In May 1920 Carl Düms, a German migrant in Mexico City, established the Servicio de prensa alemán en Latinoamérica (German press service in Latin America), better known as Agencia Duems, with the purpose of selling news stories regarding Germany to newspapers in Mexico, as well as Central and South America. Düms established the office of the press agency in the Casa Boker, one of the most important hardware stores, owned by the Bokers, a prominent German family that had resided in Mexico since the 1860s.

With his media enterprise Agencia Duems, Düms called for Germans in Mexico to support rebuilding Germany’s shattered reputation as a highly developed nation. Furthermore, Düms obtained subsidies and access to cable and telegraphic infrastructure from both the German and Mexican governments and, in return, committed to securing stable media relations between both countries and to offering reliable accounts of events in postrevolutionary Mexico and Weimar Germany. In 1922, Düms established an office in Berlin, run by his nephew Erich Düms, that sold news stories regarding Mexico in the German and Austrian press, published a few commemorative books and bulletins on Germany’s ties with Latin America and colonial relations with Africa, and exported books written in German to Latin America.

After Düms died in 1927, his nephews took charge of Agencia Duems in Berlin and Mexico City, but it ceased operations in 1932.2 During the agency’s existence, the Düms family became a relevant actor in Mexican-German relations and in the communications of German and Mexican governments with populations abroad. Carl Düms had thus laid the foundation for a family business that facilitated public diplomacy in a context in which the big news outlets and great powers were struggling to accept and cooperate with Weimar Germany and postrevolutionary Mexico.

Since Carl Düms was a migrant and a knowledge producer, my aim is to show how the connection of the history of migration and the history of knowledge can be useful for exploring the activities of Agencia Duems in Mexico and Germany from 1920 to 1932.3 More precisely, I aim to show the ways in which Agencia Duems, in collaboration with migrants, produced knowledge about Mexico, Germany, and Deutschtum (Germanness).

Producing Knowledge about Weimar Germany and Postrevolutionary Mexico

The information about Weimar Germany and postrevolutionary Mexico that Agencia Duems disseminated in newspapers contributed considerably to the construction and expansion of knowledge of Germany in Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas and knowledge of Mexico in German-speaking countries in Europe. In this way, Agencia Duems complemented knowledge generated by governments, academia, literature, mass media, and ordinary people.

Let us consider first the kinds of news stories Agencia Duems provided about Germany for Latin American readers. One topic was Germany’s domestic situation and the nation’s efforts to maintain political and economic stability. A second focus was the challenges Germany faced in the international arena. Two examples were the third uprising in Silesia (May–July 1921) and the occupation of the Ruhr (January 1923–August 1925), both of which were portrayed as risks for the stability of Germany and Europe. Germany’s role in multilateral spaces such as the League of Nations was a third type of news story, and Agencia Duems typically described Germany’s behavior as cooperative. The press agency also covered the domestic and foreign policy of European and Asian powers. News from Agencia Duems was published daily in local and national newspapers in Latin America.

The kinds of news stories the agency distributed to the German-speaking public similarly related to domestic and international politics in postrevolutionary Mexico, highlighting the government’s efforts to maintain stability in these arenas: Domestic political stories related to the delahuertista rebellion (December 1923–June 1924) and the religious conflict between the Mexican government and the Cristeros (August 1926–June 1929), for example. Foreign policy stories focused on Mexico’s relations with the United States and the United Kingdom, among other things. Agencia Duems also wrote news stories for the German press on Deutschtum in Mexico and other parts of Latin America, showing that German migrants had opportunities to engage in economic and cultural activities in the region. Unlike the German stories for Latin America, however, Agencia Duems’s stories about Latin America were only published very sporadically in Germany and Austria.

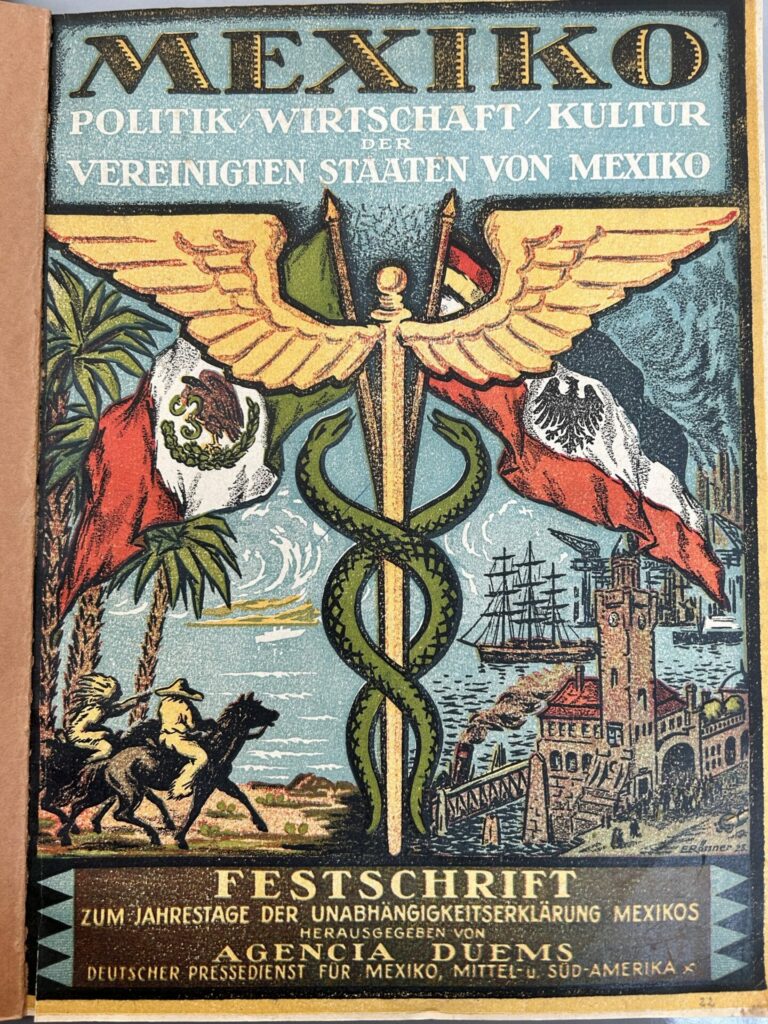

Furthermore, Agencia Duems published a few commemorative books and bulletins that contributed to the construction and expansion of knowledge regarding Germany’s international ties with Latin America and colonial relations with Africa. For example, in 1923 the office in Berlin published a 96-page commemorative bulletin called Mexiko. Politik / Wirtschaft / Kultur der Vereinigten Staaten von Mexiko in order to celebrate Mexico’s independence. It contained commemorative statements by Mexican and German politicians, diplomats, journalists, and businessmen applauding, alongside Mexico’s independence, the bilateral relationship. It also included articles on 1) Mexico’s political, economic, military, and educational situation after the Mexican Revolution; 2) the contributions of German scientists to understanding Mexico’s population, archaeology, and landscapes during the last decades; 3) the social and cultural spaces of Deutschtum in Mexico City; 4) the economic ties between Mexico and Germany; and 5) information about businesses that culturally connected Mexico and Germany. Most of the articles were written in German, some with translations into Spanish, and some included images of Mexico (emblematic buildings, archaeological findings, portraits, and landscapes) and tables of economic statistics.

Publishing Migrant Knowledge

Agencia Duems collaborated with Germans who were or had been migrants in Mexico to distribute knowledge about the country. In the 1923 Mexiko bulletin, two types of articles appeared: editorials by Agencia Duems with no named author, and those that included the name of authors. Most of the authors were Germans who were migrants in Mexico or had previously traveled or lived in Mexico. For example, the section “Wissenschaft und Kultur Mexikos,” which focused on Mexico’s population, pre-Hispanic cultures, and landscapes, appeared only in German and included the following articles:

• “Mexiko und Deutschland” on Mexican-German relations, written by German traveler, ethnologist and linguist Karl Sapper

• “Der Charakter des Mexikanischen und mittel-amerikanischen Volkes” describing the Mexican and Central American populations by Julio Jacquet, a German migrant who lived in Mexico City and was an active critic of the Weimar Republic

• “Aus Alt-Mexiko” focusing on the ancient Aztecs and Mayas by Baltic German traveler, colonial officer, and political publicist Paul Rohrbach

• “Tlachtli, das Ballspiel des Mexikanischen Kulturkreises,” which explained the findings around the ancient Maya ball game by German ethnologist, photographer, and writer Caecilie Seler-Sachs

• “Eduard Seler und Mexiko,” presenting a short biography of the German anthropologist, ethnohistorian, and linguist Eduard Seler with no named author

• “Die zeitliche Stellung der Tolteken” on the Toltecs written by the German ethnologist, linguist, and archaeologist Walter Lehmann, who at that time was the director of the research institute of the Museum für Völkerkunde

• “Mexiko und Zentralamerika,” which discussed the paintings of landscapes and different populations of Mexico and Central America by the German painter and author Max Vollmberg

• “Der Maler der zentralamerikanischen Tropen,” which offered a short biography of Vollmberg with no byline

• “Chapultepec, der einstige Kaiser- und heutige Präsidentensitz,” which explored the history of Chapultepec by H. Koehler

These articles included images (portraits, illustrations, and photographs). In 1923 Jacquet lived in Mexico City; Vollmberg lived and traveled between Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico; Sapper lived in Germany but had lived in and studied Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico in the last decade of the nineteenth century; Seler-Sachs lived in Germany but had made six expeditions with her husband Eduard Seler in Mexico and other parts of the Americas between 1887 and 1911; and Lehman also lived in Germany, but had traveled from Panama to Mexico between 1909 and 1911. Agencia Duems thus made use of knowledge from German writers, painters, and scholars who had experienced Mexico as migrants or travelers and had been involved in diverse activities. It is worth noting that Mexican diplomatic and consular representatives in Germany also offered materials (images, statistics, and articles) to Agencia Duems for the Mexiko publication; thus, Mexican migrants also helped build knowledge about Mexico.

Additionally, Agencia Duems disseminated knowledge based on migrant knowledge that could have been useful for people thinking about migrating to Mexico or other parts of Latin America. This was clear in the 1923 Mexiko commemorative bulletin that included the section “Das Deutschtum in Mexiko,” which focused on the activities of Germans in Mexico. The articles in this section were written by German migrants and only appeared in German. It included the following articles:

• “Die deutsche Schule zu Mexiko” regarding the history and current status of the German School in Mexico written by its director Traugott Boehme

• “Die deutsche Sprachschule in Mexiko” (anonymous author), which mentioned the cultural work done by the Academia de Alemán, especially its language courses teaching German to the general population and Spanish to German migrants

• “Das Liebeswerk des Deutschen Frauenvereins von Mexiko in und nach dem Kriege,” which mentioned the work done by the Association of German, Austrian, and Hungarian Women during the Great War to collect clothing for soldiers, and money for soldiers’ mothers, and after the war for Germans in Mexico and children in Germany, written by Cornelie Inversen

• “Der deutsche Ruderverein in Mexiko” (anonymous author), which highlighted the importance of the Association of German Rowing

• “Bund deutscher Frontkämpfer in Mexiko,” which mentioned the existence of the Union of German Combatants in Mexico (with more than fifty members) that had called for a French film vilifying German soldiers with comments against the German army in the Mexican press to be censored and supported collections for Germans in the Ruhr, written by C. G. Thewaldt

• “Der deutsche Turnverein in Mexiko” (anonymous author), which covered the existence and activities of the German Gymnastics Club in Mexico

The articles highlighted that these spaces with Germans in Mexico avoided discussions of political and religious topics. Moreover, newspapers in Germany published information that came from Agencia Duems regarding German migration in Latin America. For example, the Solinger Tageblatt published the article “Ein deutscher Kulturwerk in Chile” on the opening of a “German room” in the National Library of Chile (November 3, 1922) and the Kölnische Zeitung published the article “Deutsche Einfuhrhandel in Uruguay” on the role of Germans in the import sector in Uruguay (August 7, 1923).

Conclusion

The connection of the history of knowledge and the history of migration has helped me approach Agencia Duems not only as a useful actor that helped Weimar Germany and postrevolutionary Mexico communicate with foreign populations but also as a source of knowledge useful for the general public, political and economic circles, and migrants. The connection of these fields can facilitate the exploration of the ways in which the Düms family worked as a cultural translator between Mexico and Germany, and how the knowledge Agencia Duems produced was valid or relevant for readers in Spanish-speaking and German-speaking countries, among other questions.

Itzel Toledo García is a Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellow at the Latin American Institute of the Freie Universität Berlin. She specializes in the history of Mexico’s international relations from the 1870s to the 1930s. She currently explores the use of public diplomacy by Weimar Germany and postrevolutionary Mexico.

- In 1917, after spending some years in the United States, Carl Düms moved to Mexico City, where he established the news agency Servicio Atlas. He closed it in April 1920 because newspapers stopped buying his news due to his association with German imperialism and the German Legation’s decision to stop providing monthly subsidies. ↩︎

- Stefan Rinke, “Der letzte Freie Kontinent”: Deutsche Lateinamerikapolitik im Zeichen transnationaler Beziehungen, 1918-1933 (Stuttgart, 1996), 549-59. ↩︎

- On the connection of these fields, see Simone Lässig and Swen Steinberg, “Knowledge on the Move: New Approaches toward a History of Migrant Knowledge,” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 43 (2017): 313-46; Andrea Westermann, “Migrant Knowledge: An Entangled Object of Research,” Migrant Knowledge, March 14, 2019. ↩︎