Refugees and asylum seekers, when they express their counter-knowledge to dominant ideas about them, broaden the space of what is thinkable about refugees, the asylum system, and the political world order at large: This is the key finding of my research into how dominant ideas about refugees play out in everyday life, and especially into how refugees and asylum seekers create their own meaning about themselves in relation to these dominant ideas. In the process of expressing their counter-knowledge, they turn themselves into political actors, refusing to be excluded from the political realm. Indeed, I initiated the project in response to my discontentment with the way the media, as well as political and academic discourses, construct refugees and asylum seekers as a number, a challenge, or a threat while obscuring the individual subjects of forced migration and their agency. I wanted to find out how refugees find their (political) identity in the face of confronting powerful discourses about what a “refugee” is. In particular, I wanted to find out how refugees can still challenge these discourses both individually and collectively. To this end, I conducted an ethnographic study in Berlin and Vienna in 2019 and 2020 with refugees and asylum seekers I encountered at consultation offices, German and integration courses, refugee accommodations, theater projects, a non-governmental organization (NGO), and a federal courtroom in Vienna. I got to know people of different nationalities, age groups, genders, and social status; what they had in common, however, was that most of them had arrived in Germany or Austria within recent years, mainly after 2014. In addition to the participant observation, I conducted 36 interviews with 39 people labeled “refugees” and “asylum seekers” from Afghanistan, the Republic of Guinea, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Pakistan, Syria, and Yemen.1

Refugees’ Counter-Knowledge: Building Bridges through Music and Art

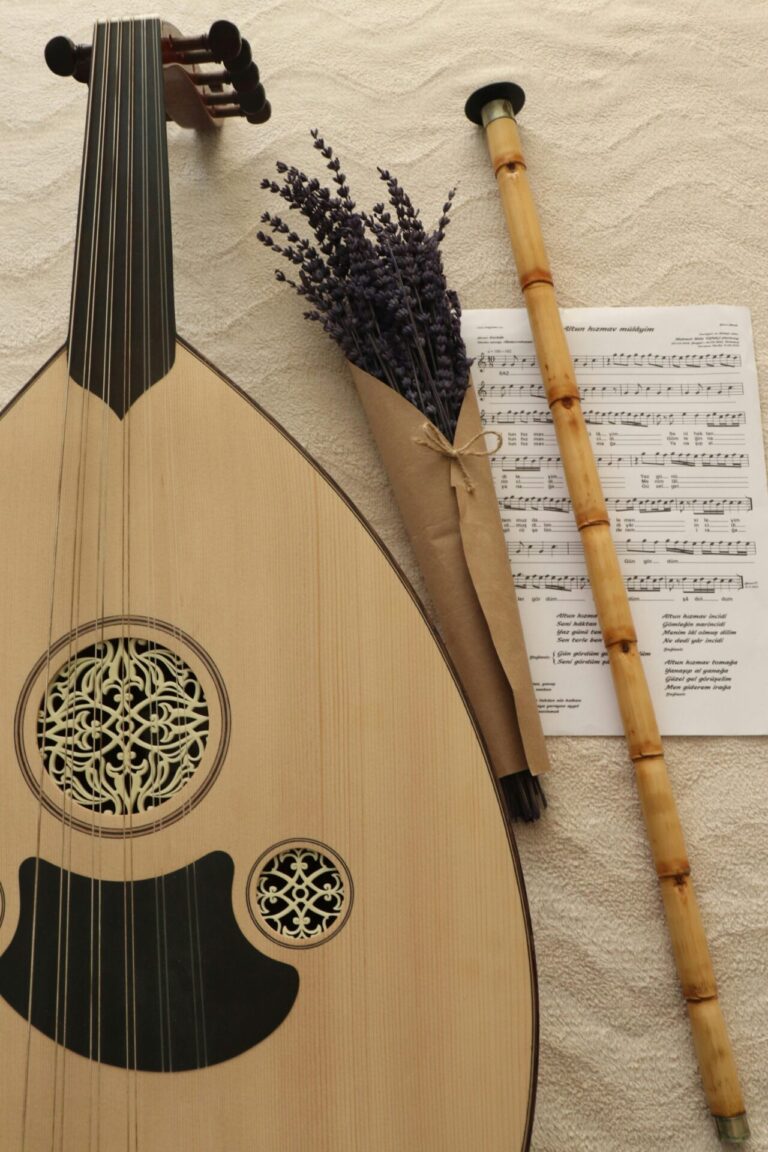

How do refugees and asylum seekers express their counter-knowledge to dominant ideas about forced migration? In my research, I found they utilize a range of stores of counter-knowledge against any type of stereotypical depiction of forced migration, but certain strategies stood out. Take the idea of refugees and asylum seekers being dangerous, threatening “Others,” regarded as criminals, terrorists, or uncontrollable in general. One strategy they use to challenge this idea is to show that rather than disturb the peace, refugees and asylum seekers are more knowledgeable about building peace due to their flight experience. The intercultural skills they acquired during various phases of flight have equipped them with more knowledge about creating and being in peace with one another. This is a type of knowledge that is practical and experiential. To mobilize this strategy, refugees have led initiatives that are directed explicitly at “building bridges,” furthering intercultural dialogue, and disseminating their intercultural knowledge in and beyond their communities. Art, such a musical and theater prodcutions and even clothing design, plays an important role in spreading this knowledge about peace. One musician from Syria, based in Vienna, for example, described himself as a musical warrior for peace to replace the imagery of the weapon-carrying soldier:

Of course, the reason that I'm here, that [is ] the common reason among all refugees, I escaped from the war, not from specific side of the people who are fighting. […] I don't want to carry a gun, you know, so I still prefer to carry my flutes, and if I want to fight, I will fight with music only.

He concretely wanted to fight for a more united world and sought to bring people of different nationalities together specifically through music. He elaborated on the idea he had in mind when he founded an international orchestra in Vienna:

I'm making music, we are, like, building bridges [… bridges ]. I feel proud myself because it's a [ …] clear message to the world that we are really one world; there is no other Earth. [… ] We are making something mixed between the oriental and Western music, and one day I played with my flute and full … oriental band, … the symphony of Mozart. [… ] Austrian music is beautiful; it's like [ … ] a bunch of flowers. There is a flower which that is red, it's very beautiful, and [ … ] the white flower is very beautiful as well. It's, there is nothing [ … ] besides the other thing; it's all music. But you cannot live your life only smelling the red one; you sometimes want to have a colorful bunch.

In saying “We are really one world,” the artist showed that he rejects a world marked by divisions along national lines and imagines a peaceful unity of all human beings. He expressed his desire to facilitate dialogue among various nations through his cultural asset: the universal language of music. Using the flower metaphor, he portrayed this lived cosmopolitanism as an enriching experience for everyone involved. Against the perception of refugees as dangerous, his orchestra uses music to tell stories of peacefully coexisting rather than endangering one another. The musician utilizes his knowledge of his abilities to connect nations and foster human communication beyond national identities and religions.

The artist also reflected on the impact of his work, citing the example of an elderly Jewish man who attended a concert and afterwards, in tears, told the musicians, “Now I know why, what do the bridges between the communities and the bridges between the nations mean, now I really know.” At the same time, the artist also faced resistance: When he applied for the program “U-Bahn Stars” (“Stars of the Subway”) funded by the Viennese public transport company, which invites artists to perform at designated areas within subway stations, he was rejected because his music did “not represent European culture.” He found this very strange, remarking that “music is an international language that everyone can understand in their own way.” I myself had implicitly assumed that music was a tool primarily for coping with emotional hardship, but during the course of my research I realized that art had a distinctly political role in expressing alternative knowledge about the world.

Refugees’ Counter-Knowledge: Not Just Learners

Another powerful expression of counter-knowledge challenged the perception of refugees and asylum seekers as perpetual students, obligated to attend more and more integration courses rather than being allowed to work. Challenging this infantilization and the perpetual schooling goes to the core of questions of knowledge itself: It means questioning ideas about who is ignorant and who is knowledgeable and reversing the roles of student and teacher. Refugees and asylum seekers were aware of their extraordinary language and intercultural skills, as well as their expertise on the asylum system, and they positioned themselves as teachers when it became clear that language course teachers or consultants actually understood less about the respective matters. Take the role reversal that happened in a workshop in Vienna. While the workshop was conducted in Arabic, the instructor was not a native Arabic speaker and had been struggling to maintain his authority. During the session, participants began praising his language skills in a way akin to how they were accustomed to being lauded for their proficiency in German. At one point, the teacher requested a German-to-Arabic translator. A participant confidently rose from her seat to take up a position next to the instructor. Her assertiveness led everyone, including the teacher and myself, to mistakenly believe she was a professional translator provided by the hosting institute. In reality, she was a regular attendee who used her language abilities to help the instructor and clarify questions from her peers. This was not an isolated incident, either: I witnessed several instances in Berlin and Vienna where students were initially asked only to assist but effectively took over the class because of their language skills. In these cases, the students not only challenged their assigned roles in the classroom by presenting themselves as instructors instead of students but also utilized their language abilities to subvert the construct of refugees as (merely) learners.

Refugees and asylum seekers reversed the student-teacher roles outside of the classroom, as well, and challenged my own involvement in making them students through (however well-meant) compliments on their language skills. A couple of my research participants mirrored this back to me by telling me, repeatedly and in mock surprise, how good my German was. They made me experience how uncomfortable and infantilizing it is to be constantly reminded that you are not quite there yet and that others are allowed to judge your progress. My interlocutors also reversed the researcher-researched relation when they examined my knowledge instead of having me extract their ideas. Tired of being asked to explain what being a refugee means to them, one of them replied, “How will you define ‘refugee’?,” leaving me struggling to come up with a good answer.

Conclusion

Dominant knowledge about refugees and asylum seekers depoliticizes refugees and their agency, casting them as too dangerous or too childlike to have any political rights. When refugees challenge the dominant knowledge about them, they challenge being suspended in this apolitical space between Otherness and the expectation to integrate. They demand to be treated normally while being different: They point to contributions they can make to a host society precisely because they bring something new to it. They contribute new and different forms of knowledge about themselves individually and refugees and asylum seekers as a whole. This then also challenges our knowledge about how we organize society and politics, where boundaries are drawn, and to what end.

![Harbisch high res[1] Young woman with chin-length wavy brown hair and blue eyes, smiling with lips closed.](https://migrantknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Harbisch-high-res1-e1750438786951-r7lg3tlyq0n6ni8or7zp1kabswv0bdixwi07cglt7k.jpg)

Amelie Harbisch is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Erfurt. Her research interests include knowledge production in international relations, ethnographic and participatory methods, forced migration, and international political sociology (practice theory, performance theories, discourse theories). The examples in this blog post are based on fieldwork she carried out for her 2025 book Making Refugees’ Political Agency Visible: Practices of the Subject.

Featured image: The cover of Harbisch’s book presenting the results of the project.

- I present the results of this project in my recent book, Amelie Harbisch, Making Refugees’ Political Agency Visible: Practices of the Subject, Interventions (London: Routledge, 2025), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003546375. ↩︎