In September 1791, an English traveler named Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim Simcoe embarked on a journey across the Atlantic, beginning what would become a five-year sojourn in the newly designated provinces of Upper and Lower Canada.1 From the day she left home, she kept an account of her travels, recording the temperature and weather; describing and depicting the landscape in words, maps, and drawings; identifying, sketching, and collecting the local flora and fauna; and remarking on the customs of the people she encountered. She did not collect most of this information with a view to publishing a travel account, or for the British government’s increasingly formalized geographic, natural history, or ethnographic collections. Instead, she sent these records, including installments of an ongoing travel diary, to family and friends in England. She directed them to a house in the Devonshire countryside, where they were pored over by four young girls and their caregivers, who also shared and discussed the information they learned with a wider network of friends and family.

Elizabeth Simcoe accompanied her husband John Graves Simcoe upon his appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. They also brought along their two youngest children. The Simcoes’ time in Canada was not meant to be permanent, but neither were they merely passing through on their travels. Their sojourn in Canada as part of the colonial government resembled what historians David Lambert and Alan Lester call “imperial careering,” a form of temporary migration.2 Like many Britons involved in imperial projects and colonial governance, the Simcoes and their children had a relatively high level of wealth, status, and education, factors which influenced their engagement with and understanding of the colonies, as well as the volume and survival of the record they left behind. The Simcoes also resembled many other families separated by their involvement in empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: their four eldest daughters remained in England at Wolford Lodge, the Simcoe family home in Devonshire, cared for by family friends.

Previous scholarship on Elizabeth Simcoe engages with her biography, her work as an artist, and her support of her husband’s formal colonial endeavors.3 By contrast, I consider her diary, letters, and artworks as artifacts from a wider transatlantic epistolary network. In light of scholarship on imperial travel writing, Simcoe’s output illuminates the ways that both she and her correspondents at home were also involved in the production and dissemination of knowledge about Britain’s North American colonies at the end of the eighteenth century.

Scholars of empire, migration, and family networks have demonstrated that letters and correspondence were central to maintaining and sustaining the relationships and connections of imperial families.4 Simcoe’s correspondents commented on how her letters had the power to bridge the geographic distance between them, especially when she provided them with accurate information and details about where she was situated. Questions of accuracy, observation, and representation are central themes in the scholarship on imperial travel writing, and although this work often focuses on accounts written for publication, unpublished letters and diaries can also provide useful commentaries about empire.5 These more informal accounts by travelers and migrants in colonial contexts often relied on similar techniques to published travel writing, with both using autobiographical details alongside firsthand experiences and observations in order to create a sense of authoritative knowing.6 To communicate as much information as possible about her travels and experiences, Simcoe used a range of descriptive and observational techniques that would have been familiar to her correspondents, given their varying degrees of familiarity with art, literature, travel writing, geography, zoology, botany, and ethnography. This was not a one-way process. The dialectical nature of the knowledge exchange and production is especially evident in the participants’ engagement with geography and mapping, as well as in their attempts to better understand the natural world.

Engaging with Maps and Geographic Knowledge

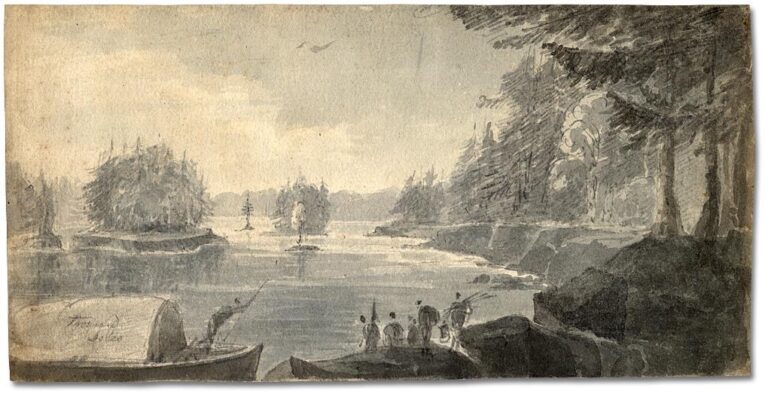

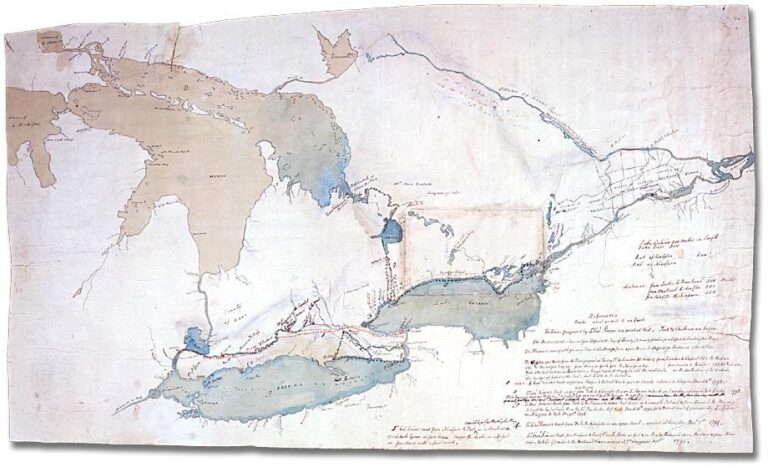

Elizabeth Simcoe and her correspondents took a keen interest in cartographic practices and in the geography of the places she saw. Art historian Denis Longchamps has explored her cartographic and artistic work in great detail, demonstrating that Simcoe used mapping techniques in her diary as well as in her sketches and maps, gathering information from others to represent places that she had not visited herself.7 In addition to sharing visual depictions, she also provided textual descriptions of Canada’s landscapes and geography.

Simcoe’s correspondents sometimes responded directly to the maps and descriptions she sent them, illustrating how those at home in England actively engaged with the geographical information they received. Her friends and family at Wolford and beyond often traced the journeys of the Simcoes and others on the maps that Elizabeth Simcoe provided, or on those they already owned. For example, in response to Simcoe’s lengthy description of the travels of a Mr. Littlehales, who had recently returned from Philadelphia, her friend Mary Anne Burges responded, “I shall look for Mr. Littlehales’s journey in all the maps I find when I go home; tho I believe I understand it very well already.”8 At other times, Burges expressed her frustration at not being able to find some of the places Simcoe mentioned with the resources at her disposal, as when she wrote, “I cannot find half of the islands you describe, which dissatisfies me extremely. I hope either Mrs Graves’s Books or my own will afford me some accurate map.”9

In addition to responding to her directly, Simcoe’s family and friends also discussed her maps, letters, and drawings among themselves. For example, Eliza Simcoe received a letter from her great-aunt Margaret Graves that discussed a packet that had recently arrived from Canada. It included a map drawn by Elizabeth Simcoe, and Graves wrote to Eliza that “your aunt Gwillim and I have been looking over it this morning and traversing the lakes and rivers which are in great abundance indeed, and surveying the different counties.”10 The Simcoe children also took a more active role in these cartographic practices, and Mary Anne Burges reported that their daughter Eliza was engaged in copying the maps that her mother had sent, and “is doing it very nicely indeed; and seems vastly pleased with an occupation which reminds her of you.”11 This testimony illustrates how those at home actively participated in the process of producing knowledge about Canada in order to understand a part of the empire that they would likely never visit.

Collecting and Categorizing the Natural World

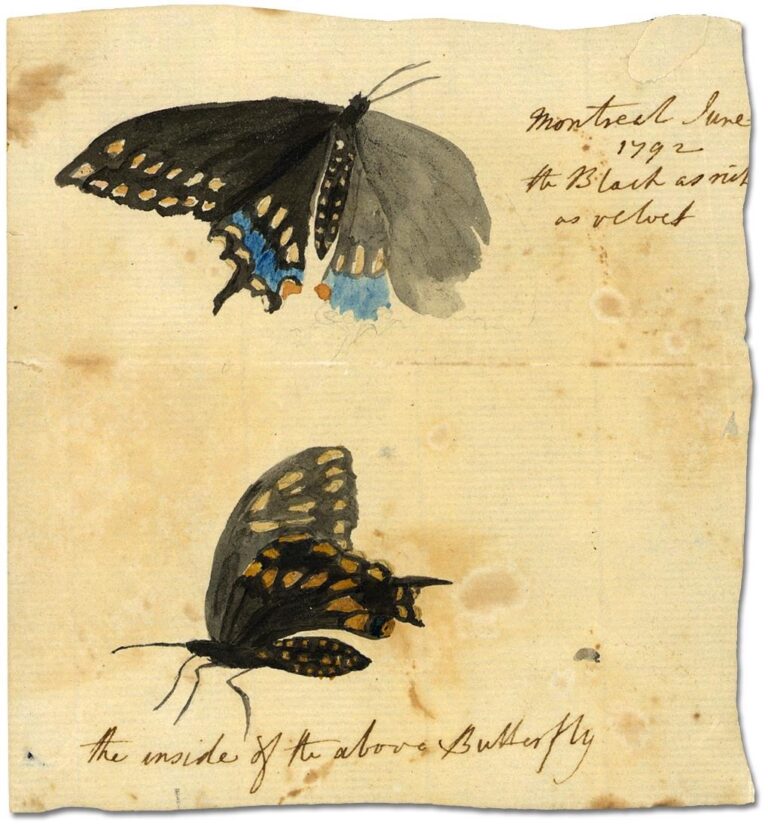

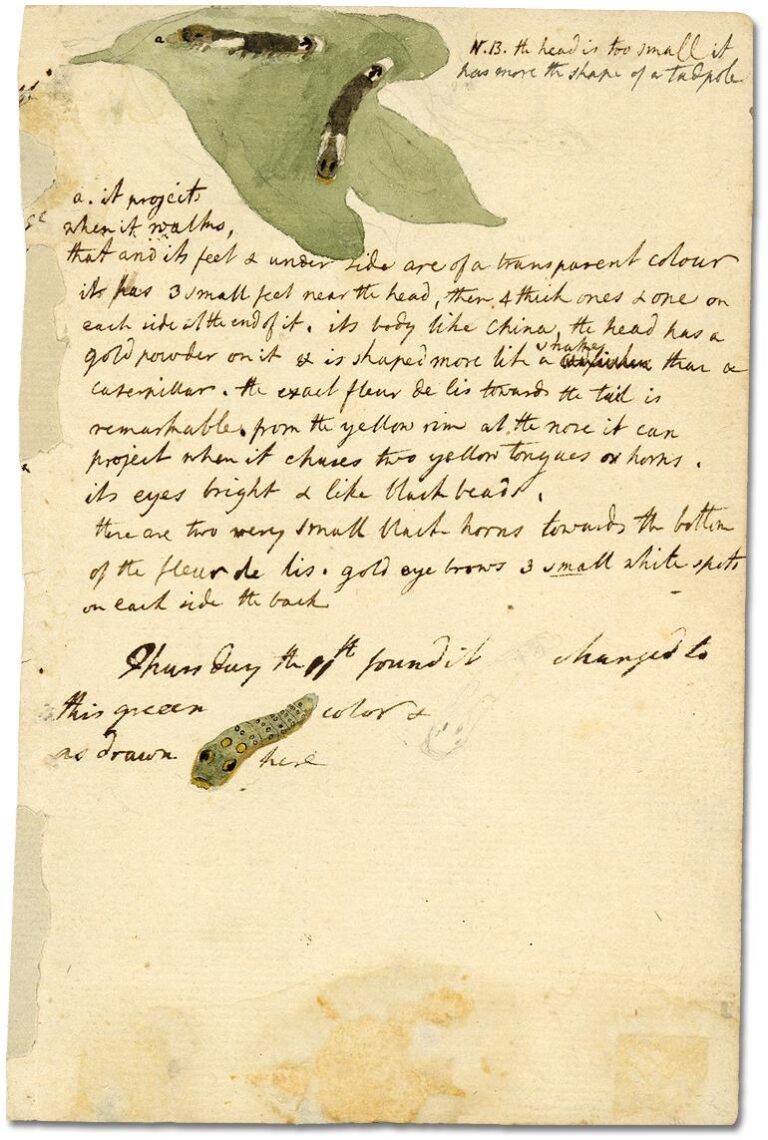

In addition to geographic information, Elizabeth Simcoe communicated a great deal about the natural world she encountered in Canada. Her accounts of flora and fauna sometimes relied on information reported by other people, and other times they were drawn from her own observations. Simcoe’s correspondents shared her interest in the natural world, especially Mary Anne Burges, who herself was involved in botanical and entomological networks in England. Simcoe was aware of Burges’ interests in general, including her particular interest in caterpillars, and incorporated details and sketches of them in her diary and correspondence. The language she used sometimes made it sound like she was also sending specimens back to England, as when she wrote “I send you a bat remarkable for its size & a beautiful black and yellow bird,” or “I am going to send you some beautiful Butterflies,” but it is likely that these were drawings rather than physical specimens.12

It is clearer that she sent actual specimens of plants along with her correspondence on some occasions, speaking to the interest in botany that she shared with those at Wolford. In a diary entry from September 1792, Simcoe wrote, “I send you May apple seeds,” and described the plant in great detail, including its physical appearance and size as well as the best conditions for its cultivation. 13 Whether in response to her sending these particular seeds or others, Mary Anne Burges responded, “I have left orders for the seeds to be sown immediately, and I am much obliged to you for them.”14

Simcoe was keen to accurately identify and name the plants she drew and collected. She also recorded their useful properties when she learned of them, for example, “the Cardinal flower which grows in the wettest & most shady places is a beautiful color. I am told the Indians use the roots medicinally.”15 Her plant identification often relied on local knowledge, as when she gathered a large number of plants on a visit to the home of her friend Adam Green, who gave her the names of all of them.16 The exchange of botanical information flowed not only from Canada to England. Mary Anne Burges occasionally looked up the plants that Simcoe described in the reference books in her library, or in those at Wolford. In July 1792, Burges wrote to Simcoe, “you cannot think how it has entertained me to look for your flowers in my different Books. Here follows the result of my enquiries.”17 She was able to find some of them and provided Simcoe with their Latin names and other details. There was one plant that she could not find any conclusive information about, but she promised to ask her wider network about it when she had the chance.18

Despite never having seen the sights of Canada in person, those who studied Elizabeth Simcoe’s diary, letters, drawings, and maps were able to engage with a wealth of information about Britain’s North American colonies from the comfort of their homes in England. This was not a one-way process, and information traveled both ways across the Atlantic, drawing on observational and descriptive techniques that were familiar to the correspondents from their knowledge of genres like travel writing, as well as other disciplines in both the arts and sciences.19 These examples highlight that in addition to more official channels, the intimate and personal networks of those who migrated to the colonies could also serve as conduits for knowledge about Britain’s empire in the late eighteenth century.

- The eighteenth century saw drastic changes in British territorial holdings in North America, such as the acquisition of formerly French territory in Canada at the end of the Seven Years War (including Quebec). Following the Constitutional Act in 1791, Quebec was divided into two parts, Upper and Lower Canada, each with their own governments. Upper Canada roughly encompassed the territory of the present-day province of Ontario, and Lower Canada of present-day Quebec. For the sake of brevity, and in line with its usage in much of the Simcoes’ correspondence, ‘Canada’ will be used here to refer to both Upper and Lower Canada. ↩︎

- David Lambert and Alan Lester, eds., “Introduction: Imperial Spaces, Imperial Subjects,” in Colonial Lives Across the British Empire: Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1–2. ↩︎

- For example: Mary Beacock Fryer, Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe, 1762–1850: A Biography (Toronto: Dundurn, 1989); Denis Longchamps, “Elizabeth Simcoe (1762–1850): Une amateure et intellectuelle anglaise dans les Canadas: Son oeuvre écrite et dessinée, et le projet colonial,” (PhD diss., Concordia University, 2009). ↩︎

- For a few examples of works that have informed this research, see Kate Smith, “Imperial Families: Women Writing Home in Georgian Britain,” Women’s History Review 24, no. 6 (2015): 843–860; Sarah M. S. Pearsall, Atlantic Families: Lives and Letters in the Later Eighteenth Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Laura Ishiguro, Nothing to Write Home About: British Family Correspondence and the Settler Colonial Everyday in British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019). ↩︎

- Gail Campbell, “New Brunswick Women Travellers and the British Connection, 1845–1905,” in Canada and the British World: Culture, Migration and Identity, ed. Philip Buckner and R. Douglas Francis (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006), 77. ↩︎

- Alison Blunt, Travel, Gender and Imperialism: Mary Kingsley in West Africa (New York: Guilford Press, 1994), 21.. ↩︎

- For much more on Elizabeth Simcoe’s art and cartography, see Longchamps, “Elizabeth Simcoe,” and Denis Longchamps, “Political Tourism: Elizabeth Simcoe’s Maps and Views of Canada (1791–1796),” Imago Mundi 66, no. 2 (2014): 213–23. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Simcoe, diary entry for January 1793, in Mrs Simcoe’s Diary, ed. Mary Quayle Innis (Toronto: Dundurn, 2007), 116; letter journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe, 1793, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), John Graves Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E (previously MG 23 HI1), ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc. 2, p. 432. ↩︎

- Letter journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe, 1791, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc. 2, p. 46. ↩︎

- Margaret Graves to Eliza Simcoe, December 20, 1793, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 31, doc. 6. ↩︎

- Letter journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe, 1793, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc. 2, p. 392. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Simcoe, diary entry for September 29, 1793, in Mrs Simcoe’s Diary, 142; Elizabeth Simcoe, diary entry for May 13, 1793, in Mrs Simcoe’s Diary, 129. ↩︎

- Undated sketch, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 26. ↩︎

- Letter Journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe from England, 1793, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc 2, p. 400. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Simcoe, diary entry for November 4, 1792, in Mrs Simcoe’s Diary, 113. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Simcoe, diary entry for June 12, 1796, in Mrs Simcoe’s Diary, 226–27. ↩︎

- Entry dated July 23, 1792, in letter journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc. 2, pp.197–98. ↩︎

- Entry dated July 23, 1792 in letter journal from Mary Anne Burges to Elizabeth Simcoe, LAC, Simcoe fonds, R5137-0-5-E, ser. 5, reel A-606, fol. 29, doc. 2, pp.197–98. ↩︎

- For more about Elizabeth Simcoe’s travels through Upper and Lower Canada with an emphasis on her artwork, see Travels with Elizabeth Simcoe at the Archives of Ontario. ↩︎