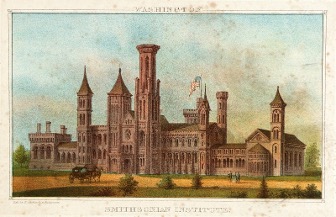

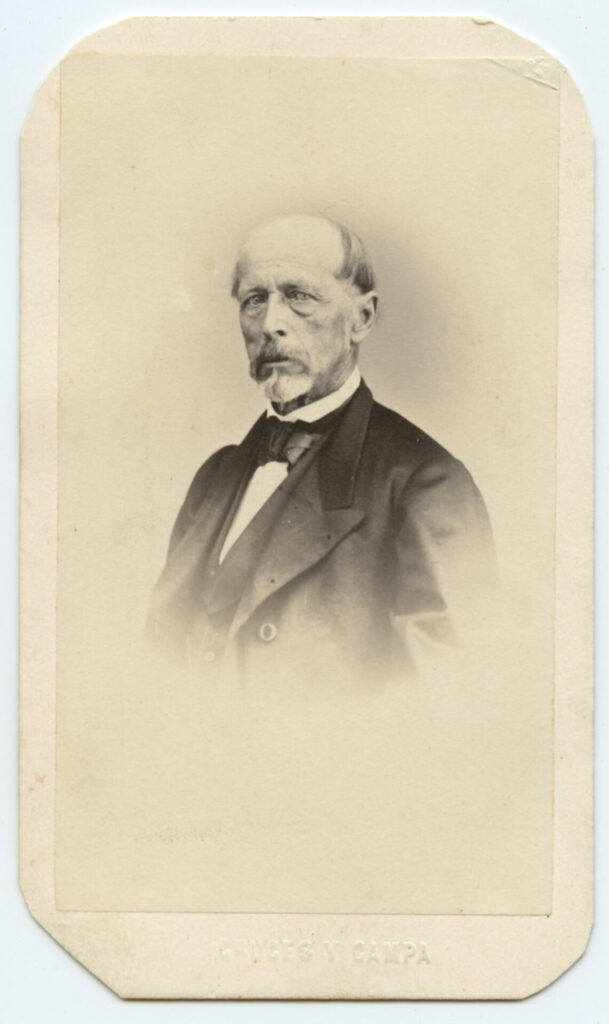

In July 1872, the Botanische Zeitung, a leading botanical journal in the German-speaking world, published an obituary for Carl Sartorius. According to this obituary, Sartorius – who had passed away a few months earlier at his settlement Hacienda Mirador – was one of the most prominent members of Mexico’s German diaspora. Even more important, the obituary continued, was the role Sartorius played in advancing natural science in Mexico. Despite the peripheral position of Hacienda Mirador, Sartorius had turned it into a center of scientific research that had succeeded in attracting the attention of several renowned botanists. The obituary went on to say that Sartorius had also gained a reputation as an avid collector of specimens that he sent to research institutions in Europe and the United States, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington being one of his most prominent recipients. The obituary quoted Sartorius describing his understanding of his scientific contribution from a letter he had written a few years earlier:

In all this time I have never ceased to be a Handlanger der Wissenschaft [assistant to science], that is, I have supplied material because I have always considered it a great folly to try to identify new findings here without the help of a large library and knowledgeable experts.1

In this article, I will explore the history of Mirador and the correspondence between Carl Sartorius and the Smithsonian as they reveal a hidden chapter in the history of German-speaking immigrants to the Americas and their role in producing knowledge. The article is based on an ongoing dissertation project that examines the intersection of German-speaking emigration, Mexican state-building, and science in the mid-nineteenth century. Though Mirador was a relatively small settlement, its history can show us at least two things: First, it shows the transformation of an originally utopian settlement into a prosperous plantation colony. Second, it demonstrates how a purportedly peripheral village became a major hub for scientific research in Mexico and the center of a transatlantic network for the exchange of knowledge and specimens. As I will argue, the history of Mirador is closely linked to the idea of a civilizing mission that both Mexican elites and European colonists shared. Within this mission, the taming of a perceived wilderness, the hunt for rare specimens, and ultimately also the collaboration with the Smithsonian played key roles.

From Utopian Settler to Amateur Scientist

Sartorius was born in 1796 near Darmstadt. After volunteering in the so-called Wars of Liberation against Napoleon, he studied theology and philology at the University of Giessen and started working as a teacher in 1818. During this time, he also became member of the so-called Gießener Schwarze, a radically nationalist and republican student association that sought liberal reforms such as basic civil rights and Germany’s national unification.

He eventually was arrested in the wake of the Carlsbad Decrees because of his contact with Carl Ludwig Sand, the murderer of August von Kotzebue. In 1820, Sartorius was suspended from his job and placed under police surveillance. To escape further prosecution, he decided to emigrate to Mexico in 1824. Upon arrival, he borrowed money from German-speaking merchants and bought a plot of land from Francisco de Arrillaga, a former Mexican finance minister who owned immense territories in the state of Veracruz.

Sartorius’s long-term project was to attract German emigrants and create a colony where he could realize the liberal dreams for which he had been forced to leave his homeland. Together with Karl Follen, a fellow student in Giessen and founding member of the Gießener Schwarze, he dreamed of establishing a utopian settlement on American soil where exiled patriots from Germany could find refuge and create a liberal model to counter the reactionary politics of the German Confederation. But this plan did not work out because none of the exiled demagogues was willing to come to Mexico. Follen, for instance, decided to move to Boston instead.

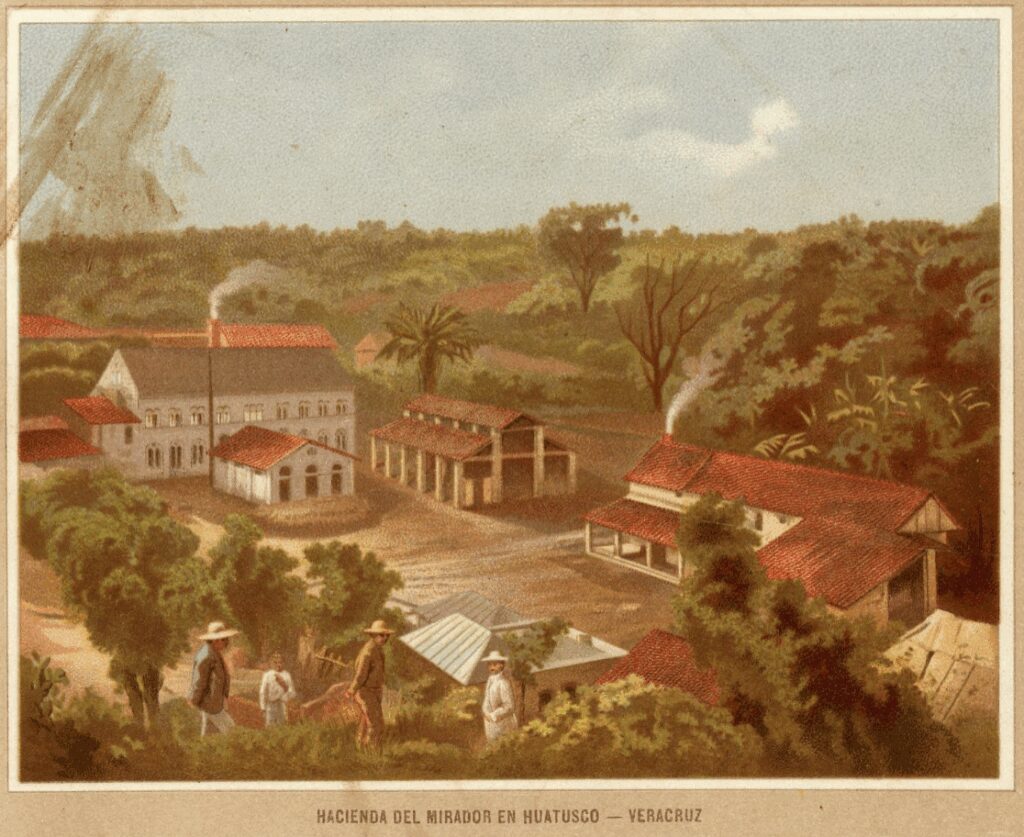

Sartorius therefore focused on building a plantation colony. Roughly twenty kilometers away from the town of Huatusco, his property was located between the Pico de Orizaba, Mexico’s highest peak, and the coastal hinterland of Veracruz. Due to the spectacular view one had from there, the plot was called Hacienda Mirador (with “Hacienda” meaning “estate” and “Mirador” meaning “lookout”). In the following years, Mirador developed into one of the largest sugar plantations in the state of Veracruz and one of the first haciendas in Mexico to use steam power for sugar production. At the same time, it became the largest German-speaking colony in Mexico outside the capital. By the mid-1830s, almost fifty foreigners resided in Mirador, as well as approximately 300 Indigenous day laborers.2

It is important to note that such a settlement project was in line with the goals of liberal Mexican politicians who deemed migrants from Europe necessary to increase the country’s productivity and harness its natural resources. Even more important for the government was the idea of “breeding” the local population, regarded as “uncivilized” by the country’s elites, with Europeans. The result of this experiment, Mexico’s ruling liberal class envisaged, would be a “refined” type of man that would increase the country’s level of civilization.3 This strategy, however, never materialized in Mirador, where local Mexicans lived separately from German-speaking colonists.

As Sartorius proudly wrote in 1835, his enterprise had transformed the area, which six years earlier had been nothing but jungle, into a commercial hub where all the “amenities of civilization” could be purchased. Also, Sartorius advertised his settlement as a place where colonists would not lose their “German character,” as they purportedly did in the United States. In his opinion, the “harder, more Nordic German character” in Mexico was not dominated by the “softer Hispanic-Indian character” but instead emerged “as the stronger” when the two groups interacted. In contrast, he claimed that in the United States, Germans were overwhelmed by the “sharply defined, speculative, practical character of the New Englander,” which caused them to lose their distinctive traits.4

Soon, however, Sartorius complained about trouble he had with many of the German colonists. Most of them were, he wrote, “clumsy and uncouth” and assumed they knew “everything better than the natives but made everything worse.” He explicitly mentioned that Mexicans were better qualified for plantation work than most of the German colonists. 5

Disappointed by the settlers’ behavior and attitudes, Sartorius shifted his focus from colonization to his growing sugar business in the late 1830s. Following in the footsteps of Alexander von Humboldt, he also began studying the natural environment around Mirador to make it accessible to European researchers. Already in the 1830s and 1840s, Sartorius had invited several European botanists and zoologists to his settlement, among them Frederik Liebmann from Denmark and Henri Galeotti from Belgium.6 The large and fertile estates of Mirador covering different climatic zones turned out to be the ideal territory for their collecting activities. Over the following years and decades, Mirador became a veritable fulcrum for scientific activities in Mexico. Similarly, although he was an amateur, Sartorius engaged in these collecting activities himself and became a correspondent for various scientific associations and institutions on both sides of the Atlantic.

Promoting the “Glorious Edifice of Science”

Undoubtedly, his collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution is the most prominent example of these connections. In the late 1850s, Joseph Henry, the Smithsonian’s secretary, sought to expand the network of amateur correspondents in North and Central America.7 In this context, Henry contacted Sartorius to request meteorological data about eastern Mexico. Sartorius responded that he could not provide exact data due to the poor quality of his barometer. Yet, he offered to send Henry the results of the observations he had made every day at 7 a.m., 2 p.m., and 8 p.m. in the previous years about the temperature, air pressure, humidity, and rainfall in Mirador. As he pointed out, he wished to support any kind of scientific progress and would thus be “pleased to send … every month a transcript of my daily threefold observations.”

Sartorius also mentioned that he was “well acquainted with the manner of collecting and preserving the different objects of natural history.” Promising a “rich contribution” to the Smithsonian, he announced he would send a “tin-box containing a little collection of bats …, one of the most unknown families of mammals and some exemplars of snakes, frogs and lizards, prepared in alcohol for Your collection.”8

This was the beginning of an intensive exchange between Sartorius and the Smithsonian that lasted until Sartorius’s death in 1872. In the following years, Sartorius expanded his collecting activities and became one of the Smithsonian’s main correspondents in Mexico.

As he explained in his German correspondence with Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian’s assistant secretary, the findings he made in the fields or in the forest were “purely accidental” given that he had to oversee “a property of 13 thousand acres,” where the plantations of “sugar cane, coffee, corn, cattle breeding and trade take up our activities and we can only devote the hours of leisure to science.” Sartorius added that despite his age – 65 in 1861 – he still spent four to six hours on horseback every day. Accompanied by his sons, hunting dogs, and rifles, he explained, “what we find en passant is shot and we have to prepare, conserve and pack it ourselves.”9

Among the items Sartorius collected for the Smithsonian were plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, and insects. Once he amassed enough specimens, he, together with his sons and local employees, taxidermied the mammals and birds and preserved animals such as reptiles and fishes in alcohol. In the mid-1860s, Sartorius also started to collect pre-Hispanic artifacts he found next to Aztec ruins on his property and wrote several field reports for the Smithsonian.

Although it seems as if Sartorius did all the collecting work himself, a careful reading of his letters reveals that he often relied on his local Indigenous employees for support. For instance, he mentioned that he expected them to watch for animals while they worked in the fields. Some of the workers were accidentally bitten by venomous snakes that Sartorius later taxidermied and sent to Washington. Additionally, when Sartorius encountered an unknown plant or animal, he often provided its Nahuatl name. Drawing on the existing Indigenous knowledge, he shared with Baird some characteristics of these specimens that his employees had explained to him; these later helped classify the species.10 Thus, Sartorius’s contributions were shaped by both his European training and the systematic incorporation of Indigenous knowledge from central Veracruz. Through his correspondence with the Smithsonian, this locally rooted expertise was absorbed into Western scientific classification, although the original contributors remained unnamed.

His correspondence with Baird also shows that Sartorius did not receive a financial reward for his work. Yet, he was compensated with scientific publications and his name being mentioned in the official documents of the Smithsonian. For instance, the institution’s 1862 annual report highlighted that it had worked with “Dr. Charles Sartorius, of Mirador,” a “highly valued meteorological correspondent” in the preceding years (interestingly, Sartorius was referred to as “Dr.” here even though he had never completed a doctoral thesis during his studies in Giessen). Further, the report noted the “gratification” for the institution in “aid[ing] him by identifying the species from his specimens, which his remoteness from large collections and libraries prevents him from doing for himself.”11 In fact, Sartorius agreed, arguing that “without a very complete library, which only large institutes can have it is ridiculous to try to determine for yourself, so I never try.” He was, therefore, grateful for any book he could receive from Baird or Henry.12

It seems that Sartorius’s main motivation for supporting the Smithsonian was his wish to contribute to scientific progress and to be part of the exclusive and transnational community pursuing that goal. As he explained to Baird in 1859, there was “a kind of freemasonry between the friends of the natural sciences throughout the world” where it was “necessary to promote the glorious edifice of science” and “everyone is glad to contribute material.” Even though the members of this community did not know one another, the common purpose of advancing science created “lasting sympathies” among them. Further, Sartorius highlighted his admiration for the United States in general and the Smithsonian in particular as new beacons of scientific research.13

Given his admiration of the development of the natural sciences in the United States, Sartorius was deeply concerned about the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. As he wrote a few weeks before the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, he still hoped the U.S. would find a peaceful solution that would preserve “the excellent institutes that have already brought so much light to the world” and fulfill the wishes of “all who have a heart for the progress of mankind.” As for the ongoing civil war in Mexico and the invasion of French troops in the early 1860s that paved the way for the Mexican Empire under Maximilian, Sartorius explained that he expected no improvement to the situation. “Politics,” he wrote, “is not my field, I am satisfied with observing nature, which offers compensation for the disharmonies of mankind.” 14

Conclusion

Indeed, studying and observing nature became Carl Sartorius’s main activity in his later years. As his private correspondence reveals, the erstwhile republican activist supported the rule of Emperor Maximilian between 1864 and 1867 because he saw it as an opportunity to advance the cause of science and civilization in Mexico. He not only hosted the emperor himself but also Austrian and French naturalists in Mirador who collected on behalf of Maximilian. In his self-declared role as a Handlanger der Wissenschaft, Sartorius maintained his scientific correspondence until a few days before his death and supplied research institutions in Europe and America – first and foremost, the Smithsonian, which has preserved a fascinating and little-known collection of specimens and artifacts from Mirador.

Andreas Markus Schurr is a PhD researcher in the Department of History at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. He is completing a dissertation project there on “Carl Sartorius, Hacienda Mirador, and the Conquest of Nature in Nineteenth-Century Mexico.”

- Botanische Zeitung, 5 July 1872, 509–10. This and all German quotations translated by the author. ↩︎

- On the early history of Hacienda Mirador and Sartorius’s emigration to Mexico, see Beatriz Scharrer, “Estudio de Caso: El Grupo Familiar de Empresarios Stein-Sartorius,” in Los Pioneros del Imperialismo alemán en México, ed. Brigida von Mentz et al. (Casa Chata, 1982); and Friedrich Wilhelm Weitershaus, “‘Wir ziehen nach Amerika’: Ein Beitrag zur Oberhessischen Auswanderung im 19. Jahrhundert,” Mitteilungen des Oberhessischen Geschichtsvereins Gießen, no. 63 (1978): 185–201. ↩︎

- Cf. Evelyne Sanchez-Guillermo, “Crear al hombre nuevo. Una visión crítica de los experimentos de europeización en Veracruz en el siglo XIX,” “América : identidades movidas – Dossier coordenado por Lea Geler y Evelyne Sanchez (accessed 25 July 2025); Moisés González Navarro, Los extranjeros en México y los mexicanos en el extranjero, 1821–1970, Vol. 1 (Colegio México, 1993), 10 and 29; and Charles A. Hale, Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora, 1821–1853 (Yale University Press, 1968), 215–47. ↩︎

- C. Sartorius, Mexico als Ziel für Deutsche Auswanderung (Reinhold von Auw, 1850), 66. ↩︎

- Enrique Silbermann, ed., Memoiren des Karl Christian Sartorius (Books on Demand, 2023), 322. ↩︎

- For an overview of the scientific travelers visiting Mirador up to 1850, see Carlos Ossenbach Sauter, Orquídeas y orquideología en América Central: 500 años de historia (Editorial Tecnológica de Costa Rica, 2016), 196–221. ↩︎

- Cf. Elizabeth Keeney, The Botanizers: Amateur Scientists in Nineteenth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 32–34. ↩︎

- Smithsonian Institution Archives (SIA) 000305 R010 Y1860 A0000152, 6 September 1859. ↩︎

- SIA 000305 R017 Y1863 A0000323, 26 May 1863. ↩︎

- See, e.g., SIA 000060 B06 F04 doc62, 13 December 1860, 24 July 1860, and 18 December 1860; see also SIA 000305 R013 Y1861 A0000053, 15 August and 25 October 1861. ↩︎

- Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, 1862), 54. ↩︎

- SIA 000305 R013 Y1861 A0000053, 4 June 1862.↩︎

- SIA 000305 R010 Y1860 A0000152, 10 November 1859; see also SIA000305 R016 Y1863 A0000183, 3 June 1863.↩︎

- SIA 000305 R013 Y1861 A0000053, 22 February 1861 and 4 June 1862.↩︎