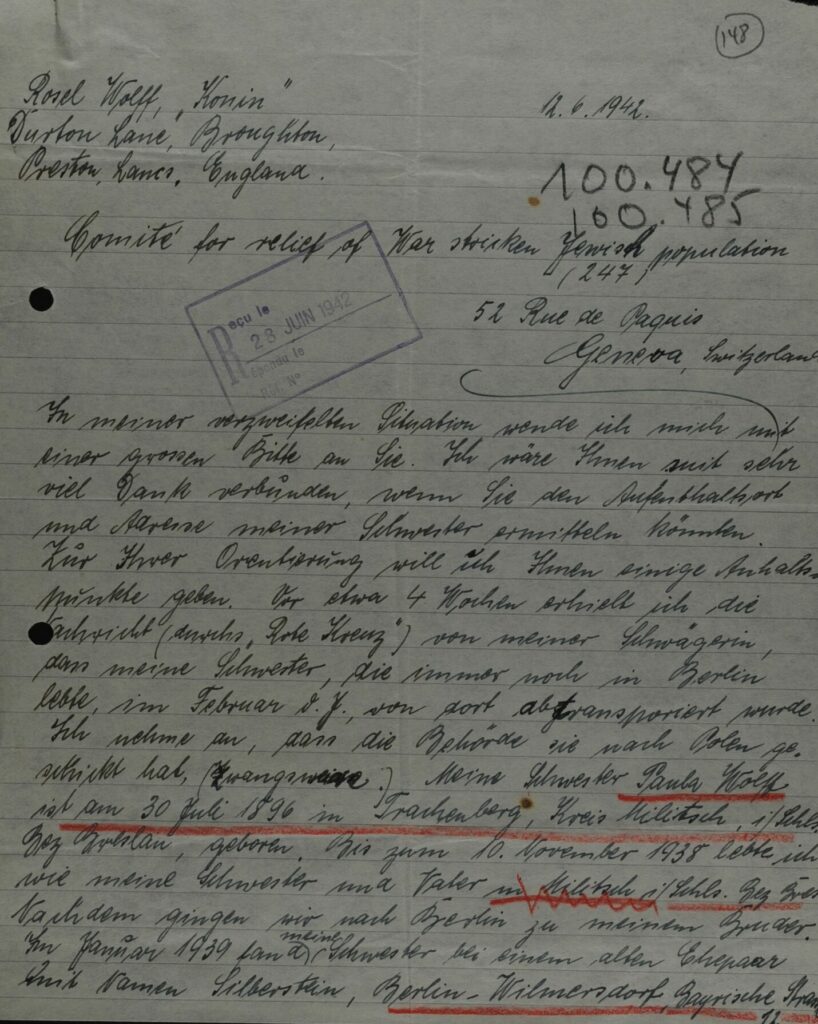

On 12 June 1942, Rosel Wolff (1899–1982) handwrote a letter from her new home in the small village of Broughton in Lancashire, England, to RELICO, the Committee for Relief of the War-Stricken Jewish Population. Having fled to Britain in August 1939, she sought to maintain contact with her beloved sister, Paula (1896–1942), after her brother, Theodor (1905–1978), was interned in Australia as an enemy alien in July 1940, traveling there on the infamous SS Dunera. After receiving news via the Red Cross that her sister had been forcibly taken, Rosel wrote in desperation to RELICO in Geneva in an effort to locate her:

In my desperate situation I turn to you with a big request. I would be very grateful if you could find out the place where my sister currently resides. For your orientation I would like to give you some hints. About 4 weeks ago, I received the information (through the Red Cross) from my sister-in-law [Helene] that my sister [Paula], who had still been living in Berlin, had been transported from there in February this year. I believe that the authorities have sent her to Poland. With all of my life and all of my soul I love my only sister as we have always lived together until an evil fate separated us. … My poor old father had a good place in an old people's home called Brotzen in Breslau, Schweidnitzerstadtgraben [now, it has been planned] to remove even this home to some place. I beg you again from my heart to help me find my sister.1

As it transpired, the information Rosel had received was true, and Paula had been deported to Riga on 19 January 1942. Rosel’s style is typical of many letters sent to RELICO during the middle course of the Second World War, asking for information on a change of address and the nebulous idea of transportation to Poland or “the East.” This letter, and numerous others like it, highlight a desire by many refugees to stay connected to loved ones they were forced to leave behind.

Refugee correspondence with international bodies, such as RELICO and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) during the war, not only links the narratives of “those that fled” with “those that remained” but also demonstrates refugee agency in the search for knowledge of loved ones. Knowledge of their loved ones’ health, well-being, and location was of primary concern, although sometimes merely a sign of life was enough. Often letters addressed to RELICO had the aim of requesting a parcel be sent to a family member in a camp or ghetto, but regularly such messages were coupled with a simple but necessary request for information. This short blog post will utilize a few examples from the archives of RELICO at Yad Vashem to show how Jewish refugees actively sought information on their family members once separated from them.

RELICO and Geneva

From the late 1930s, hundreds of organizations at the local, national, and international level were set up, or redesignated, with apparatus designed to aid in communication across borders and the acquisition of information. For the majority of refugees, the easiest means of confirming family members’ health and location, alongside letting them know of their own well-being, and thus partially alleviating concerns on both sides, was through the Red Cross. Various advertisements published in British newspapers from 1940 onwards speak to this as the purpose of such correspondence:

RED CROSS POSTAL BUREAU, Hawick Office, Where Advice is Given For the Assistance of British Subjects and friendly aliens who wish to ascertain whether members of their families in enemy territory are alive or dead, and, if alive, to inform them of their own health and condition.2

During the Second World War, Switzerland was one of the few places where exchanges between opposing nations could occur, whether that be with people, goods, or information. In his analysis of the Red Cross and the Holocaust, Jean-Claude Favez highlighted the multitude of organizations which based themselves out of Geneva and commented on the close links between them, “ranging from the occasional exchange of correspondence to regular face-to-face meetings.”3 In September 1939, upon the realization by the World Jewish Congress (WJC) that there was a realistic and tremendous danger to many European Jews, the decision was made to combine the political channels of the WJC with the relief efforts of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) under a new WJC subdivision: RELICO.4 According to historian Anne Lepper, the aim of the organization was “to provide quick and direct support to all Jews forced into desperate straits by the war, no matter where they were located.”5

In their aim to provide relief to those affected by the Nazi war machine, RELICO created a network of information exchange across the world initially based on Adolf Silberschein’s connections in Poland. Silberschein was a Galician socialist Zionist who arrived in Geneva in 1939, working at first with Gerhard Riegner but forever treated as the “tolerated foreigner.” As a melting pot of knowledge and connections, Geneva housed other individuals, such as Joseph Thon of the Polish Jewish Refugee Fund, who also used his connections in London and in Warsaw to aid in the support network of those forced to flee.6 Far from being complicit bystanders, individuals and organizations in Switzerland acted positively to ameliorate the situation as best they could.7 Alongside the instructions to send food and parcels to relatives in occupied territory, RELICO also received numerous letters from refugees, such as Rosel Wolff, asking for information on the fate of their family members.

Letters from Relatives: Benno Gottfried and David Klein

In 1942 Benno Gottfried wrote directly to RELICO in English with multiple requests:

Sir! I wrote to you once, asking you to find out the whereabouts about my family. In the meantime I had a letter from my father "Elias Gottfried" who is in Camp de Gurs, unoccupied France. He told me in his letter that the people I am looking for are in Brussels. Could you please be kind enough and find out there exact address, and in case you find them, give them a message "Lilly and Benno" are well. Their names are: "Ignatz and Paula Kohn and their son Siegfried Kohn", Austrians.

I also want to ask you, if it is possible, that you should send my father a food parcel, as he wrote he was serious ill, (Typhus) and needs badly some food. … If it is possible please send it away, and write to me how much I got to pay for it. His addresse is Elio Gottfried, Camp de Gurs, Basses Pyrenees, Plot H, Baraque "23", France

I am waiting your kind reply. Thanking you in anticipation. Yours, Benno Gottfried8

Benno Gottfried (later Ben Godfrey) was born in June 1916 in Vienna to Elio Gottfried (1889–c.1943), a salesman originally from Czernowitz, Romania, and Sophie Kronik from Vilna. Benno had arrived in Britain in February 1939 after his fiancée Lilly Muskovitz (1918–1975) had arrived under a domestic service visa in 1938. Benno, Lilly, and Lilly’s sister Renée (1916–1990) were guaranteed (and housed) by Charles (1909–1976) and Bertha Wilson (1912–1996), butchers from London who grew very fond of the couple, even paying for their honeymoon to Belgium in 1939. Benno’s sister Paula (1914–c.1943) had fled to Antwerp with her husband Ignaz (1907–?), her son Siegfried, and her father Elio in 1938, at the same time as Benno was making his arduous journey through Europe to be with Lilly. Paula, Ignaz, and Siegfried had an affidavit to go to the USA for May 1940—the same date as the Nazi invasion of the Low Countries—but never made it. Benno and Paula’s father Elio was subsequently interned in “the hell of St. Cyprien” on the Spanish border before being transferred to Camp de Gurs, where he wrote frequently to Benno until 1942.9 Whilst unfortunately those letters were lost in the 1970s, the RELICO letter by itself points to Benno’s wish to aid his family from afar, as he had tried numerous times to reach them previously.10

The letter itself is one imbued with knowledge transfer. Benno wished to gain information on the health and location of his sister’s family whilst simultaneously letting her know of his and Lilly’s safe existence in Britain. Based on letters received from his father in Gurs letting him know of the conditions there, and possibly even from national newspapers reporting that “conditions are bad in unoccupied France and worsening,” Benno decided to act upon the information received. Many of the letters received by RELICO speak to this agency, demonstrating refugees’ desire to act upon the piecemeal information received.11

Whilst Benno Gottfried requested a relatively short message be sent to his sister Paula, other refugees who contacted RELICO attached extensive letters, ones that could never be sent directly into occupied territory. In June 1942 David Klein (1896–1982), a former cattle dealer from Eichstetten who fled to Manchester in August 1939, wrote to his beloved sister Betty (1892–1942), whom he believed was in Camp de Recebedou in France, with other members of their family:

My dears! It is Friday night and I have just returned from the shop and would like to finish this letter. I don't know any news and I haven't received any letters from you this week. Ella [David's girlfriend] has given me a present, she really is a very dear girl, I wish you could see her. Last night I spoke to her on the phone, she wants to come around my place tomorrow and we are planning to go out as the weather is really quite wonderful. Now, my dears, have a good sabbath and have my love and kisses, yours, David.12

Betty had previously worked as a clerk in a paper mill in Eichstetten run by Henry Epstein, who was the head of the small Jewish community in the town until he departed for Brazil, whereupon he was replaced by Betty’s brother David. Although the letter, which remained with RELICO, never reached Betty, who was deported to Drancy and subsequently murdered in Auschwitz Birkenau, David, whilst noting the lack of correspondence, instead foregrounded contentment, choosing to highlight the ordinariness of his life as opposed to the extraordinariness of their separation.

Conclusion

The letters of Rosel Wolff, Benno Gottfried, and David Klein are three small examples from thousands of letters sent to RELICO during the middle years of the Second World War expressing concern for family alongside requests for information. Susanne Urban, in her recent article for Medaon, highlighted similar notions in letters sent to the German Red Cross (DRK) during the war, housed in the colossal Arolsen Archive of the ITS. These letters, typified through Urban’s title “Ich bitte innigst um Nachricht von meinem Kinde,” written in July 1941 by Helen Fuchs from Vienna in relation to her son Karl on his way to Palestine, show people wishing to reconnect with family and acting upon their concern.13 Similar projects could equally be undertaken with the recently digitized Ebrei Archival Series of the Congregazione Degli Affari Ecclesiastici Straordinari Collection from the Vatican City Archives, and could also spark the beginning of a more all-encompassing study on refugee attempts to gain information on loved ones during the Second World War.14

The task of contextualizing reams of individual letters for a qualitative research output is difficult. Such contextualization, however, allows us to better appreciate the fragmentary narratives behind each sheet of paper and the requests for information—as Jelena Subotić asks, “What can one piece of paper tell us without a story around it?”15 Knowing the relationship between David and Betty Klein, or the context of separation between Benno Gottfried and his sister’s family in Antwerp, enhances the usability of these letters. Thus, understanding the context and environment of the writer helps us better appreciate the personalized knowledge transfer that occurred on a mass scale.

When the channels of direct communication with family members left behind dried up in 1942, organizations such as RELICO assumed greater importance for those attempting to ascertain whereabouts and a sign of life. Knowledge of continent-wide events affecting swathes of various communities was concentrated into specific familial experiences where relations were tasked with discovering where and how their loved ones fit in to this expansive network. The existence of RELICO, and other communication conduits like it, resulted in knowledge of the Holocaust being personalized for those recipients and writers—a method of expressing concern in a global network of emotions.

Charlie Knight is a Postgraduate Researcher at the Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations at the University of Southampton and is the recipient of the Wolfson Postgraduate Scholarship in the Humanities. His research broadly concerns German-Jewish refugees in Britain during the 1930s and 1940s, and histories of the Holocaust.

- Letter from Rosel Wolff to RELICO, 12 June 1942, YVA M.7/627/148–149, trans. Sabine Endel. ↩︎

- Hawick Express, 31 January 1940, 5. ↩︎

- Jean Claude Favez, The Red Cross and the Holocaust (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 24–25. ↩︎

- Monty Noam Penkower, “The World Jewish Congress Confronts the International Red Cross during the Holocaust,” Jewish Social Studies 41, nos. 3–4 (1979): 229–56, 230. ↩︎

- Anne Lepper, “‘Because I know what that means to you’: The RELICO Parcel Scheme Organised in Geneva during World War II,” in More Than Parcels: Wartime Aid for Jews in Nazi-Era Camps and Ghettos, ed. Jan Lambertz and Jan Lánícek (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2022): 49–77, 54. ↩︎

- See the author’s blog post “Polish-Jewish Industrialists and Their Links to Loved Ones: An Analysis of the Correspondence of Dr Joseph Thon,” EHRI Document Blog, 14 December 2021. ↩︎

- See Raya Cohen, “The Lost Honour of Bystanders? The Case of Jewish Emissaries in Switzerland,” The Journal of Holocaust Education 9, no. 2 (2000): 146–70. ↩︎

- Letter from Benno Gottfried to RELICO, YVA M.7/817/80–81. All spelling and grammatical errors have been left in, unmarked. ↩︎

- Quote from Arno Motulsky, “A German-Jewish Refugee in Vichy France 1939–1941: Arno Motulsky’s Memoir of Life in the Internment Camps at St. Cyprien and Gurs,” American Journal of Medical Genetics A 176, no. 6 (2018): 1289–95, 1292. ↩︎

- Yisrael Geffen, “Memorial Stones – Vienna 2022,” ESRA Magazine (September 2022); Ben Godfrey, interview 41516, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation, London, England, 24 March 1998; Private Collection of Yisrael Geffen, Ra'anana, Israel. ↩︎

- Daily Mirror, 12 September 1940, 11. ↩︎

- Letter from David Klein to Betty Klein via RELICO, 5 June 1942, YVA M.7/952/2–5. ↩︎

- Susanne Urban, “‘Ich bitte innigst um Nachricht von meinem Kinde…’ Korrespondenzen von Jüdinnen und Juden mit dem Roten Kreuz zwischen circa 1938 und 1942,” Medaon 15, no. 29 (2021): 1–14. ↩︎

- Vatican City, Historical Archive of the Secretariat of State – Section for Relations with States and International Organizations (ASRS), Collection Congregazione degli Affari Ecclesiastici Straordinari (AA.EE.SS.), Pius XII, Part I, Series “Ebrei.” ↩︎

- Jelena Subotić, “Ethics of Archival Research on Political Violence,” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 3 (2021): 342–54, 47. ↩︎