abandon her medical studies due to the Anschluss and, after her escape, went on to develop dance as a form of therapy in Melbourne; finally, there was a furniture dealer who founded a chain of hardware stores in Melbourne. This is just a sampling.

A crucial finding is that knowledge does not simply travel unchanged; it is constantly negotiated, adapted, and reshaped through new experiences and challenges. Over the long term, the imported knowledge and skills of these refugees enriched Australian society, demonstrating that displaced knowledge—though initially marginalized—can become a driving force for innovation and social development if it is recognized and allowed to flourish. Thus, the study underscores how migration, despite its hardships, can be a profound source of renewal for both individuals and host communities.

Thank you very much for giving us a valuable insight into your research process and the resulting book. As you know, I already had the honor of holding the very first physical copy in my hands. It has meanwhile also been published as an open access publication. I hope that the book – either as a download or, even better, a physical copy – will find a wide readership, and I am certain that your methodological approach will inspire further studies at the interface of migration history and the history of knowledge.

Philipp Strobl is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Vienna. His research focuses on the intersection of migration history and the history of knowledge. He is the founder and editor of the podcast Transit. His most recent book, “A History of Displaced Knowledge: Austrian Refugees from National Socialism in Australia, was published in 2025 in Brill’s Studies in Global Social History series. He recently co-edited a special issue, “Lost Knowledge and Migration” with network member and co-founder Swen Steinberg in the Journal of Migration History.

Nikolaus Hagen is an assistant professor of contemporary history at the University of Innsbruck. His research interests include the history of displaced persons after the Second World War.