In her 1988 critique of white feminism titled Inessential Woman, Elizabeth Spelman described feminist knowledge production about women of color as “confusing imagining women with knowing them.”1 In today’s historical research, one example of a type that remains imagined and thus unknown is “the Turkish woman” in West Germany, that is, women who migrated to West Germany in the guestworker era of the 1960s.2 “The Turkish woman” is an almost mythical figure within West German history: she dominates large parts of the literature that, say, gynecologists and social workers produced on migrants in the late 1970s and 1980s. In this literature, migrant women from Turkey were characterized as “lost in the unknown,”3 as “backwards, isolated, needy,”4 and as absolute victims of their husbands and extended families, who exploit their care work and thwart their emancipation. Their prominent position in popular and scholarly knowledge makes them an interesting object of investigation.5 In this article, I look at the role migrant women play in this knowledge and ignorance production about “the Turkish woman.” Analyzing excerpts of an interview conducted as part of a larger research project on this same theme, I demonstrate how one woman utilized this knowledge to her own advantage, distinguishing herself from her peers and also exploiting ignorance about “the Turkish woman” when necessary.

Numerous critical research studies have been done to deconstruct “the Turkish woman.”6 What crystallizes in them is a discrepancy between the knowledge produced about Turkish migrant women and the multifaceted realities of their lives. These studies show how in the making of “the Turkish woman” in the 1970s and 1980s, specific issues were generalized into universal truths, such as her oppression under an orientalized patriarchy, her lack of education and language skills, or her tendency, rooted in archaic notions of a gendered division of labor, to stay away from the labor market. Meanwhile, other aspects of her reality were avoided or made irrelevant to this alleged knowledge. A more critical inquiry into these issues shows that much gets overlooked in these conceptualizations of “the Turkish woman.” For instance, when one generalizes a lack of language skills as a universal truth, one tends to miss that, between migrant women’s productive and reproductive labor, their capacity for formal language acquisition is limited, even when services are available and accessible at all; likewise, one minimizes their efforts to learn German informally and “get by.” At the same time, assuming such universal truths, one fails to critically reflect upon the politics of language as a marker of class and race.7 Following the approach of ignorance studies, I argue that this lack of insight into the lived realities of “the Turkish woman” cannot be reduced to people simply “not knowing”; rather, this ignorance is produced, cultivated, and structurally upheld.8

But to me, what is even more interesting than this produced knowledge and ignorance about “the Turkish woman” in West Germany is how the migrant women themselves have perceived and handled it. What strategies have they developed to cope with, resist, or harness this knowledge and ignorance?

To begin to answer this question, I conducted an interview with Funda.9 Funda migrated from Istanbul to a small town near Karlsruhe in the late 1980s. Much of the interview was about her occupation in two different nearby factories, the latter of which she had negative associations with, remembering a lack of connection with her Turkish colleagues and degrading treatment from her superiors. These recollections offer two areas for exploring expressions of knowledge and ignorance and how Funda dealt with them.

Reproducing Knowledge

Funda’s retelling of her relationship with her colleagues demonstrates how Turkish migrant women could themselves reproduce the disadvantageous knowledge produced about them in a way that was in their own interest. Funda’s colleagues were mainly other migrant women from Turkey whom she took great pains to distinguish herself from, as in this statement:

I couldn’t really get along with my own people, with the women there…. They are, how should I put it, “There is this sale going on; that furniture is cheaper”—that was what they talked about. “My mother-in-law is like that; this happened with my sister-in-law”—I don’t like to talk about that kind of stuff. ... They were a bit different, their glances were unsettling, everything about them was different.

Not only did she argue that she had nothing in common with her colleagues, making her choose not to engage with them, but she also distinguished her relationship with these colleagues from her relationship with another one, a migrant woman from former Yugoslavia, Vjola. Funda’s depiction of her friendship with Vjola, excerpted here, essentially reproduced images projected onto “the Turkish woman”:

During the break up of Yugoslavia, a Serbian woman came. Look, that was really interesting: what was done to us, they [my colleagues] did to her. What the Germans did to us with “don’t you understand?,” the way they act like you’re stupid while talking to you because you don’t speak the language—that’s what our women did to her. But I didn’t. ... We never separated, I’m always with her, not with the Turks. … We drink our water together, go to the bathroom together … She completed university in Yugoslavia, her husband too. She was an educated woman. So clean, decent. When you saw her coming to work, you wouldn’t believe it, she dressed better than office workers. She had her principles ... we were two organized and clean friends.

In an interesting process of differentiation, Funda portrayed herself and Vjola as a unit that “never separated,” with clear boundaries to the others. They did not mingle, she said, not only because the colleagues oppressed Vjola but also due to the many differences between them. When Funda described herself and Vjola as “educated,” “decent,” “dressed better than” others, having “principles,” and “organized and clean,” she was not necessarily directly characterizing the others. But, as she had previously emphasized that “everything about them was different,” her claims about herself and Vjola also function as claims about the others: whatever she and her friend were, the others were not.

This process is interesting not in that Funda othered her colleagues but in that she did it by deploying the existing knowledge about “the Turkish woman.” Funda utilized racial and class markers in the form of images of poverty, dysfunctional families, purity, literacy, and respectability to distance herself from her Turkish colleagues and cast herself and Vjola as different, more nuanced, not quite like Turkish women—in the same way the German migration system had othered her in producing knowledge about “the Turkish woman.” The example illustrates how Funda made this knowledge useful to herself by confirming it in relation to her colleagues while exempting herself from the characterization.

Using Ignorance

The next segment of Funda’s interview showcases a form of ignorance about “the Turkish woman” expressed by Funda’s superior, and how she approached it. Funda spoke at length about how violently he behaved due to the workers’ alleged lack of German:

Our Meister was really bad … He treated the women so poorly. ... He acted mean, for example, yelled at us. ... Among the Turkish women, he was good with the ones that spoke the language; with the ones that didn’t speak the language he spoke very roughly. ... “Go watch some German TV instead of watching Turkish,” he’d say…

In Funda’s view, he focused his rage on her because she knew the least German of all her colleagues. Later, she was moved to another department within the factory with different superiors, as she explained in the following exchange:

Funda: In the other department the younger superiors were really good. They cared about us, even if we didn’t understand them, they would explain. Actually, I did understand them, I just couldn’t find the words to answer. But with them, I did speak, with the words I knew, with that man, that superior, I did speak.10

Interviewer: So, would you act like you didn’t understand? Depending on how they treated you?

Funda: I don’t know how I decided that, but, look, with Hans [new superior] I spoke about everything, but with Günther [former superior]… —with that old idiot I didn’t want to, I would just say, “I don’t understand, I can’t speak German.” That’s all I would say. ...

Interviewer: But in your everyday life, when you went grocery shopping, for example?

Funda: I spoke, of course, I would say everything myself.

Interviewer: So you knew enough German to get through your day?

Funda: Yes, sure.

What form of ignorance was at play here? Günther displayed the presumption that the workers didn’t speak German and deliberately resisted learning it. Misunderstandings or inconveniences offered him opportunities to unleash his anger about this one problem he acknowledged. He ignored other possible reasons for disturbances in the workflow, or other possible explanations for their not speaking German other than laziness, nor could he perceive that the workers might actually speak German but were refusing to do so. He expressed an ignorance about migrant women’s individual realities and processes of German acquisition and turned their supposed lack of language skills against them to legitimate his abuse.

What interests me here is not whether these women spoke German or why they didn’t but the readiness with which the superior latched onto the language argument, a topic so extensively discussed with regard to “the Turkish woman” that not knowing German had become inscribed into her body, independent of any one individual’s unique circumstances. He showed an inability to recognize nuances in language skills or the lack of language learning opportunities: for him, “the Turkish woman” did not speak German—this knowledge (and ignorance) was a product of everything he didn’t (want to) know.

Funda’s response was to resist his demands and ignorance by embodying what he expected of her, denying communication, and, thus, sabotaging work. This tactic resonates with what Alison Bailey describes as “strategically acting in ways that conform to white expectations [as] clandestine ways of getting revenge for poor pay, [and] bad working conditions.”11 Funda did not explain or prove her ability to speak German; she did not see the need to fill in the deliberate blanks in his knowledge about “the Turkish woman” but instead acted in accordance with her boss’s assumptions to make work and life easier for herself.

Conclusion

Funda’s experiences as I have analyzed them here demonstrate how the framework of knowledge and ignorance pertains to everyday experiences of migrant women and that it can be useful to situate them as agents in the retellings of their own lives. Although Funda formulated creative responses to oppressive structures, we should not romanticize these moments of agency as they did not fundamentally shift the power dynamic. In reproducing classist and racist images of “the Turkish woman” for her own benefit and in denying her existent language skills to sabotage work, she found ways to deal with the system, but these strategies contributed to upholding rather than challenging it. Such everyday acts allowed migrant women to expand their options but did not help them achieve liberation. Rather, these acts functioned and continue to function as coping mechanisms for migrant women under oppressive systems even as the reality of their oppression within knowledge and ignorance production remains unchanged.

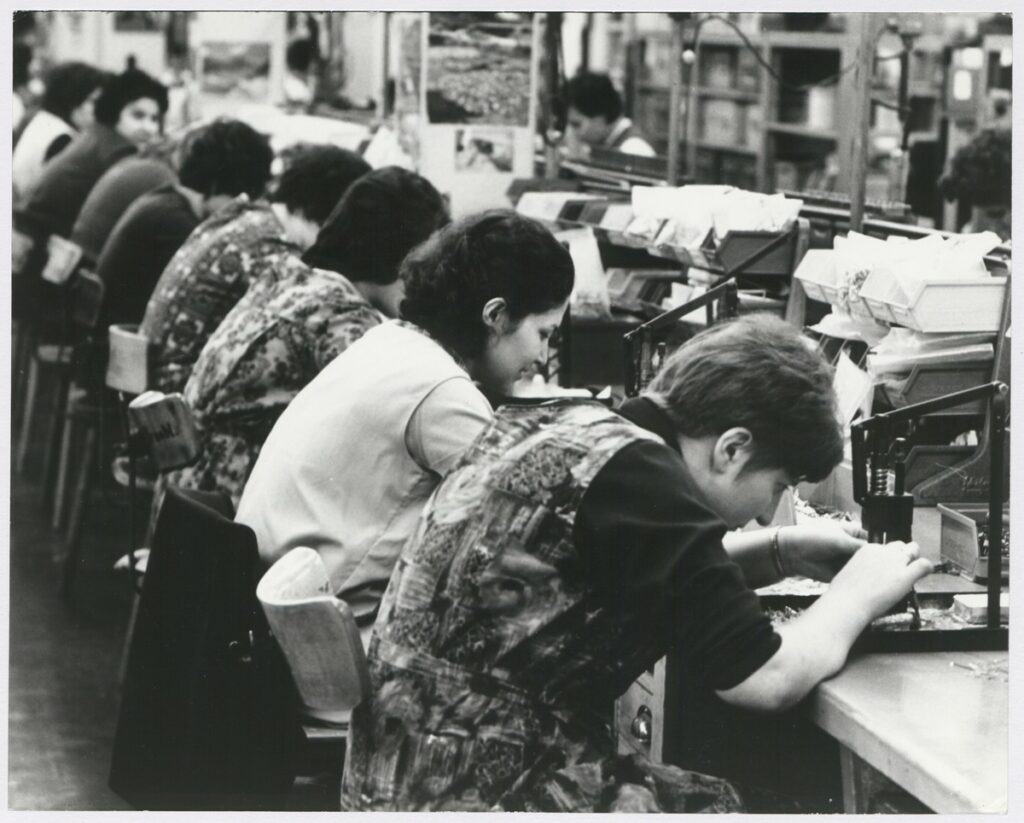

Featured photo used courtesy of ©bpk / Abisag Tüllmann (CC-Lizenz: BY-NC-ND). To download, please find the photo Arbeiterinnen bei Telefonbau und Normalzeit (T&N), Women working in telephone manufacturing, Frankfurt am Main, January 1969.

- Elizabeth Spelman, Inessential Woman: Problems of Exclusion in Feminist Thought (Boston: Beacon Press, 1988), 185. ↩︎

- To signify that I deal with the construct of “the Turkish woman” with all its projections on and assumptions about migrant women, I use the phrase in quotation marks. ↩︎

- Muradiye Cinar, “Verloren in der Fremde: Bericht einer türkischen Schülerin,” Courage 3, no. 4 (1981): 52. ↩︎

- Sabine Hebenstreit, “Rückständig, Isoliert, Hilfsbedürftig – Das Bild ausländischer Frauen in der deutschen Literatur,” Zeitschrift für Frauenforschung 4 (1984): 24. ↩︎

- On the dominance of “the Turkish woman” in the literature of this time, see Christine Huth-Hildebrandt, Das Bild der Migrantin (Frankfurt am Main: Bandes & Apsel, 2002), 53. ↩︎

- E.g., Yolanda Broyles-Gonzáles, “Türkische Frauen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Macht der Repräsentation,” Zeitschrift für Türkeistudien 1 (1990): 107–34; Gutiérrez Rodriguez, Encarnación. Intellektuelle Migrantinnen – Subjektivitäten im Zeitalter von Globalisierung: Eine postkoloniale dekonstruktive Analyse von Biographien im Spannungsverhältnis von Ethnisierung und Vergeschlechtlichung (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1999); Ulrike Lingen-Ali and Paul Mecheril, Geschlechterdiskurse in der Migrationsgesellschaft: Zu ‘Rückständigkeit’ und ‘Gefährlichkeit’ der Anderen (Bielefeld: transcript, 2020). ↩︎

- For more critical insights into the question of language and migration in the context of education, see Ince Dirim, “Sprachverhältnisse,” in Handbuch Migrationspädagogik, ed. Paul Mecheril, 311–25 (Weinheim: Beltz 2016). ↩︎

- For more on the implications of ignorance studies on German migration history, see Maria Alexopoulou, “Ignoring Racism in the History of the German Immigration Society: Some Reflections on Comparison as an Epistemic Practice,” Journal of Knowledge 10 (2021): 1–13. ↩︎

- F. A., interview by Kübra Göksel. July 24, 2020 (unpublished). All names were changed to protect the privacy of the interviewees. ↩︎

- Funda initially talks about multiple superiors in the new department but then focuses here on a single superior, whom she later identifies as Hans. ↩︎

- Alison Bailey, “Strategic Ignorance,” in Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, ed. Shannon Sullivan and Nancy Tuana (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), 88. ↩︎