The Cardenal Antonio Samoré international border crossing is more than just a border between Chile and Argentina.1 Located in the Andes, it lies on a mountain pass surrounded by dense forests, lakes, volcanoes, rivers, waterfalls, and a variety of native fauna. Day after day, this route connects hundreds of people between the two countries, specifically linking the cities of Villa La Angostura and San Carlos de Bariloche in Argentina with Osorno in Chile. On both sides of the border, there are state institutions that take care of customs and protections for agriculture, food, and sanitation.

During the formation of nation-states in Chile and Argentina, a period of extreme violence against Indigenous peoples began, characterized by military campaigns and traumatic events.2 By the late 19th century, governments consolidated territorial boundaries and regulated border crossings, severely affecting relations among Indigenous groups on both sides of the Andes. In response to these campaigns, euphemistically called the “Conquest of the Desert” in Argentina and the “Pacification of the Araucanía” in Chile, many Indigenous communities sought refuge by crossing the Andes.3 This process of border consolidation also imposed an internal frontier within Argentina, shaping a “white and homogeneous” nation identified with European pioneers that stood in stark contrast to Indigenous and Afro-descendant groups.4

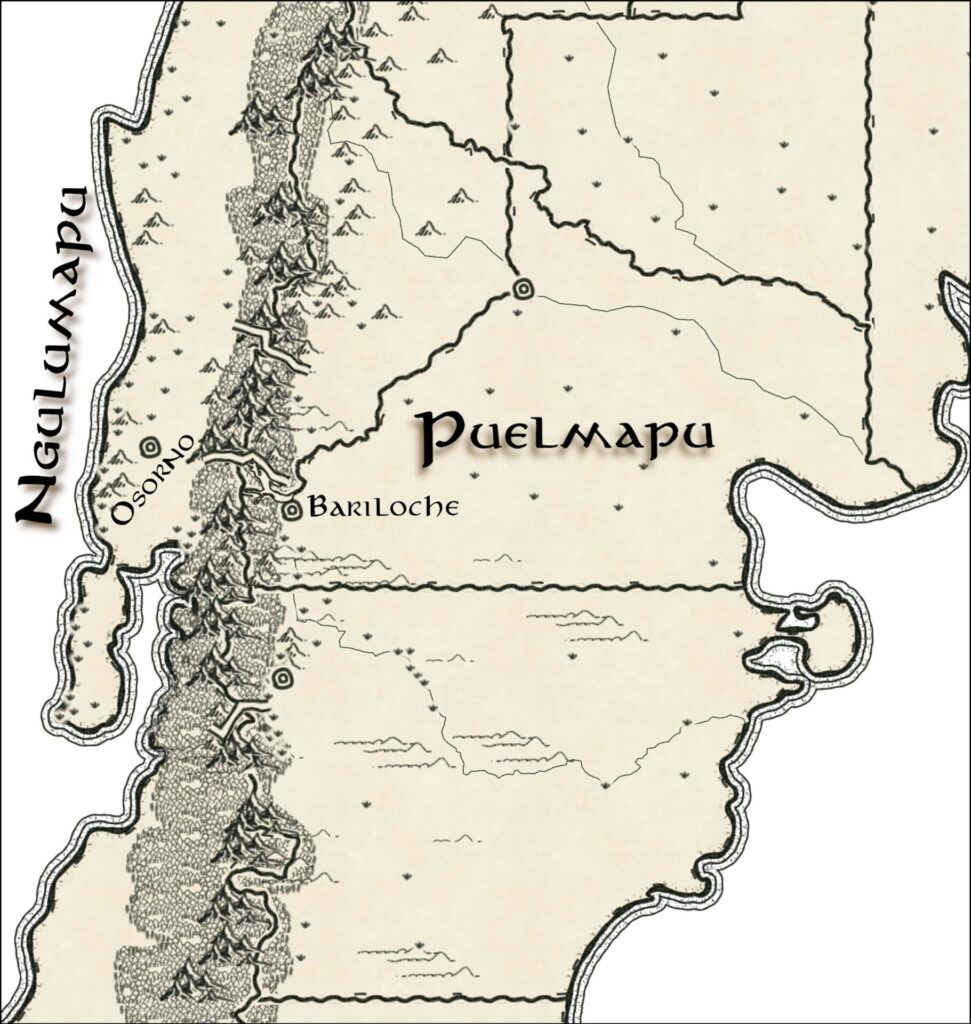

For Mapuche-Tehuelche people, this territory has a much older history, deeply marked by memory. In their language, Mapuzugun (the Mapuche language), they call the eastern part of the mountains (present-day Argentina) Puelmapu and the western side (present-day Chile) Gulumapu. They do not regard the mountain range as a barrier but as a shared and transited space, they inhabited freely before the dividing lines were drawn on maps. Oral accounts and historical records recall how the Mapuche-Tehuelche people traveled this vast territory without restrictions or borders. Even after tragic episodes such as the “Desert Campaigns” and the “Pacification of the Araucanía,” Indigenous memory persists, evoking a mountain range that has been space of life and mobility for centuries. In the elders’ “stories of before” from the end of the 19th century, the Mapuche territory is constantly recalled as a shared space “on both sides” of the current state borders.

Based on my undergraduate thesis,5 I am currently writing a doctoral dissertation in anthropology focused on the use of ancestral Mapuche medicine, which is known in Mapuzugun as lawen, and the associated memory processes. Since 2017, I have conducted fieldwork and in-depth interviews in various communities across Patagonia. This research on the collective memory concerning lawen has allowed me to trace connections to the migration and mobility of the Mapuche-Tehuelche people in the territory they have inhabited since ancient times. Within this framework, I conceive of the region as an open and connective space historically traversed by the Mapuche people.

In this blogpost, I first explore the memories that position the Andes Mountains as a space of transit. To do so, I draw on the work of anthropologist Ana Ramos, whose research on the oral and collective memory of the Mapuche people in Chubut, Argentina, demonstrates how they preserve and reinterpret the past in the present with political and affective significance. Secondly, I analyze specific issues related to the Cardenal Samoré border crossing, where the imposition of state borders6 reveals how collective memory takes center stage in contemporary struggles over territory, health, and knowledge.

Narratives of Memory and Mobility

Where the map cuts, the story crosses.7

The history of the Mapuche-Tehuelche people is deeply intertwined with memory. In the nineteenth century, many Mapuche families lived in the Andean foothills, where important discussions between community leaders (pu logko) strengthened alliances and relationships. Both oral memory and historical chronicles describe the Andes mountain range as an "open space" for movement, between what is now Chile and Argentina. The oral and collective memory of the Mapuche-Tehuelche people speaks of a time before state-imposed borders, highlighting the Andes as a space of transit and refuge during periods of military persecution.8 Families and individuals began pilgrimages in search of a place where they could "live in peace" and reconstitute themselves as lofche (communities). These people returned from the concentration camps to which they had been transferred or from the places in the mountain range where they had remained hidden from the armies. The Andes not only served as a place of transit but also as a space to forge relationships with spiritual forces (ngen, newen) that guided the survivors and strengthened their ties through Puelmapu and Gulumapu.9

From the 1890s to the 1930s, Mapuche-Tehuelche families returned to their territories, carrying with them stories of violence, loss, resilience and spiritual guidance. These experiences remain central to contemporary struggles over border crossings and territorial rights.

Contested Borders: The Struggles for the Defense of Lawen (Mapuche Medicine)

The Andes, as a “space of practice,”10 have deep significance in Mapuche collective memory as sites of mobility, action, and alliances. However, the imposition of state borders divided Mapuche-Tehuelche (Wallmapu) territory and disrupted cultural practices, including the use of lawen (mapuche medicine).

Comprising medicinal plants, herbs, roots, and natural elements, lawen is central to Mapuche health. However, state agencies such as SENASA (Argentina) and SAG (Chile) regulate border crossings, often confiscating these materials under phytosanitary regulations. This has led to ongoing conflict, with Mapuche communities advocating for the free circulation of their medicine across borders.

The defense of lawen transcends health; it challenges imposed borders and state policies that fragment ancestral territory. Following the military campaigns of the nineteenth century, spiritual leaders such as machi (healers) were persecuted, forcing many mapuche families to seek medical care in Chile, where the role of machi, although questioned by the Catholic Church, remained more visible.11

In recent decades, machi treatments have gained prominence. Families from Argentina often travel to Chile for medical care, while machivisit Puelmapu to treat patients. However, border restrictions persist, aggravated by discriminatory practices that limit mobility and access to traditional medicine.

The imposition of borders has disrupted ancestral practices and marginalized the Mapuche-Tehuelche people. Their peaceful struggle to defend the lawen and machi reflects their resistance to these imposed divisions and their commitment to preserving their cultural and spiritual heritage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, what is today recognized as a border is, for the Mapuche people, an open and connective space that transcends physical borders. Following the reflections of De Certeau,12 the mountain range between Argentina and Chile represents an ongoing history: a testimony of memories in constant reconstruction. This space, which predates the nation-states of Chile and Argentina, remains central to the lives of Mapuche families on both sides of the mountain range. In the Mapuche worldview, health and territory are inseparable, and the Andes (Wallmapu) embody both a living history and a place of political and affective memory. Therefore, the struggle for the lawen reflects not only a fight against imposed borders and discrimination but also a recovery of dignity and a revitalization of a worldview that sees the border as a dynamic and living territory, echoing its history and challenging the limits defined by the state.

Kaia Santisteban is a doctoral fellow in anthropology at the National University of Buenos Aires (UBA) through a scholarship awarded by the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET). She works at the Institute for Research in Cultural Diversity and Processes of Change (IIDYPCA). Since 2012, she has been part of GEMAS, a Study Group on Altered and Subordinated Memories, which addresses reflective processes of reconstructing political-affective memories in contexts of asymmetric power.

- This paper resulted from a conference given at the VIIth Seminar on Contemporary International Migrations: In-movilities and Impacts of COVID-19 on Migrations and Territories, organized by the Argentinean Network of Researchers on Contemporary International Migrations (Red IAMIC). ↩︎

- Veena Das, Critical Events: An Anthropological Perspective on Contemporary India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995). ↩︎

- José Bengoa, Historia del pueblo Mapuche, siglos XIX y XX (Santiago de Chile: Ediciones SUR, 1985); Enrique Masés, Estado y cuestión indígena: El destino final de los indios sometidos en el sur del territorio (1878–1910) (Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros, 2002); Walter Delrio, Memorias de expropiación: sometimiento e incorporación indígena en la Patagonia 1872–1943 (Buenos Aires: Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires, 2005); Claudia Briones and Walter Delrio, “La ‘Conquista del Desierto’ desde perspectivas hegemónicas y subalternas,” Runa 27 (2007): 23–48; Axel Lazzari and Diana Lenton, “Araucanization and Nation: A Century Inscribing Foreign Indians over the Pampas,” in Living on the Edge: Native Peoples of Pampa, Patagonia, and Tierra del Fuego (2002): 33–46; Pilar Pérez, “Historia y silencio: La Conquista del Desierto como genocidio no-narrado,” Corpus: Archivos virtuales de la alteridad americana 1, no. 2 (2011); and Mariano Nagy and Alexis Papazian, “El campo de concentración de Martín García: Entre el control estatal dentro de la isla y las prácticas de distribución de indígenas (1871–1886),” Corpus: Archivos virtuales de la alteridad americana 1, no. 2 (2011). ↩︎

- Claudia Briones, La alteridad del ‘Cuarto Mundo’: una deconstrucción antropológica de la diferencia (Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Sol, 1998). ↩︎

- Kaia Santisteban, Los hilos del lawen: Anudamientos entre memorias, luchas políticas y medicina mapuche (Buenos Aires: Editorial Teseo, 2024). ↩︎

- Kaia Santisteban, “Cómo la resignificación del lawen se abre camino en contextos de disenso en torno a las diferentes concepciones sobre territorialidad,” Revista Tefros – Taller de Etnohistoria de la Frontera Sur 17, no. 2 (2019): 97–123. ↩︎

- Michel De Certau, La invención de lo cotidiano I: Artes de hacer, trans. [Alejandro Pescador] (México: Universidad Iberoamericana – Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente, 2000 [1990]). ↩︎

- Lorena Cañuqueo, “Los ngutram: relatos de trayectorias y pertenencias mapuches,” paper presented at the VIth International Congress of Ethnohistory, Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, Buenos Aires, November 2005; Lucía Golluscio and Ana M. Ramos, “El ‘hablar bien’ mapuche en zona de contacto: valor, función poética e interacción social” in Antropologías Hechas en la Argentina, Vol. 1, ed. Rosana Guber and Lía Ferrero, 605–30 (Montevideo: Asociación Latinoamericana de Antropología, 2020); and Ana M. Ramos, Los pliegues del linaje: Memorias y políticas mapuches-tehuelches en contextos de desplazamiento (Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 2010). ↩︎

- Ana Ramos, “Las memorias mapuche del ‘regreso’: de los contextos de violencia y los desplazamientos impuestos a la poética de la reestructuración,” in Autodeterminação, autonomia territorial e acesso à justiça: Povos indígenas em movimento na América Latina, coordinated by Ricardo Verdum and Edviges M. Ioris, 203–28 (Río de Janeiro: Associação Brasileira de Antropología, 2017). ↩︎

- De Certau, La invención de lo cotidiano I, 127. ↩︎

- Guillaume Boccara, “Etnogubernamentalidad. La formación del campo de la salud intercultural en Chile,” Anthropological Theory, no. 39 (2007): 185–207; Andrés Cuyul Soto, “La política de salud chilena y el pueblo Mapuche: Entre el multiculturalismo y la autonomía mapuche en salud,” Salud Problema, Segunda época, no. 14 (2013): 21–33; and Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, “Las Prácticas Espirituales de Poder de los Machi y su Relación con la Resistencia Mapuche y el Estado Chileno,” Revista Chilena De Antropología 7, no. 21 (2010): 7–22. ↩︎

- De Certau, La invención de lo cotidiano I. ↩︎