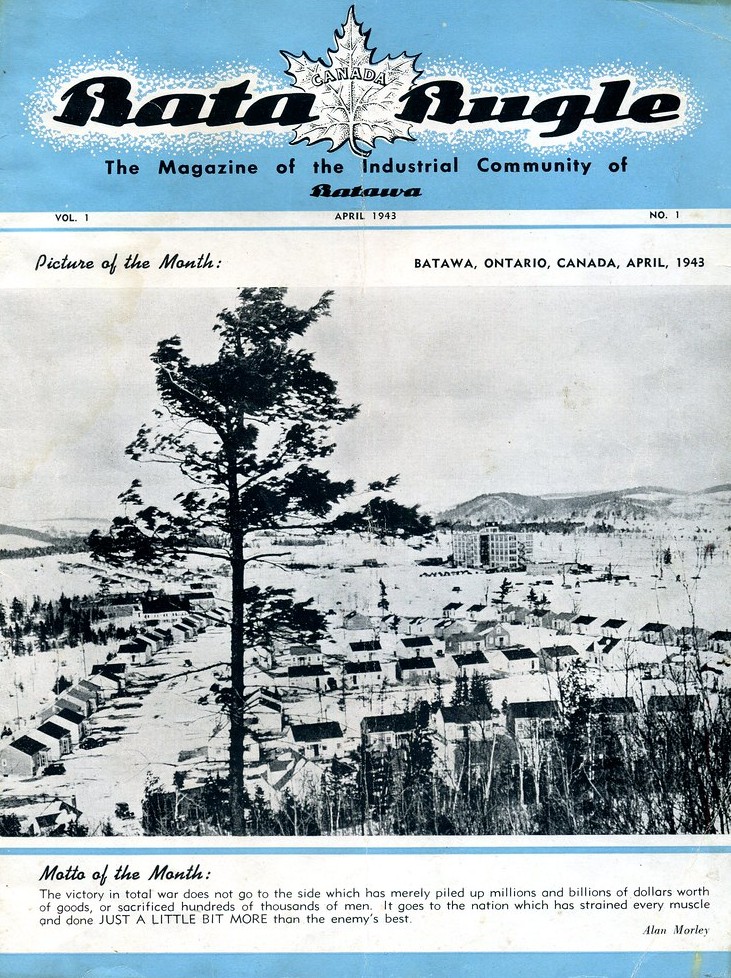

In the fall of 1939, 164 people from Czechoslovakia arrived in Frankfort, Ontario. Ninety-four of them were described as “instructors” from the factories of Tomáš Jan Baťa (1914–2008, later anglicized as Thomas J. Bata) in Zlín – “they had come to start the production of shoe machinery and shoes” in Canada.1 The company had been a global enterprise since 1921 and had significantly expanded its operations after 1931. By then, it employed 25,000 people at 31 locations worldwide, including India, Mexico, Morocco, Syria, and Tahiti. The threat of war, however, prompted Bata to “decentraliz[e]” the global enterprise so it could survive. Between 1938 and 1941, Bata was able to transfer more than 1,000 workers from Zlín to overseas factories,2 including those arriving in Frankfort and their families; the settlement they formed was later called Batawa.

Using this Canadian example of a group of refugees fleeing German aggression in Central Europe, this blogpost highlights knowledge transfers and strategies of knowledge-based adaptation to new economic and political settings in forced migration contexts.

Knowledge, Just Translocated?

Canada’s acceptance of this refugee group was unusual. Still suffering from the impact of the Great Depression, the country had a restrictive immigration policy and a relentless deportation regime; Canada routinely rejected refugees from Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. As antisemitism remained prevalent until the late 1940s, politicians, bureaucrats, and the general public staunchly opposed the immigration of Jews, especially, arguing that “none is too many.”3 Yet, after the failure of the appeasement strategy toward Nazi Germany when the Munich Agreement was reached in September 1938, allowing Germany to annex the Sudentenland in Czechoslovakia, Canada briefly opened its doors to these refugees. In October 1938, German troops already occupied Czechoslovakia’s northern territories. Until World War II broke out in September 1939, Canada continued to accept some internees and child evacuees from Britain but now also a very limited number of refugees, primarily from Czechoslovakia—among them a small group of German-Czech Social Democrats, Austrian refugees, and the individuals who later settled in Batawa.4

But accepting the Bata workers was not merely a humanitarian gesture. Moreover, this group of refugees was white, young (all were “well under thirty”), and skilled, so they fit the white settler-colonial conception of Canadian immigration at that time.5 Additionally, their religious homogeneity suggested a strong sense of in-group identity: the people of Batawa “formed a distinctive Czech Catholic mission amidst a sea of Irish Catholics and Anglo-Protestants.”6

These refugees knew almost nothing about Canada and equally little about the English language. Anthony Cekota (1898–1995, born Antonín) arrived with the group in 1939 and later became vice president of Bata Limited as well as Thomas J. Bata’s biographer. He described the region surrounding Batawa in 1944 as “a paradise on earth” whose hilly landscape reminded the refugees of their home in Czechoslovakia.7 His narrative was influenced by the Central European imagination of wilderness and adventure in a “terra nullius” with “plenty of land and space for pioneering,” where “the footprints of the newcomers were obviously the first.”8 Indigenous perspectives are largely lacking in such refugee-produced sources, which points to the role of ignorance at the intersection of migration and knowledge.9

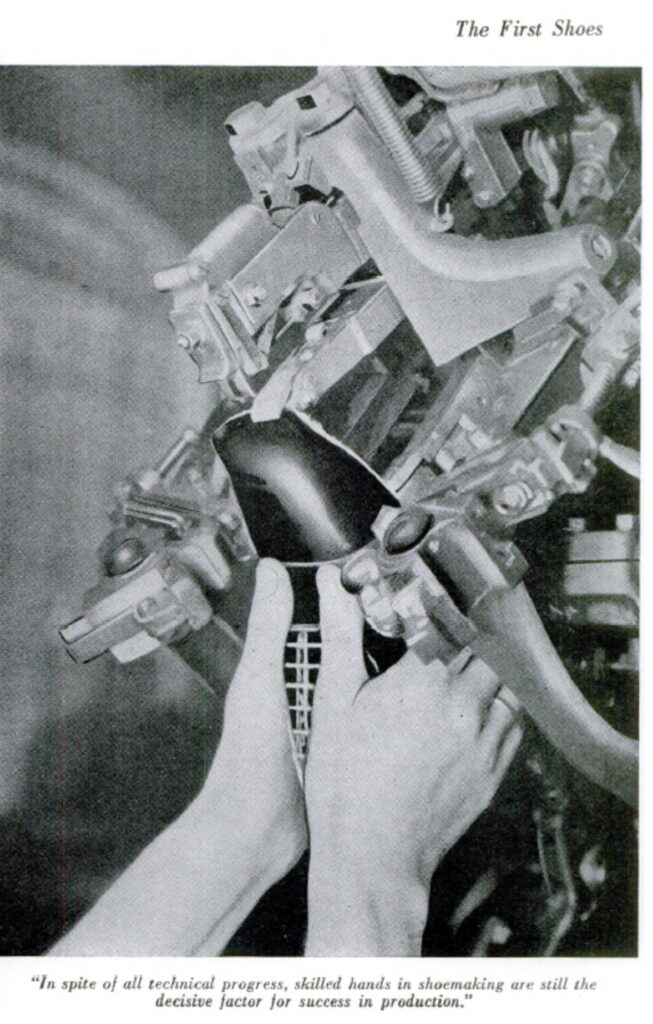

But, most importantly and similar to other immigrants Canada took in, like the timber trader Leon Koerner (1892–1972) from Czechoslovakia,10 Thomas J. Bata brought both specialists and specific bodies of knowledge about production, as well as knowledge about markets. In this context, the need to evacuate workers from Czechoslovakia to escape the threat of Nazi occupation “does not primarily reflect a humanitarian action … but pivots on management decisions.” This is further underscored by Bata’s strategic shift following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 toward “a stricter policy of transferring highly skilled and multilingual personnel overseas.”11 The principle ideas behind the settlement of Batawa were also “teaching local people new skills and management techniques, and the utilization of local raw materials.” Therefore, Bata’s company “chose more and more graduates of its own School of Work” in Zlín in Czechoslovakia for “the process of establishing a new center for its organization in Canada.”12

The Batawa case was unique. Canadians’ reaction to these refugees related to economic considerations beyond the mere “import” of a skilled labor force. But it was also tied to Canadians’ widespread concerns about competition for jobs, especially after the economic crisis following the stock market crash in 1929. It was no coincidence that these workers arriving in 1939 were referred to as “instructors,” suggesting that they brought along specialized knowledge that could not be found in Canada.13 Bata was a global enterprise with access to North American markets; the “import” of its workers’ knowledge, including their practical expertise and experience from one company, may have convinced Canadian politicians and immigration officials to open the door a crack. In addition, these immigrants supposedly felt loyalty toward the country that had saved them. From a strategic, knowledge-driven perspective, Batawa was seen as a win-win situation. However, the new settlement initially generated very few shoes.

Shoes … and Guns

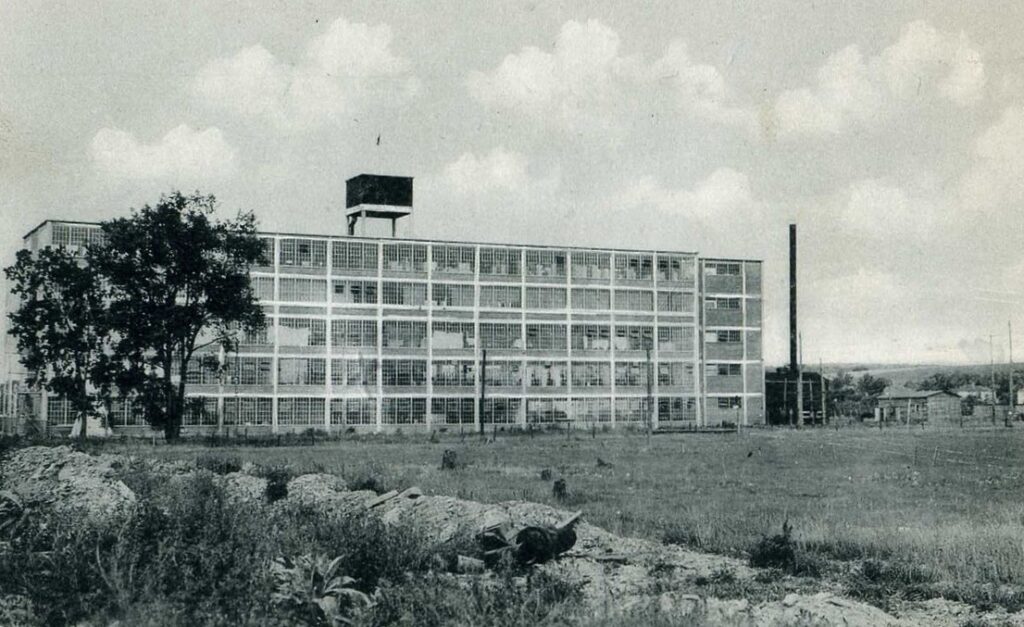

Finding a place for this new Czechoslovakian settlement was not hard for Thomas J. Bata, who arrived in April 1939 in Canada: his company was already operating as a shoe importer and distributor there. But implementing production required skilled workers and machinery from Czechoslovakia; the former needed an infrastructure for living and the latter, facilities for production. This did not spring up from one day to the next, especially since capital transfers from Czechoslovakia were initially limited and later prohibited entirely.14 Even though the company managed to transfer the necessary machinery, it was not easy to start production: Bata started building a five-story factory building and 75 houses for workers’ families; 70 of the first 164 people to arrive were wives and children. By late September 1939, the settlement later named Batawa had 800 inhabitants, and production was relegated to in an abandoned paper mill there. In the following years, the village grew as more Czech workers and their families arrived in Batawa, some of them on long transit routes via Morocco, Brazil, and Haiti.15

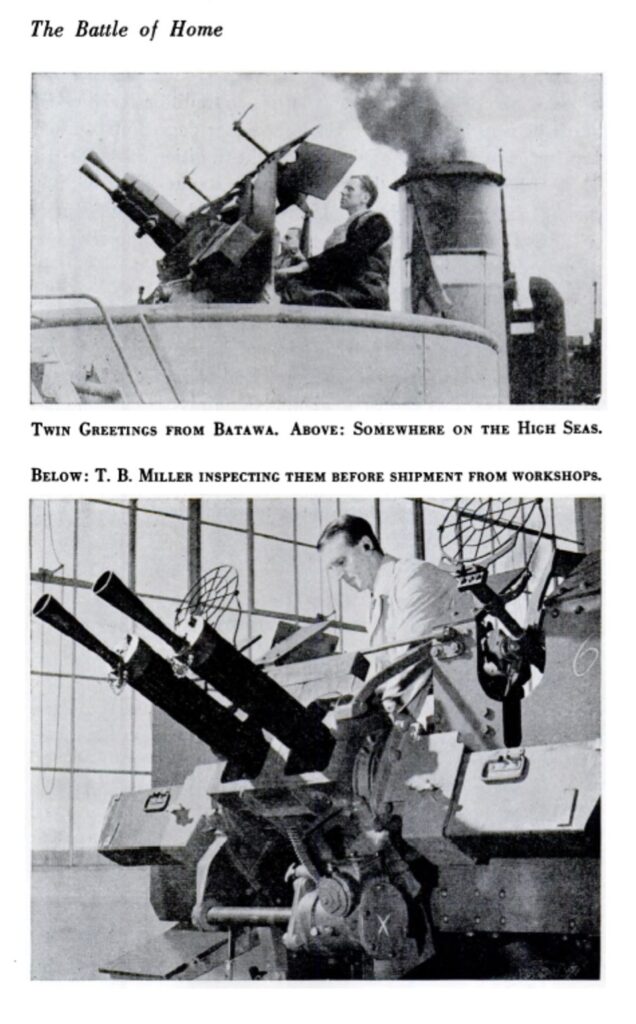

One reason only few shoes were produced, of course, was that the company had to adjust to the market “in a country gearing itself for war production.”16 And shoe production itself could not earn enough money to finance the construction of a new manufacturing site. In short: the “Miracle of Batawa,” which Canadian journalists were proclaiming as early as 1940, came with some limitations.17 Therefore, Thomas J. Bata offered his new production facilities and capacities to the Canadian government. Batawa workers then began production for the war, which Canada joined as early as 1939: “naval gun mountings, hydraulic components for aircraft, gyroscopes for torpedoes and primers for anti-tank shells, all produced in the newly organized workshops.”18

In this regard, Batawa became a space not of relocated knowledge of shoe production and its markets but of inadvertently “imported” Czechoslovakian labor. At the same time, it created new jobs in Canada. In 1944, about 1,000 mainly non-Czech workers were employed in Bata’s now Canadian company, mainly in Batawa; by 1946, this number had increased to 1,400.19

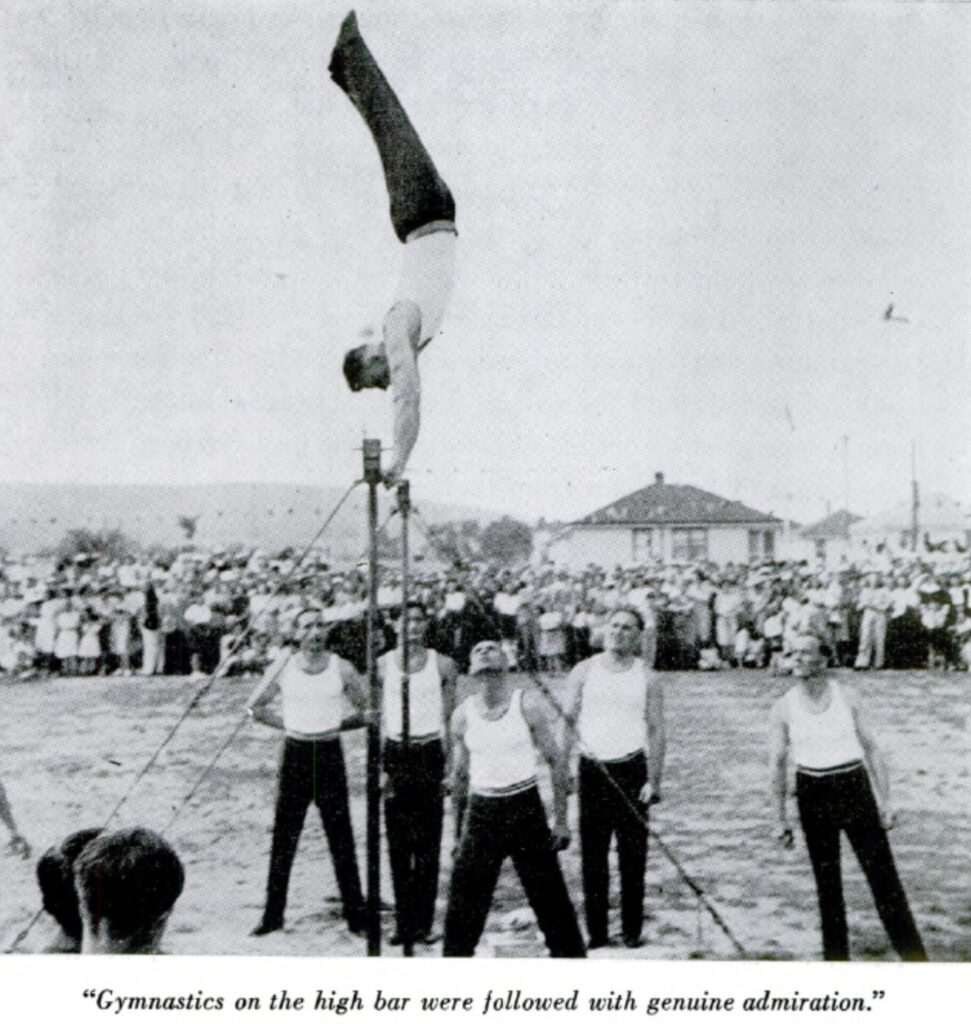

While knowledge transfers were not immediately important in this example, they did become important from an economic standpoint in the long run. This is because of the community concept Thomas J. Bata imported alongside the refugee-based production he launched. It was based on the strategies the company established already in the 1920s worldwide that created “ideal industrial towns” following Bata’s “ideological inspiration” that “workers produced not only shoes but their own modern body and biography.”20 Like these towns, Batawa’s infrastructure included housing, schools, groceries, an internationally known Sokol gymnastics organization, as well as a lending library.21

While the global company followed a decentralized management structure, Bata’s decision to focus beyond Europe proved successful: between 1946 and 1985, his company expanded to 80,000 workers, producing Bata shoes in 84 countries—organized from the headquarters of the company in Toronto.22

Just a Canadian Episode?

The Batawa example raises two questions from the perspective of migration and knowledge: First, what knowledge was lost? Such lost knowledge has received relatively little scholarly attention so far. Similar to many other examples in migration history, we do not know much about the coping strategies Batawa’s refugees utilized when they left Czechoslovakia, and the knowledge lost to their migration may have been substituted in the Czech factories that still existed.23 The second question is about the extent to which the Batawa migrants’ experience created bodies of knowledge beyond the translation or adaption of practical knowledge or specific skills.

The Batawa case—similar to other refugee stories—entails bodies of emotional knowledge, such as solidarity or empathy, that developed from their experience.24 We see this specifically in relation to the handful of Tibetan refugees Thomas J. Bata enabled to come to Batawa in October 1970. These three or four individuals were the first Tibetan refugees in Canada. Bata had visited India the year before and “witnessed the plight of the refugees first-hand.”25 Once again, Bata convinced the Canadian federal government to let them come. This example also stands for the long-term influence of experiential knowledge related to migration because it shows that Bata knew what the refugees needed to have orientation for the future upon their arrival. The Batawa community members had similar awareness deriving from their specific refugee experience: Hanns Skoutajan (1929–2015), for example, was ten years old when he came from Czechoslovakia to Batawa. After the Second World War, he studied at Queen’s University in Kingston and became actively involved in refugee relief—first for refugees fleeing Hungary in 1956, and as late as in the 1980s for refugees arriving in Canada from Southeast Asia.26

Both examples point not just to a transfer of knowledge but the translation of experiential knowledge into new political and socioeconomic settings—knowledge that was both local and global. Therefore, the Batawa refugees are an example of the complexity of knowledge transfers in relation to migration.27 This refugee group was able to enter Canada first and foremost because of the shoe-production knowledge the authorities anticipated would have a positive economic impact. While the same authorities rejected similar bodies of migrant knowledge in that same period and also in the following decades, it becomes clear that the Canadian case was strongly shaped by colonial ideas of racial and cultural superiority. Even so, Thomas J. Bata, like many other entrepreneurs, had already been active on global markets before migration. Based on his knowledge of regional and even local markets, of raw material supply, of style and fashion, in particular, and of class-related aspects like prices and even distribution, he developed specific strategies to adjust to international markets. His case thus exemplifies many of the constellations arising at the intersection of migration and knowledge.28 In fact, it was not just Thomas J. Bata who bore this knowledge: Hanns Skoutajan and others like him simply grew up in this refugee group and gained or formed experiential migrant knowledge before, during, and after migration.29

In this regard, this example is more than a Canadian episode because the Batawa story also reminds us to reflect much more on what the “transfer” or “translation” of knowledge meant to contemporaries30

Even though the manufacturing site did not survive into the twenty-first century, the community embodied and exemplified the ways various forms of knowledge have interacted with migration processes throughout history and points to what terms like knowledge transfer mean today within national or international migration and knowledge regimes or migrant knowledge networks and infrastructures similar to it.

Swen Steinberg is an adjunct assistant professor in the Department of History and the School of Religion at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and an affiliated scholar of the German Historical Institute Washington. His recent work focuses on the intersection of migration and knowledge as well as transit and unaccompanied minor refugees. He is a co-founder and co-editor of this blog and can be found on Bluesky under the handle “@swensteinberg.bsky.social.

- Anthony Cekota, The Stormy Years of an Extraordinary Enterprise … Bata 1932–1945 (Perth Amboy: Universum Sokol Publications, 1985), 156. ↩︎

- Gregor Feindt, “From Zlín to the World: Transfer, Emigration and Personal Agency of Jewish Employees of the Bat’a Shoe Company, 1938–1940,” Jahrbuch des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts/Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook 18 (2019 [2022]): 27–52, 115, 121–22; Frank Oxley, “What Came First?,” foreword of The Stormy Years by Cekota, 7, 9.↩︎

- Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933–1948 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012). Cf. also Marlen Epp, Refugees in Canada: A Brief History (Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association, 2017), 7–8; Ira Robinson, A History of Antisemitism in Canada: History and Interpretation (Waterloo: Wilfried Laurier University Press, 2015); Sharryn J. Aiken, “Of Gods and Monsters: National Security and Canadian Refugee Policy,” Revue québécoise de droit international 14, no. 1 (2001): 1–51.↩︎

- Cf. Emma Wyse, “‘What Frightful Children!’: The Disobedient and the Unruly in British Overseas Child Migration, 1939–45,” Journal of Contemporary History 60, no. 2 (2025): 235–53, special section “In Search of the Migrant Child – Entangled Histories of Childhood and Migration,” ed. Bettina Hitzer, Friederike Kind-Kovács, Swen Steinberg, and Sheer Ganor; Andrea Strutz, “Forced to Flee and Deemed Suspect: Tracing Life Stories of Interned Refugees in Canada During and After the Second World War,” in Internment Refugee Camps: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Gabriele Anderl, Linda Erker, and Christoph Reinprecht, 229–50 (Bielefeld: transcript, 2023); Patrick Farges, Bindestrich-Identitäten? Sudetendeutsche Sozialdemokraten und deutsche Juden als Exilanten in Kanada: Studie zu Akkulturationsprozessen nach 1933 (Bremen: edition lumière, 2015).↩︎

- Cekota, The Stormy Years, 161. See also Jennifer Evans, Swen Steinberg, David Clement, and Danielle Carron, “Settler Colonialism, Illiberal Memory, and German-Canadian Hate Networks in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries,” Central European History 56, no. 3 (2023): 1–22.↩︎

- Mark G. MacGowan, “Roman Catholics (Anglophone and Allophone),” in Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada, ed. Paul Bramadat and David Seljak, 49–100 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 68.↩︎

- Anthony Cekota, The Battle of Home: Some Problems of Industrial Community (Toronto: The MacMillian Company of Canada Limited, 1944), 40. Cf. also idem, Entrepreneur Extraordinary: The Biography of Thomas Baťa (Rome: Edizioni Internazionali Soziali, 1968).↩︎

- Cekota, The Battle of Home, 170, 199, and other examples on 42–45.↩︎

- See Lukas M. Verburgt, “The History of Knowledge and the Future History of Ignorance,” KNOW: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge 4, no. 1 (2020): 1–24.↩︎

- Cf. Martin Bemmann, “Ankommen dank Wissen: Erzwungene Migration, Wissen und die unwahrscheinliche Karriere Leon J. Koerners (1892–1972) in British Columbia,“ in Heimaten: Räume kultureller Politikgeschichte, ed. Florian Greiner and David Motadel, 189–206 (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2025).↩︎

- Feindt, “From Zlín to the World,” 115, 121.↩︎

- Cekota, The Stormy Years, 160.↩︎

- Cf. Epp, Refugees in Canada, 7–8; Angus McLaren, “Stemming the Flood of Defective Aliens,” in The History of Immigration and Racism in Canada: Essential Readings, ed. Barrington Walker, 189–204 (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2008), 200.↩︎

- Cf. Cekota, The Stormy Years, 158–59, 161; idem, The Battle of Home, 21, 76–78, 95–100.↩︎

- Idem, The Stormy Years, 166–68; idem, The Battle of Home, 52–75; John Meisel, A Life of Learning and Other Pleasures: John Meisel’s Tale (South Frontenac: Wintergreen Studios Press, 2012), 85–102.↩︎

- Cekota, The Stormy Years, 168.↩︎

- “Flight of the Refugees: Miracle of Batawa: Czech Boots and Shoes Made in Canada,” The Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan), December 28, 1940: 15.↩︎

- Cekota, The Stormy Years, 174. See also idem, The Battle of Home, 92–94, 116–19, 151–63.↩︎

- Cf. Cekota, The Stormy Years, 183; Industrial Canada 47, no. 5 (1946): 119.↩︎

- Feindt, “From Zlín to the World,” 116.↩︎

- Cf. Cekota, The Stormy Years, 162, 173; idem, The Battle of Home, 120–33.↩︎

- Oxley, “What Came First?,” 9.↩︎

- On this perspective, see Philipp Strobl and Swen Steinberg, “How to Analyze the Gap: Lost Knowledge and Migration – An Introduction,” Journal of Migration History 11, no. 1 (2025): 1–17, special issue, “Lost Knowledge: Approaching Migrant Knowledge After Migration,” ed. idem.↩︎

- Cf. Françoise Waquet, Une histoire émotionnelle du savoir: XVIIe-XXIe siècle (Paris : CNRS Editions, 2019).↩︎

- Laura Madokoro, “A Decade of Change: Refugee Movements from the Global South,” in Canada and the Third World: Overlapping Histories, ed. Karen Dubinsky, Sean Mills, and Scott Rutherford, 217–45 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 217–45, 234. See also Jan Raska, “Humanitarian Gesture: Canada and the Tibetan Resettlement Program, 1971–5,” Canadian Historical Review, 97, no. 4 (2016): 546–75.↩︎

- See Honorary degree file 1986, Secretariat file, 1001.12-63-38, Queen’s University Archives; Hanns F. Skoutajan, Uprooted and Transplanted: A Sudeten Odyssey from Tragedy to Freedom, 1938–1958 (Owen Sound: The Ginger Press, 2000). For another autobiographical account of a Batawa-related refugee biography, see Meisel, A Life of Learning, 125–32; for the post-WWII context, see Jan Raska, Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada, 1945–1989 (Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2018), and for knowledge transfers with regard to the Hungarian refugees Swen Steinberg, “Knowledge in Flight? Hungarian Refugees, the Sopron Faculty of Forestry at UBC Vancouver and Central European Concepts of Sustainability in Transit,” in Environments of Exile: Nature, Refugees, and Representations, ed. idem and Helga Schreckenberger, 181–95 (Leiden: Brill, 2025).↩︎

- Cf. Simone Lässig and Swen Steinberg, “Knowledge on the Move: New Approaches toward a History of Migrant Knowledge,” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 43, no. 3 (2017): 313–46, special issue, “Knowledge and Migration,” ed. idem.↩︎

- Cf., for example, Jan Logemann, Engineered to Sell: European Émigrés and the Making of Consumer Capitalism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2019).↩︎

- Cf. Lässig and Steinberg, “Knowledge on the Move.”↩︎

- Cf., for example, Philipp Strobl, A History of Displaced Knowledge: Austrian Refugees from National Socialism in Australia (Leiden: Brill, 2025); and idem and Susanne Korbel, Mediations through Exile: Cultural Translation and Knowledge Transfer on Alternative Routes of Escape from Nazi Terror (London: Routledge, 2021).↩︎