In the years that followed the First World War, tens of thousands of Sephardi Jews—an ethnic group descended from Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the fifteenth century—migrated out of the crumbling Ottoman Empire and its successor states to build new lives in France. Many settled in the Roquette quarter of Paris’ 11th arrondissement. Bearing the moniker “Little Turkey,” its streets were lined with so-called Oriental restaurants, grocers, butchers, and cafés. One café, Le Bosphore, situated at 74 rue Sedaine in the very heart of the neighborhood, became a veritable center of Sephardi immigrant life and an important space of migrant knowledge exchange.

Many Ottoman Sephardim learned of Le Bosphore prior to their arrival in France, underscoring how the café was both a facilitator and product of migrant knowledge. It was commonly the first stop of newcomers, who had heard rumors of it while still in the Levant, typically in correspondence from a relative or friend who had already journeyed to Paris.1 Several decades earlier, would-be migrants were directed to another Parisian establishment, the Restaurant du Bosphore, through advertisements in the Ottoman Jewish Press. Salonica’s French-language Journal de Salonique and Istanbul’s Ladino-language La Epoka advertised a Restaurant du Bosphore in Paris to their readers in 1897 and 1898, respectively. Julia Phillips Cohen argues that these promotions underscore how diaspora business owners “promoted the Oriental—and Ottoman—self-identification of their clientele.” More than that, they served as transnational vessels of migrant knowledge exchange, informing readers how and where they might find an émigré community abroad.2

New arrivals (typically men who made the journey alone, hoping to earn enough money to pay for their family’s passage in the near future) were often greeted by a member of the Ottoman Sephardi immigrant community upon their arrival at Paris’ Gare de Lyon train station, and led north towards the Roquette quarter and Le Bosphore. For them, the café was a space of initial welcome offering Sephardi immigrants the first glimpse of the community they were joining. More importantly, it extended to them the opportunity to gain knowledge from more seasoned immigrants, who would help them survive in the bustling city, at the time home to nearly six hundred thousand foreign-born residents.

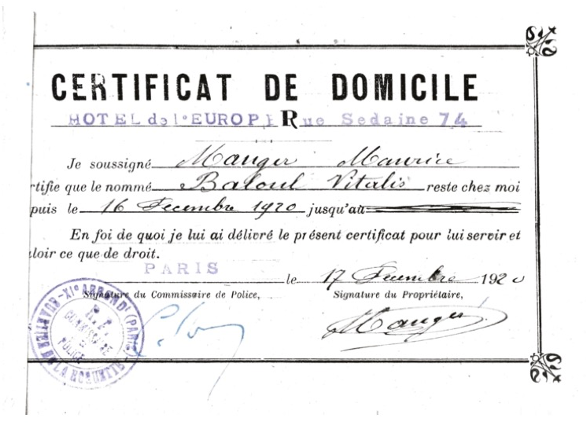

At Le Bosphore, newcomers learned where to find initial lodging in the Ottoman Sephardi immigrant quarter. At times, this would be a spare bed in the apartment of a generous community member. More often, it was a room in one of several furnished hotels located near the café.3 The Hotel de l’Europe, located immediately above Le Bosphore at 74 rue Sedaine, was a common first address.4 Offering minimal but affordable accommodations, furnished hotels became themselves important sites of migrant knowledge exchange in Paris, functioning as spaces that offered not only a roof over one’s head, but also access to surrounding communal networks. Crucially, living there also meant new immigrants had an address with which to apply for government work and residency permits.5

Information about employment was another form of knowledge that immigrants searched for and shared at the café, where more settled members of the community offered work and guidance about certain industries to newly arrived migrants. As the vast majority of Ottoman Sephardi immigrants were poor and unskilled, most opportunities presented at the café were for basic laboring or mercantile jobs. An overwhelming number worked as marchands ambulaires (street vendors) or marchands forains (fairground or market merchants), following the local market schedules and peddling wares (mostly textiles and household linens) acquired from wholesalers in the neighborhood. Merchants in this last group were themselves known to use the café as a make-shift office and warehouse.

For Eliezer Eskenazi of Salonica, who lacked a work permit, connections made at Le Bosphore enabled him to find regular employment under the table as a tailor for “members of the community.”6 Joseph Toros, originally from Istanbul, did “all of his work” at Le Bosphore, according to his son Jacques. It was at the café, not at a brick-and-mortar wholesale shop, that Toros negotiated prices on bulk items that he later sold at markets. Jacques explains, “[t]he merchandise could be anything. Fabric—whatever happened to be at Le Bosphore.”7 The café thus became not only a space of communal gathering but also the site of a micro-economy wherein Ottoman Sephardim networked with fellow immigrants, conducted business deals, and exchanged important economic information (alongside goods and services).

During these interwar years, as greater numbers of Sephardi immigrants from the post-Ottoman lands arrived in Paris, more cafés serving the community opened. They, too, functioned as sites of migrant knowledge exchange. What is more, many new cafés identified with clientele from specific Ottoman regions and localities. Immigrants from Turkey were more likely to go to l’Istambul and Chez Albert.8 Salonicans, on the other hand, went to Chez Sotil, Chez Motola, and l’Athènes. And Bulgarian Sephardim were known to frequent Chez Bouco. At the same time, everyone was said to be welcome at Le Bosphore.9

As the infrastructure of Ottoman Sephardi immigrant cafés in the city grew, their role in the preservation and generation of migrant knowledge became increasingly organized. Communal associations—which expanded greatly in number in these years—held regular meetings at cafés, even using their addresses to register as legal entities with municipal authorities. A group of Ottoman Sephardi veterans who had fought for France in the First World War (the Association des Anciens Combattants Israelites Orientaux) named the Café de la Mairie, located around the corner from Le Bosphore, as the seat of their organization.10 The Sephardi Zionist Association of Paris met monthly at Le Bosphore.11 And La Fraternité, a coeducational youth group, registered the group’s headquarters in 1929 as 81 Boulevard Voltaire, the address of the café Chez Albert.12 Part of the mission enumerated in the last group’s manifesto underscored the broader importance of migrant knowledge exchange: “guiding and advising young immigrants who come to settle in France.”

During the Second World War, Le Bosphore remained an important center of Ottoman Sephardi immigrant life and knowledge exchange. Under the German occupation, members of the community who had been dismissed from the workforce as a result of anti-Jewish “Aryanization” laws relied on Le Bosphore to find informal work, as so many newcomers had done decades earlier. Louise Cohen, at the time a child born in France to Ottoman Sephardi immigrant parents, began to sell cigarettes at the café, doing, as she described it, “little things to survive.”13 As the community faced increasingly dire poverty, the owners allowed patrons to buy meals on credit, thereby continuing the café’s role as a space of communal aid. The café likewise remained a place where knowledge was shared and obtained. Now, patrons shared details about who had been arrested, which apartments had been sealed, which homes or businesses might be suitable hiding places, and when roundups and mass arrests would be carried out.

Its history during the war raises important questions about the limitations of spaces of migrant knowledge exchange, and the vulnerability of the communities that rely upon them. On the morning of May 5, 1944, textile merchant and Istanbul-native Jacques Cohen (of no apparent relation to Louise) heard a rumor from a police officer: that evening, a roundup was to take place at Le Bosphore. In an example of how trying circumstances often result in the production of and reliance upon uncertain knowledge, Cohen passed the information on to his friends, who, like many Ottoman Sephardi immigrants during the war, relied on the café for work opportunities. Together, they decided to visit Le Bosphore before noon and warn the café’s owners and patrons while they were there.14 Tragically, the intelligence had been false. At eleven o’clock that morning, French and German authorities stormed the café, arresting every person inside Le Bosphore. Within days, Jacques Cohen and dozens his fellow Ottoman Sephardim were deported from the Drancy transit camp to Nazi death camps in Eastern Europe.

From the first Ottoman Sephardi arrivals in France in the early twentieth century, Le Bosphore functioned as the Ottoman Sephardi immigrant population’s informational connective tissue. It was a site of cultural preservation and community building, commerce and consumption, socialization and security. It was a space where unofficial work could be found, business conducted, and assistance acquired. Behind its walls, Ottoman Sephardi immigrant patrons found a place where they could share knowledge with their own, separate from the diverse hustle and bustle of interwar Parisian life.

The trust and security that Le Bosphore brought to members of Paris’ Ottoman Sephardi immigrant community persisted into the years of the Second World War and the Holocaust, when the need for knowledge and information carried unprecedented urgency. However, these characteristics were what made Le Bosphore, and its patrons, vulnerable. Indeed, it was precisely because Le Bosphore was known by French authorities and Nazi collaborators to be a space that Jewish migrants relied upon that it became a target and a site of persecution.

Robin Buller is a historian of migration, modern Europe, modern France, and the Jewish Mediterranean. Currently she is a tandem visiting fellow at the Pacific Office of the German Historical Institute Washington (GHI Pacific Office). Her forthcoming book is provisionally titled “Ottoman Jews in Paris: Immigrant Belonging in Interwar and Wartime Paris.”

Featured image: Exterior of Le Bosphore in the postwar period. ©Al Syete (www.alsyete.com)

- In the late nineteenth century, potential Ottoman Sephardi immigrants were told where to find coreligionists in Paris through advertisements in Levantine journals. Both the French-language Le Journal de Salonique and the Ladino El Tiempo advertised another “Restaurant du Bosphore” located in the 9th arrondissement, although no traces of it exist in interwar Paris, and it is not clear whether it has a relation to the rue Sedaine’s Le Bosphore. “Restaurant du Bosphore,” El Tiempo, July 5, 1897, 3; and “Restaurant du Bosphore,” Journal de Salonique, March 3, 1898: 4. Phillips Cohen writes about these classified advertisements and argues that they underscore how diaspora business owners “promoted the Oriental—and Ottoman—self-identification of their clientele.” Julia Phillips Cohen, “Oriental by Design: Ottoman Jews, Imperial Style, and the Performance of Heritage,” The American Historical Review 119, no. 2 (2014): 364–98, quote 378. ↩︎

- “Restaurant du Bosphore,” El Tiempo, July 5, 1897, 3; “Restaurant du Bosphore,” Journal de Salonique, March 3, 1898, 4; Cohen, “Oriental by Design.” ↩︎

- Jo Amiel’s family, for instance, at first stayed with an aunt in St-Maur, a Parisian suburb. Estréa Namer lived with her brother, Robert, upon arrival in Paris in the early 1930s, as he had immigrated to France years before her and had an apartment for his growing family. Testimony of Joseph Amiel, September 12, 2012, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 1, Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine (CDJC); Testimony of Mathilde Pessah, October 18, 2012, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 30, CDJC. ↩︎

- “Lieux de Notre Memoire,” Alsyete, Centre Culturel Popincourt, 2021, http://www.alsyete.com/nos-lieux-de-vie-dans-paris/lieux-de-memoire. ↩︎

- Testimony of René Benbassat, October 12, 2012, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 4, CDJC. Rachel Bardavid’s parents, Joseph Bardavid and Esther née Odjalvo, both of Istanbul, stayed at the Hotel Massif Central on rue Basfroi in the years immediately preceding World War II while saving to rent their own apartment. Testimony of Rachel Bardavid, October 8, 2014, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 42, CDJC. After emigrating from Istanbul and first staying with a family member in a Paris suburb, Avram and Hoursi Amiel stayed at a hotel on rue Trousseau with their infant son before moving to their own apartment. Testimony of Joseph Amiel, September 12, 2012, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 1, CDJC. ↩︎

- Testimony of Léon Eskenazi, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 12, CDJC. ↩︎

- Testimony of Jacques Toros, October 7, 2016, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 65, CDJC. ↩︎

- Located at 68 rue Sedaine, Chez Albert was owned by David Eskenazi, an Ottoman Sephardi immigrant originally from Manisa (Greek: Magnesia) Turkey. Born in 1911, he arrived in France with Turkish citizenship, but was naturalized as a French citizen in 1934 and ultimately survived the war. Registration Card for Chez Albert, 1931, 1945, Section III, III.8.5, Fiches d’enseignes, Box D34U3 2873, Archives de Paris. ↩︎

- Testimony of René Benbassat, October 12, 2012, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 4, CDJC. ↩︎

- Report: Comité d’entente d’associatons d’anciens combattants volontaires juifs en France, April 16, 1941, Series B A, Box 2315, Cabinet du préfet: affaires générales, Dossier 2, Archives de la Préfecture de Police, Paris (APP). ↩︎

- Association des Sionistes Sépharadites de Paris, Series W, Subseries 77W, Box 2717, Dossier 474343, APP. ↩︎

- Report on the Fraternité Israëlite Orientale, Séries W, Sous-séries 77W, Box 1417, Dossier 5679, Renseigenements généraux, APP. ↩︎

- Testimony of Louise Cohen, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 44, CDJC. ↩︎

- Testimony of Gisèle Nadler, Fonds Muestros Dezaparesidos, MDLXXXVIII, Dossier B, Box 3, Item 27, CDJC. ↩︎