Go-Betweens

A Miniseries on Youth, Migration, and Knowledge Transfer

With contributions by Simone Lässig, H. Glenn Penny, Elisabeth Engel, Brian Van Wyck, and Swen Steinberg.

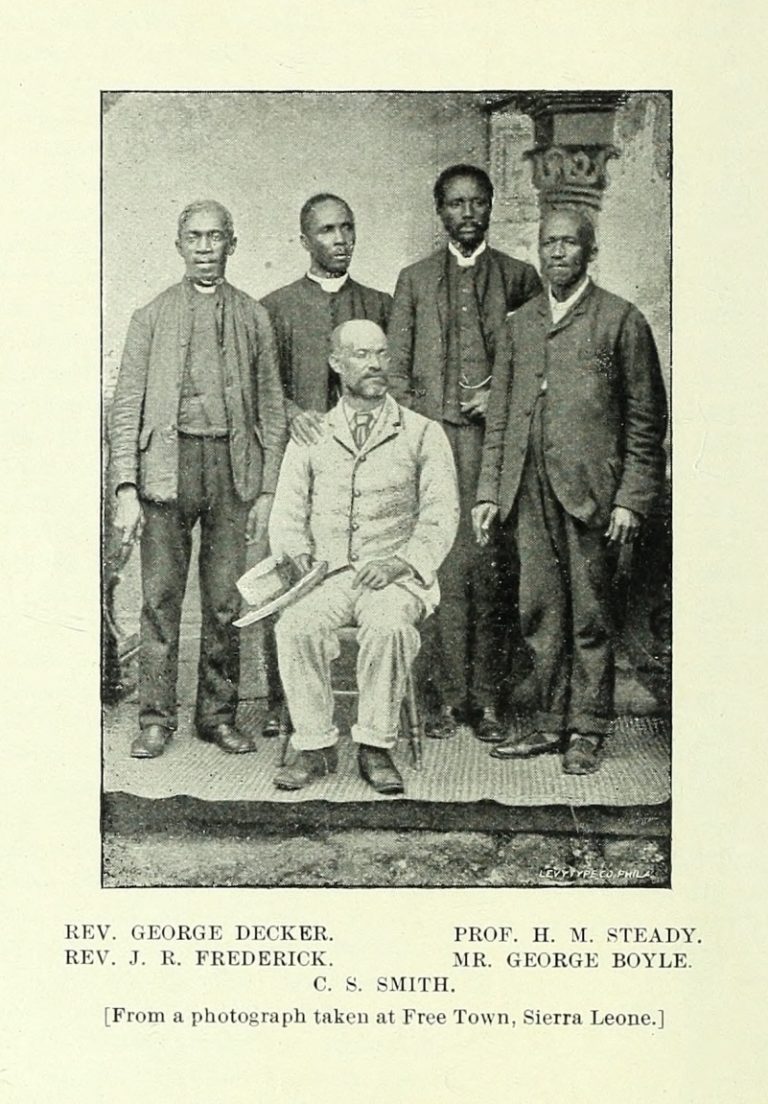

In 1921, the African missionary Reverend H. M. Steady opened a school in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Called the Girls’ Industrial and Literary School, the institution promoted the idea that young natives of the British colony should acquire gender-specific skills. Classes in household-related activities, including cooking and doing laundry, distinguished the school’s curriculum starkly from the book knowledge that American and European missionaries usually conveyed to facilitate the spread of Christianity. Steady’s school became widely acclaimed for its ambition to shape the femininity of native Christians. Local girls flocked to obtain industrial training in numbers that routinely exceeded the classrooms’ capacities, while foreign missionaries and British colonizers celebrated the school as a “very splendid” addition to the local educational system.1

The history of Steady’s school sets the stage for my effort to shed light on the problem of global knowledge transfers involving young people.2 Broadly speaking, I am interested in the role that Protestant mission schools played in enabling and structuring knowledge transfers between imperial metropoles in the West and colonial subjects elsewhere, the latter usually considered “natives” with disparate intellectual capacities. As an educational institution initiated by and for natives, Steady’s school for girls speaks to these transfers from an exceptional rather than a representative perspective. Reconstructing its efforts helps us grasp the complex impact Protestant missionary schools had on the construction of “indigenous knowledge,” including their role in the emergence of the local “go-betweens” who carried this knowledge into colonial contexts.3

Here I discuss Steady’s school from two angles. First, there is the emergence of the school’s industrial concept, which indicates missionary efforts to “import” educational philosophies from the United States and Europe into local African settings. Second, I attempt to trace how native go-betweens received and appropriated these imports on the local level. To recover the “voice” of African students, I read the sources against the grain.

The Emergence of Industrial Education in Sierra Leone

Its dual focus on industrial education and female education made the Girls’ Industrial and Literary School unique in the local landscape of Protestant missionary teaching. However, Steady did not construct this curriculum from local horizons. The school combined ideas of education from two remote and seemingly contradictory contexts. One was the African American struggle for emancipation, which presented industrial education as a stepping stone for achieving self-determination. The other was the attempt of the Colonial Office in London to reinforce British rule with a system of so-called native education, a major goal of which was the subjugation of women.

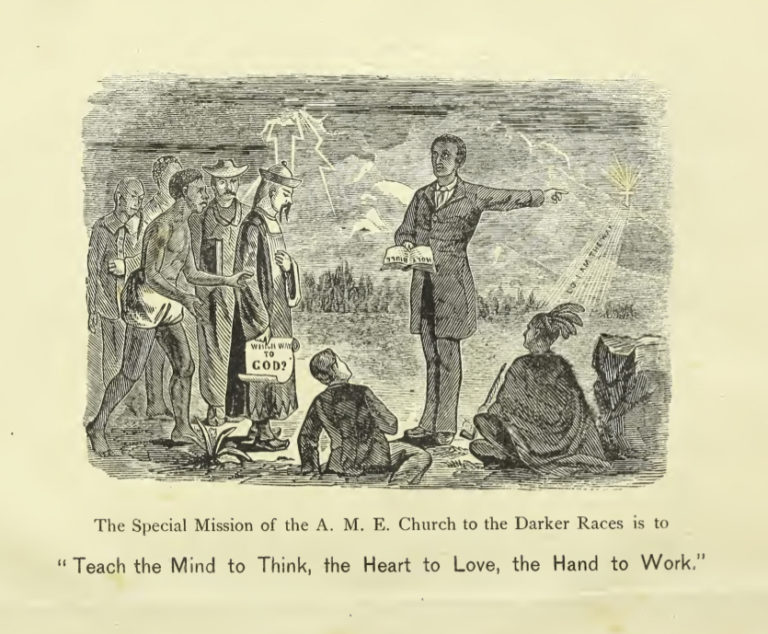

Steady encountered these starkly different ideas during his appointment as the first native African minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), an independent African American organization that had begun to pursue missionary projects in West Africa in the 1890s. Accepting a position with the AME allowed Steady to profoundly revise his image of Protestant missionary education. As a native of Sierra Leone, born in 1859, Steady had painfully learned that although he held diplomas from mission schools of various British denominations, including the Wesleyan Church and the Church of England, none of them offered career paths for African Christians. In contrast, the AME Church defined education primarily as a set of skills that allowed Blacks to improve their social status.4 These skills, as the church liked to put it, involved training “the Mind to Think, the Heart to Love, [and] the Hand to Work,”5 and they were subsumed in the concept of industrial education that was chiefly associated with the African American educator Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.6

Steady was eager to import this holistic philosophy of African American education. From the early 1900s, he dedicated his work to the erection of AME mission schools that would offer an expanded curriculum that included classes in hygiene, sewing, and agriculture all across Sierra Leone. He also saw to the establishment of an AME Seminary for Boys that focused on training native preachers and teachers. The success of these efforts to give Protestant mission schools a black appearance paved the way for Steady to seize an unexpected opportunity to reshape Sierra Leone’s educational system. In 1917, the British government appointed him to an education committee that aimed to align established Protestant mission schools with colonialist priorities. The committee aimed to fashion native women into housewives and mothers who would, in the colonialist reasoning, “substantially influence the general population.”7 Steady helped the committee to elaborate this idea by defining domestic science as a new framework for the distinct practical skills that African women were supposed to acquire. Among these skills were cleaning, homemaking, cooking, laundry work, sewing, mending, and darning as well as hygiene, child care, and motherhood, the last three taught as “secondary classes.”8

The Girls’ Industrial and Literary School made Steady’s ambiguous involvement in transferring African American and colonialist trends into Protestant mission schools explicit. Rather than epitomizing racial conflicts in the realm of native education, the school asserted itself as a unique venue that channeled African American and colonial visions into a unified body of indigenous knowledge. Over the years the curriculum emerged with some deficiencies, such as a shortage of textbooks and maps, or of classes in history, geography, and “nature study” to prepare the “biological aspect of Hygiene.”9 As Steady wrote to the home church, however, the school excelled in transmitting knowledge “in the Industrial Arts and Sciences.”10 The products African girls were making, such as textiles, “cake mixtures,” pastries, and bread as well as “excellent” jellies and preserves seemed to indicate that the school honored African American goals of industrial education. For colonial officials, on the other hand, these products showed that the school was fulfilling the purpose of “encouraging girls to take a greater interest in Domestic Work.”11

Local Responses

How did African students perceive the school, and how did they respond to the curriculum they were offered? Native voices were not recorded verbatim, but they became a theme in the records of African American and colonial observers in the 1920s and 1930s. These records concurred that the school found wide acceptance among young Africans, whether they embraced the school’s image as an African American institution or as an institute for female training in domestic science.

The school’s association with African Americans was discussed by AME missionaries as a key factor for attracting students to African Methodist teachings. The following observation was common among AME missionaries:

This faith in the American of African descent as exhibited by the native has been of considerable value to the Missionary in his efforts to expedite the work of the A.M.E. Church. The natives welcome schools as they are eager to acquire an education for themselves and for their children. Many inhabitants of remote areas have been known to travel long distances to attend schools.12

Native Africans appeared reluctant to embrace the offerings of white missionaries, especially when they concerned industrial education. African natives dismissed white mission schools that instructed pupils in manual labor as attempts to fasten them in an inferior social rank of “a hewer of wood and a drawer of water,”13 as one widespread criticism read.14 African American missionaries seemed able to convey a different sense of purpose for the same kind of education, referencing their own history of emancipation from enslavement and oppression. According to the AME missionary secretary, natives felt “that of all others, [the American Negro] is best able to help him in laying a foundation for a Christian race and a civilization, which will give him a place of religious, racial, economic and industrial freedom.”15

Beyond the celebration of African American achievements, AME missionaries and colonial observers noted that Africans adopted new ways of life once they received industrial education. As one AME missionary stated, this change of daily habits revealed itself in a “material response” that resonated across the Atlantic. Natives requested from the AME missionary department, for instance, instruments such as pianos, harmoniums, and organs, which indicated that music was beginning to play a role in their private and public lives. Others asked to be supplied with “modern cooking utensils,” typewriters, mimeograph machines, carbon paper, chalk, blackboards, maps, writing pads, composition books for courses in business training, and beauty parlor gear, thus expressing an urge for transformation that ranged from changing diets to fashion. The demand for such “modern western facilities” was a measurable but also expensive intimation of the “wholesome” reaction Africans had to the mission’s teachings.16

On the local level, female industrial education increased African girls’ social standing and income. Students began to manifest their knowledge in their appearance and performance. Colonizers saw the girls’ “orderly arrangement [and] marked cleanliness” as “outstanding features.” In addition, the knowledge that students absorbed revealed itself in their refined “elocution” and activities. Rumor also had it that “excellent” performances by musical groups augmented the school’s income when their admirers donated “decent amounts” of money to it.17 The AME Girls’ School’s choir, for example, won the Fourth Annual Singing Competition, an event inaugurated by the governor of Sierra Leone in 1935.18

Such published testimony suggests that the school’s impact went beyond African American and colonialist intentions. Students adopted industrial skills from African American contexts as a way to gain entry to lifestyles that were Western and modern, and as a means to reject white dominance in missionary education, including especially the colonialist goal to constrain pupils in their inferior status as natives and women. After all, students found in the Girls’ Industrial and Literary School a space in which they could express their preferences regarding the transmission of knowledge. The girls’ school freed them from white supervision, while giving them access to black and white bodies of knowledge. Because these knowledges were transferred by African teachers, students had a unique opportunity to engage with them in ways that departed from the educational agendas behind them. By appropriating both industrial education and domestic science, they could ultimately advance their own version of “indigenous knowledge.”

- Christine S. Smith, “The A.M.E. Church in West Africa as I Saw it,” Voice of Missions, July 1939, 6. ↩︎

- For a fuller account of the girls’ school see Elisabeth Engel, “Provincializing Pan-Africanism: The African Methodist Episcopal Church and British West Africa,” in Provincializing the United States: Colonialism, Decolonization, and (Post)Colonial Governance in Transnational Perspective, ed. Eva Bischoff, Norbert Finzsch, and Ursula Lehmkuhl (Heidelberg: Winter Verlag, 2014): 181–204. ↩︎

- Ideas of indigeneity have their own history as concepts of difference in colonial and missionary discourses. For a discussion of these concepts see Elisabeth Engel, “The Ecumenical Origins of Pan-Africanism: Africa and the ‘Southern Negro’ in the International Missionary Council’s Global Vision of Christian Indigenization in the 1920s,” Journal of Global History 13, no. 2 (2018): 209–29, doi.org/10.1017/S1740022818000050. ↩︎

- One of the best studies of the beginnings of the AME Church is Albert J. Raboteau, “Richard Allen and the African Church Movement,” in Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century, ed. Leon F. Litwack and August Meier (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1988): 1–20. ↩︎

- B. W. Arnett, Proceedings of the Quattro-Centennial Conference of the African M.E. Church of South Carolina, at Charleston, S.C., May 15, 16, and 17, 1889 (n.p., 1890), frontispiece. ↩︎

- Booker T. Washington, “Industrial Education for the Negro,” in The Negro Problem by Washington et al. (New York: James Pott and Company, 1903), 7–29. ↩︎

- “Memorandum of a Scheme for the Introduction of English Elementary Education into the Protectorate of Sierra Leone,” 1914, file C/261, box 682 (1), National Archives of Sierra Leone (NASL), Freetown, 3. ↩︎

- “Proceedings of the Conference on Female Education Held at Government House on the 29th September 1917,” file E/89, box 477, NASL, Freetown. ↩︎

- “Report on the A.M.E. Girls’ Industrial and Literary School, December 1930,” Voice of Missions (June 1931): 12–13. ↩︎

- I. E. C. Steady to W. W. Beckett, September 26, 1922, folder “Corr. Steady, 1922”; and I.E.C. Steady to W. W. Beckett, December 24, 1923, folder “Corr. Steady, 1923”; both in box 42, AME Church Records, Schomburg Archive of Black History and Culture, New York, NY. ↩︎

- “Report on the A.M.E. Girls’ Industrial and Literary School,” 12–13. ↩︎

- L. L. Berry, A Century of Missions of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, 1840–1940, (New York: Gutenberg Printing Co., 1942), 119. ↩︎

- “Wanted! Industrial Institutions,” Gold Coast Times, December 8, 1934, 7. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Berry, Century of Missions, 136. ↩︎

- Quotation in ibid., 127–28; for a list of requested items, see “Wanted,” 12, and “A Macedonian Cry: Issued by Bishop E. J. Howard, Presiding Bishop of the 14th Episcopal District for His Great and Needy Work in West Africa,” Voice of Missions, October 1938, 7. ↩︎

- By an Eye Witness, “The Girls’ Industrial and Literary Institute,” Sierra Leone Weekly News, December 26, 1925, 13. ↩︎

- “The A.M.E. Girls’ Industrial School, Freetown, Sierra Leone, Successful in Singing Competition,” Voice of Missions, March 1935, 11. ↩︎

Knowledge and the Agency of Children in Migration Contexts

Routes of Knowledge: Growing up German in Chile, 1900–50