In the fall of 1948, dozens of Mexican men were recruited to pick cotton in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Their journey began in Gómez Palacio, a railroad hub in the northern Mexican state of Durango. The men traveled at their own expense, likely via train, to the growing metropolis of Monterrey, where they enlisted in the Bracero Program, the first major temporary labor recruitment or “guest worker” scheme jointly organized by the Mexican and U.S. governments. After screening and selection by representatives of both governments, they signed standard labor contracts with agents for the Farmers Association of Jefferson County, Arkansas. Many had some degree of literacy in Spanish and so could learn about the various guarantees that came with their contracts: set wage rates on par with local laborers, medical care, worker’s compensation, sanitary lodging (including blankets, beds, and mattresses), disability pay, and transportation to the work site with food along the journey.

Yet as soon as the recruiters’ trucks delivered them to their new work sites in Pine Bluff and Altheimer, Arkansas, the workers grew outraged at what they found. As two of the men, José Luís Landa and Manuel Gallegos, later declared, “In the field where we were staying and in the houses that were inhabited by blacks, in which there are no bathrooms … there are only beds without a mattress, and they gave us only one blanket. There is no electricity in the houses.” The men called upon the Mexican consul in San Antonio to come investigate. When consular officials arrived, all eight men who offered declarations denounced their own situations by referring to the South’s iconic oppressed labor force: “Our houses,” they protested, had been “abandoned by the blacks.”1

In my first book, Corazón de Dixie: Mexicanos in the U.S. South since 1910, I analyzed this story and others like it from the perspective of Southern, Mexican, and Mexican American social and labor history. Stories like this one, which illustrated the constant refusal of Mexican men in Arkansas to endure the conditions and segregation that African Americans faced, contrasted with other evidence showing the men actually preferred to socialize with blacks even once their legal access to white public space was secured.

Yet a different set of questions lingered for me after the book’s publication—questions at the intersection of social and intellectual history, albeit with a non-traditional cast of intellectuals at the helm. Mexico has had its own racial hierarchies to be sure, yet these bore only passing resemblance to the strict Jim Crow social and labor systems of postwar Arkansas. How, then, did Mexican workers know on their very first day in Arkansas that they must reject any treatment that placed them in the same category as black laborers? The historiography of Mexico shows how the Mexican state played a growing role in ordinary people’s lives from the 1930s to the 1960s. But how did these men know that a consular service existed in the United States, why did they believe they could make claims on this service, and what led them to expect that Mexican bureaucrats would actually pay their concerns heed?

My current projects probe the deepest intellectual roots and meanings of the Bracero Program by examining the history of ideas about migration and citizenship in the global twentieth century. I trace these ideas as they circulated among political leaders, bureaucrats, and migrants themselves. In an article in progress with Christoph Rass, we argue that a diverse mix of actors, including Mexican intellectuals and Mexican immigrant labor unions in the United States, helped spread the “guest worker” idea from Europe to the Americas in the interwar period. In particular, as early as 1920, Mexican migrants in Los Angeles learned about Italy’s work in bilateral labor migration treaties and emigrant protection. They then used this knowledge to broadcast their conviction that, as modern citizens, the guarantees of state protection were their best hope to resist labor exploitation in the United States. In my own monograph-in-progress, “Moving Citizens: Migrant Political Cultures in the Era of State Control,” I follow the story into the postwar years.

In the middle decades of the twentieth century, migrants confronted state-driven mandates to control labor migration and fashion it as a beacon of personal, family, or national modernization—or, as a betrayal of the nation. How did they respond?

I am digging deeply into the histories of migrations from Spain to France, from Malawi to South Africa, and from Mexico to the United States from World War II through 1975. I selected these migrations because each was well-established prior to the conclusion of bilateral agreements that ostensibly put sending and receiving states in the business of controlling migrant recruitment, screening, transport, labor, remittances, and return. Since well-developed transborder networks gave migrants multiple options, unsanctioned migrants outnumbered those who moved within official programs. Thus, rather than define my subjects as states did those who moved within official programs, I explore the worldviews of people in transnational communities comprised of both sanctioned and unsanctioned migrants.

Here I examine this dynamic in the cases of three laborers whose migrations used or evaded state-run migration programs from the 1940s to the 1960s: the Spaniard Joaquín C. in southern France, the Mexican Edmundo Mercado Canedo in Oregon, and the Malawian Samson King in Cape Town. I focus on moments when these men experienced illness or old age, and show how each utilized the resources of the states where they worked to defray the cost of their responses to that infirmity. In so doing, I argue that the practical knowledge about state bureaucracies that each man acquired at his work sites shaped, and was shaped by, multiple versions of citizenship that circulated in the postwar years, including those that emphasized social insurance, welfare capitalism, and classical liberalism.

Joaquín C. (French government archives require historians to conceal the personal details of private citizens) arrived in Aveyron, France, in August 1948 and went to work in agriculture. Spaniards comprised the overwhelming majority of foreign agricultural laborers in France from the late 1940s through the late 1970s, and local farmers were eager to employ him.2 Joaquín C.’s migration was nonetheless clandestine due to Spanish restrictions. Whereas French authorities sought labor migration recruitment agreements with countries such as Spain and Italy, which had long supplied workers, Francisco Franco refused to participate in such efforts during this period, arguing that his regime would put all hands to work at home. French authorities responded in 1948 by allowing immigrants who had crossed without authorization to sign work contracts and legalize their status once on French soil.3 A similar process known as “the drying out of the wetbacks” began on the Mexico–U.S. border that same year, when the two governments could not agree on the terms of bracero recruitment and protection.4 Despite Franco’s opposition to the departure of Spanish workers, hundreds of thousands of them were able to acquire medium-term work permits or refugee status in France, achieving varying degrees of freedom over where to work and live as well as access to the state’s generous social benefits. Joaquín C. was able to bring in his wife, who also hailed from a small town in Valencia, along with the couple’s two children, and a third child was born in France. French immigration, education, and social welfare policies in this period contained conflicting impulses regarding whether to treat immigrant workers as temporary and exploitable or instead as “future Frenchmen.”5 Spanish agricultural workers in rural southern France experienced both sides of this coin at different moments and in different aspects of their lives. Those who acquired refugee status, like Joaquín C., and accompanying family members were best positioned for long-term inclusion.

While the Spanish government in this period provided little to rural Spaniards like Joaquín C., the relative speed with which he gained access to the growing welfare state in France, including his children’s education in French public schools, quickly showed him the expanded role that a welfare state could play in his life. In 1954, at the age of 44, he fell ill and received treatment in government-run hospitals. Furthermore, after just six years in France, he already knew that his rights in times of illness went far beyond just medical care. He wrote to France’s Service Social d’Aide aux Émigrants (SSAE), a federally funded agency working to settle and integrate France’s foreigners, to plead for monetary assistance for his family so that his children could attend a summer camp. The family had already secured the assistance of a local government aid fund, the Caisse d’Allocation Familiar Agricole, but it still could not afford the camp on his wife’s wages as a housekeeper. Joaquín C. had learned that both local and federal welfare programs were willing to spend money on his children’s integration and would potentially increase their investment in his family in response to the financial setback of his illness.6 Rather than seek a return to Spain, the charity of the Catholic Church, or the solidarity of Communists or labor unions, Joaquín C. displayed a nascent investment in the French welfare state and its assimilationist assumptions. In this case, his children’s integration into summer camp also served the needs of his family by providing child care while he remained ill and his wife went to work.

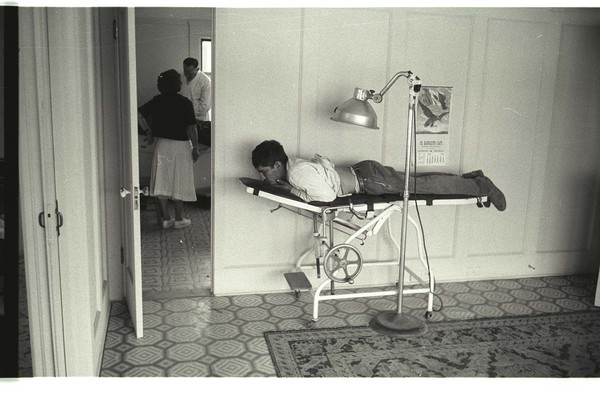

During the same period, a Mexican worker, Edmundo Mercado Canedo, confronted illness with more basic expectations: to receive medical care in the United States and the help of the state in securing his repatriation to Mexico. Mercado hailed from Morelia, the provincial capital of Michoacán. In 1943, he signed a bracero contract with the Southern Pacific Railroad to work near Corvallis, Oregon, and left his wife and child behind. When Mercado did not feel well, he utilized his rights as a bracero to visit the doctor, who diagnosed him with syphilis. The railroad engineer who supervised Mercado contacted the U.S. Employment Service’s (USES) War Manpower Commission’s District Manager in Portland and requested the worker’s repatriation to Mexico. The commissioner then journeyed to Corvallis and took Mercado’s declaration via an interpreter.

In the translated statement, Mercado Canedo said that he had been unable to work for multiple days that month due to his disease.

I have been examined twice by Southern Pacific doctors, who told me they can do nothing for my condition. I therefore request that I be returned to the point of recruitment in Mexico in accordance with the provisions of Section 24 of the individual work agreement, and that my contract of employment be cancelled.

The USES representative reminded the railroad that, under the bracero agreement, the cost of transportation and subsistence back to the point of recruitment was the employer’s responsibility.7 The obligation to cover this expense certainly would have irked Mercado’s supervisors. Since illness and injury were common due to braceros’ hazardous living and working conditions, the railroad typically did everything it could to keep workers on the job, but doctors had the final say as to whether an ill or injured man could return to work.8

In this case, Mercado felt sick, and his fatigue left him unable to earn the dollars for which he had come. Furthermore, he likely believed he would receive better medical care back home. His residence there, in downtown Morelia, was less than two miles from a state hospital. Moreover, standard treatments for syphilis existed at the time, though the doctor in Oregon did not offer them.9 Whereas the Spaniard Joaquín C. petitioned for direct state support for a broad range of expenses associated with his illness, Mercado utilized the provisions of his bracero contract, which established, at least in theory, a sort of migrant welfare capitalism holding employers responsible for financing migrants’ basic needs. Unlike his counterparts who joined the Bracero Program in the 1950s and 1960s, in 1943 Mercado Canedo would not yet have understood Mexican citizenship as a robust status conferring significant state support. War Manpower Commission records do not mention any attempt to involve the local Mexican consul. Similarly, without a nationalized healthcare system in Mexico or the United States at the time, Mercado understood the futility of petitioning for superior medical care in Oregon. His story illustrates how the bracero contract could combine with braceros’ actual experiences in the United States to introduce them to a form of citizenship that was mediated by employers.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Samson King was born sometime in the first decade of the twentieth century in colonial Nyasaland, which would become Malawi in 1964. A member of the Tonga ethnic group, he grew up in Nkhotakota (then Kota Kota), located in the central part of the country. Malawian workers had been migrating to Southern Rhodesia and South Africa since the late 1890s and, like their Mexican and Spanish counterparts, did so in increasing numbers during the interwar period. This is likely when King first arrived south of the Limpopo River. Since 1913, South African authorities had cited public health concerns in their ban on labor recruitment from so-called “tropical areas” north of 22 degrees south latitude, which included all of Nyasaland. But this ban was lifted in the mid-1930s, and the Nyasaland colonial authorities signed a labor recruitment convention in 1936 with South Africa’s Witwatersrand Native Labour Association.10 Meanwhile, black migrants like King, who had arrived in the country’s cities independently, found themselves in an ever more precarious position due to increasingly severe immigration and segregation laws.11

Even as authorities tightened their control over southern African migration and sought to channel it to mining and agricultural areas in the 1930s and 1940s, King maintained his life in Cape Town. As was typical for urban “Nyasas” of the time, he worked in a variety of service and office positions.12 He also fathered four children in South Africa. In 1952, South African officials informed King that he was a prohibited immigrant under the Immigration Regulation Act of 1913. Yet his employers at S.A. Advertising Contractors successfully petitioned authorities to continue renewing his six-month work permits. King was detained in 1955 after being convicted of the theft and possession of liquor, yet his new employer, the International Press Agency, successfully petitioned the government to renew his work permits. Finally, in 1959, the South African government asked King to produce tax receipts back to 1941, which he likely could not do. He was deported to Nyasaland with his wife and 14-year-old child Magdalena; his older three children had already married and so remained in South Africa. Presumably prompted by King’s employer, an immigration agent attached a handwritten addendum to the deportation order: “Always found him to be faithful, honest, and satisfactory to deal with.”13

If King (and, archival records show, other Malawian men like him) had used the influence of his employers to remain in South Africa despite his consistent excludability under ever-tightening immigration and apartheid laws and even a criminal conviction, why did his failure to produce tax receipts in 1959 become the obstacle he could not overcome? In all likelihood, it didn’t. While King’s birth date does not appear in his immigration file, available data demonstrates that he was at least 45 years old at the time of his deportation.14 He had already outlived the era’s life expectancy for Malawian men by nearly a decade.15 King’s immigration file refers to his expulsion as a “repatriation” and shows that neither he nor his employer fought it, suggesting that he allowed it to happen so that he could live his final years at home, free of constant scrutiny by the South African state and his urban employer. The journey home was long—at least 2,000 miles from Cape Town to Kota Kota—and the South African government committed 63 pounds, a significant sum, to King’s rail, bus, and food expenses.16

Malawian men who had come to South Africa in the interwar period, like King, tended to be mission-educated, and they engaged with a variety of intellectual currents, including Communism, trade unionism, pan-Africanism, nationalism, and a conception of British imperial citizenship tied to classical liberal ideals of free movement and equal treatment.17 Given King’s trajectory of increasing harassment by South African authorities, it was likely the latter value, namely, the right to work for a living under free and equal terms, that led him to assent to returning to Nyasaland. Though the South African state eschewed all responsibility for the health of black African workers who arrived outside of the bilateral labor recruitment scheme, King nonetheless saw this state as responsible for getting him home to live out his final days with greater freedom. The scholarship on state control over migration has focused on deportation in recent years, not only its bureaucratic mechanisms but also the role of deportability itself in disciplining immigrant labor.18 Less attention has been paid to the ways in which immigrants in specific situations could use deportation for their own purposes based on their knowledge of the immigration system.

Migrants in the Americas, Europe, and southern Africa all encountered the question of who would be responsible for meeting their needs in times of illness and infirmity. My early research shows how migrants in distinct situations, but all migrating in the shadow of increased state control, held receiving states and societies accountable to help them solve their problems, albeit in radically different ways. These states had pursued labor migration control to advance nationalistic goals. But in playing an expanded role in migrants’ lives, they also influenced migrants’ own views of what a state was and should do. They created openings for migrants to make claims, whether covert or overt, that drew on key postwar political ideas, including the French welfare state, U.S. mid-century welfare capitalism, and British classical liberalism.

Julie M. Weise is Associate Professor of History at the University of Oregon and author of Corazón de Dixie: Mexicanos in the U.S. South since 1910.

- Bracero declarations, October 1948, 1453/3, Archivo de la Embajada de México en los Estados Unidos de América (AEMEUA), Archivo Histórico de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Mexico City. ↩︎

- Ronald Hubscher, L’immigration Dans Les Campagnes Françaises: 19ème – 20ème Siècle, (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2005), 370–73. ↩︎

- José Babiano, “El Vínculo Del Trabajo: Los Emigrantes Españoles En La Francia De Los Treinta Gloriosos,” Migraciones y Exilios, no. 2 (2001): 16. ↩︎

- Deborah Cohen, “Caught in the Middle: The Mexican State’s Relationship with the United States and Its Own Citizen-Workers, 1942–1954,” Journal of American Ethnic History 20, no. 3 (2001): 116–18. ↩︎

- Tyler Edward Stovall, Transnational France: The Modern History of a Universal Nation (Boulder, Colorado: Routledge, 2015), 382. ↩︎

- SSAE dossiers individuels d’aide sociale aux migrants espagnols: Casanova-Cela, 19860309/97, Archives Nationales de France (ANF), Paris. ↩︎

- Correspondence regarding Edmundo Mercado Canedo, July 1943, War Manpower Commission, Region XII, Box 2967, Mexicans: Arvina-Ramirez, National Archives San Bruno (NA-SB), California. ↩︎

- Erasmo Gamboa, Bracero Railroaders: The Forgotten World War II Story of Mexican Workers in the U.S. West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016), 118. ↩︎

- Ricardo Espejel Cruz, “Breve Historia Del Hospital Civil De Morelia,” Espejel.com: Historia para la gente. ↩︎

- John McCracken, A History of Malawi: 1859–1966 (Rochester NY: Boydell & Brewer, 2012), 206–7. ↩︎

- Sally Peberdy and Jonathan Crush, “Rooted in Racism: The Origins of the Aliens Control Act,” in Beyond Control: Immigration and Human Rights in a Democratic South Africa, ed. Jonathan Crush (Cape Town: IDASA, 1998), 20–21; Henry Mitchell, “Independent Africans: Migration from Colonial Malawi to the Union of South Africa, c.1935-1961” (M.Sc. thesis, African Studies, University of Edinburgh, 2014). ↩︎

- Mitchell, “Independent Africans,” 39. ↩︎

- Black Labour/Foreign Blacks/Malawi/Samson King, 1945-59, 2/OBS, 3/1/710, Western Cape Archives and Records Service (KAB), Cape Town. ↩︎

- Black Labour/Foreign Blacks/Malawi/Samson King. ↩︎

- “Life Expectancy at Birth, Male (Years) – Malawi,” The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.MA.IN?locations=MW&view=chart. ↩︎

- Black Labour/Foreign Blacks/Malawi/Samson King. ↩︎

- Mitchell, “Independent Africans”; Henry Dee, “Central African Immigrants, Imperial Citizenship and the Politics of Free Movement in Interwar South Africa, c.1918–1939,” Journal of Southern African Studies, online December 6, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2020.1689005; Anusa Daimon, “‘Ringleaders and Troublemakers’: Malawian (Nyasa) Migrants and Transnational Labor Movements in Southern Africa, c.1910–1960,” Labor History 58, no. 5 (2017): 656–75, https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2017.1350537. ↩︎

- Cindy Hahamovitch, No Man’s Land: Jamaican Guestworkers in America and the Global History of Deportable Labor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); Nicholas de Genova and Nathalie Mae Peutz, The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2010). ↩︎