Editorial note: After five years, it seemed like a good time to reflect on the achievements and future goals of the blog. Our new blog content editor, Viola Alianov-Rautenberg—who will present her own research in an interview soon to be published on the blog—recently sat down with Migrant Knowledge cofounder Swen Steinberg to talk about the motivations for and founding of the blog, as well as its development and impact, including on his own research.

The Migrant Knowledge blog was founded five years ago. Can you tell us a bit about its creation? What led you and your cofounders to establish it?

The idea of systematically examining the relation between migration and knowledge predates the launch of the Migrant Knowledge blog in March 2019. Simone Lässig, as director of the German Historical Institute Washington (GHIW), harbored a strong interest in making this intersection a major research focus for the new GHIW Pacific Office on the North American West Coast at Berkeley, which she began building up in 2016. And this focus aligned closely with my own research interests. To define this research field, we successfully co-organized two panel series at the annual conferences of the German Studies Association in San Diego in 2016 and Atlanta in 2017 and co-edited special issues of Geschichte und Gesellschaft and KNOW: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge.

Then we started asking ourselves about the best way to disseminate cutting-edge research findings at the nexus of knowledge and migration. Since we wanted to make findings in this very promising field quickly accessible without any barriers, we felt that a traditional publication series would not be the best option. Rather, we wanted to give the field contours and momentum by helping scholars to network and to exchange ideas. This initiative proved successful in the long term as the five years of nearly 90 blog posts and over 150 individual and institutional network members demonstrate.

We drew inspiration for our plan from established academic blogs worldwide, notably benefiting from the experiences of the GHIW’s History of Knowledge blog, launched in December 2016 (which recently moved to a new domain, by the way). Thus, the journey to founding the Migrant Knowledge blog was multifaceted. It began in a “virtual” manner, long before the arrival of Covid-19: Andrea Westermann at the GHI Washington’s Pacific Office in Berkeley, Mark Stoneman at the GHIW, and I in Kingston, Ontario, embarked on this collaborative venture online, never meeting in person during the initial years. This fact remains striking: the blog successfully spread knowledge across borders, even without physical migration. This collaborative spirit has persisted even as the composition of the team has changed over time. Several GHIW research fellows and GHIW deputy directors, including Sören Urbansky, Andreas Greiner, and Nino Vallen before you, have taken turns wearing the content editor mantle, while Casey Sutcliffe has become the managing editor of both this blog and the History of Knowledge blog, and current Pacific Office Deputy Director Isabel Richter has assumed a supervisory role. The rotation of research fellows and deputy directors perpetually brings fresh perspectives and ideas to the blog—like your idea of interviewing me for this piece!—and Casey and Isabel secure continuity.

Can you say a bit about the term “Migrant Knowledge”? How was it coined and in what context?

Our considerations about the name for this new field stemmed from two key observations. First, we noted that historical migration research had shown little interest in the knowledge possessed by migrants. Perhaps this was, in many cases, due to accessibility to sources: state records documenting state-held knowledge about migrants, for example, are more readily available than sources detailing the individual lives of migrants themselves. Second, we discerned a tendency for scholars to focus narrowly on certain types of knowledge related to migration—particularly intellectual or scientific knowledge—to the exclusion of other types. This bias, too, was likely influenced by the availability and accessibility of sources.

Therefore, our starting point was the consideration that knowledge and migration are related to each other in myriad ways: there has always been knowledge about migrants in statistics; there has been knowledge for migrants in schools or programs aimed at their “integration',” but, above all, there has also been the knowledge possessed by the migrants themselves. From the outset, our approach centered on this last type of knowledge and on the migrants themselves as active agents in processes of knowledge production, transfer, translation, and adaptation—roles that remain significant even today. Migrants have consistently navigated challenges related to the knowledge they bring with them—it is often lost in translation or rejected and devalued by the receiving society. Concerning migration, we intentionally avoided limiting the blog to specific forms of migration, such as forced displacement, opting instead to include contributions on any form of mobility, and, at the same time, we opted to utilize a broad (and, therefore, highly inclusive) conception of knowledge. Our focus on migrants and the knowledge they possess revealed that migrant knowledge is transmitted, acquired, and modified in diverse contexts and shaped significantly by factors like class, gender, age, race, and language. In exploring the intersection of migration and knowledge, our primary interest has thus been in everyday knowledge, practical knowledge, and the knowledge produced during migration. After five years, I think the promise we saw in the field has borne fruit—recall that we have nearly 90 posts!—and there is still much to explore at this intersection of historical migration studies and the history of knowledge.

Do you utilize this concept in your research, and, if yes, how?

The intersection of knowledge and migration has been a central focus of my research for many years. My particular interest lies in the environmental knowledge migrants possess or acquire through their travels and how it is transformed in the process of their mobility. Specifically, I explore this dynamic through the lens of transatlantic exchanges in forestry and mining during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. My research delves into practices brought from one context and adapted in another. Our “Migrant Knowledge” perspective enables me to call the notion of straightforward knowledge transfer into question as it is particularly evident in fields like forestry that many concepts, such as those related to tree species, management strategies, or soil conditions, cannot simply be transposed to a new setting without significant modifications. Another area of my research concerns the processes of knowledge translation during transitional phases of migration when migrants’ lives are characterized by uncertainty and they often seem deprived of agency. Yet, in the international working group “In Global Transit,” which I also helped to found in 2018, we identified that, with a more nuanced lens, one can see that even in these phases of uncertainty migrants demonstrate various forms of agency. Additionally, I have dedicated years to investigating the role of age in the migration and knowledge context, especially challenging the perception that migrant children are largely passive.

Since 2020, the GHIW’s “In Search of the Migrant Child” international standing working group has systematically explored these overlooked spaces of knowledge translation regarding age, traditional knowledge-related roles in families, and gender.

I have focused particularly on the strategies young migrants, such as unaccompanied minor refugees in the 1930s and 1940s, employed to acquire knowledge. Without this expanded perspective beyond the immediate migration circumstances of such mobile groups, these critical knowledge-related processes would have remained invisible and unanalyzed. Similarly, if one fails to take these specific perspectives into account, one risks overlooking both the experiences of these migrants and broader trends in historical migration studies.

If you think about the beginning of the blog, what topics were most dominant then? Has this changed? How do you perceive the thematic development of the blog over the past five years?

I am uncertain if we ever truly had dominant themes across our blog’s now 88 feature posts. Ultimately, the content has always been shaped by the research interests of our contributors, whom we encounter in our own networks. Environmental topics, forced migration, age, and transit have certainly been prevalent, yet they have never been conceived in ways that excluded other topics. I believe this thematic openness allows for various conceptions of migration and knowledge and the intersection of the two, which, as I laid out above, has been a cornerstone of our blog’s identity.

However, I’d like to highlight something I consider central to the Migrant Knowledge blog: the majority of our posts are authored by scholars from the field of historical migration research. For this community, our blog has truly served as an invitation to reconsider their research through the lens of knowledge. In my view, this approach has been highly productive. Rather than identifying with specific trends, I see our blog as contributing to a fresh perspective, gleaning new insights into processes that have been researched before.

Can you talk a bit about the impact of the blog (e.g., networks, publications, conferences?)

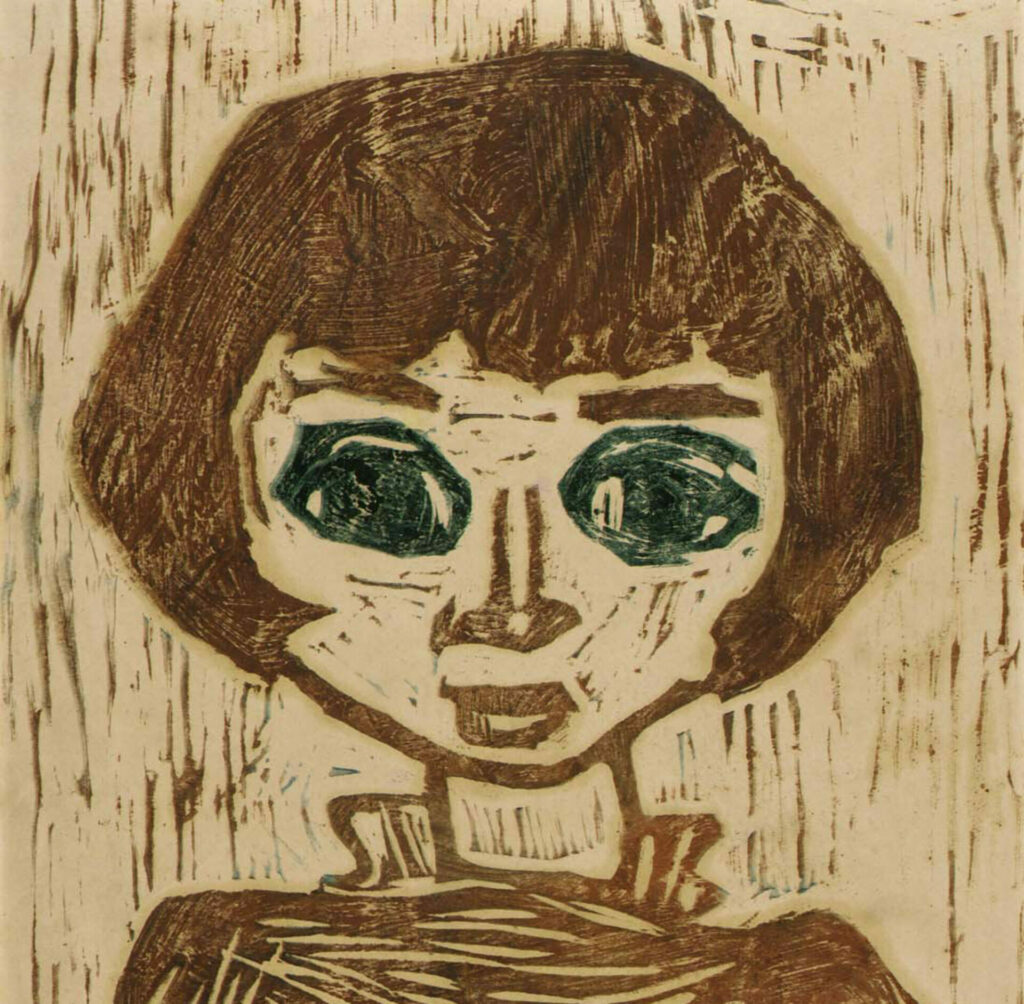

Assessing the actual “impact” of any research findings or publications is always a challenging endeavor as it is difficult to quantify or definitively gauge. From my perspective, the sheer number of contributions on our Migrant Knowledge blog speaks volumes: it is evidently highly visible and seems especially appealing to early career researchers. Moreover, the international network that has formed through our blog has successfully brought numerous scholars into contact with one another, fostering collaborations and vibrant academic discourse. Notably, platforms like GHIW conferences have repeatedly spotlighted discussions at the intersection of knowledge and migration. What stands out for me, however, are two miniseries we recently published on the blog that combine the idea of “Migrant Knowledge” with teaching: organized by professors, the contributions were written by students who discussed knowledge and migration in seminars in Germany and the US and then used our blog to share their findings with others. In this respect, the blog has begun to shape perceptions about migrants and their knowledge more generally and influenced the views of many scholars worldwide. The header images for these series are pictured below.

In my view, the most significant “impact” of Migrant Knowledge is that it initiated an international dialogue that continues to enrich our understanding of the intersection of migration and knowledge in history. At the same time, this conversation provides valuable insights into how we engage with migrant knowledge in contemporary contexts, offering ongoing opportunities for learning and growth. We saw this in collaborative projects such as the current Leo Baeck Institute Year Book (which is about to be published), which deals with transit in migration processes. Numerous early career scholars have told us that our Migrant Knowledge network and the working groups, workshops, and publications that have grown out of it have been very important for their careers and their establishment in the field. I think these growing structures show that the Migrant Knowledge blog is a project that continues to grow from within. All in all, the journey of the Migrant Knowledge blog is worth knowing about.

Thank you!!

Viola Alianov-Rautenberg joined the GHI Pacific Office as a Research Fellow in 2024. She is a historian of German, Jewish, and Israeli history of the 19th and 20th century. Her book, No Longer Ladies and Gentlemen: Gender and the German-Jewish Migration to Mandatory Palestine, was published by Stanford University Press in October 2023. Her current research project explores songs and singing in Jewish migration.

Swen Steinberg is an Affiliated Scholar at the GHI Washington. Currently, he teaches as an assistant professor in the Department of History and the School of Religion at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. His interests are located at the intersection of migration and knowledge, borderland networks, the history of social ideas, transit situations in migration, and refugees from Nazi Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe (especially unaccompanied minors).