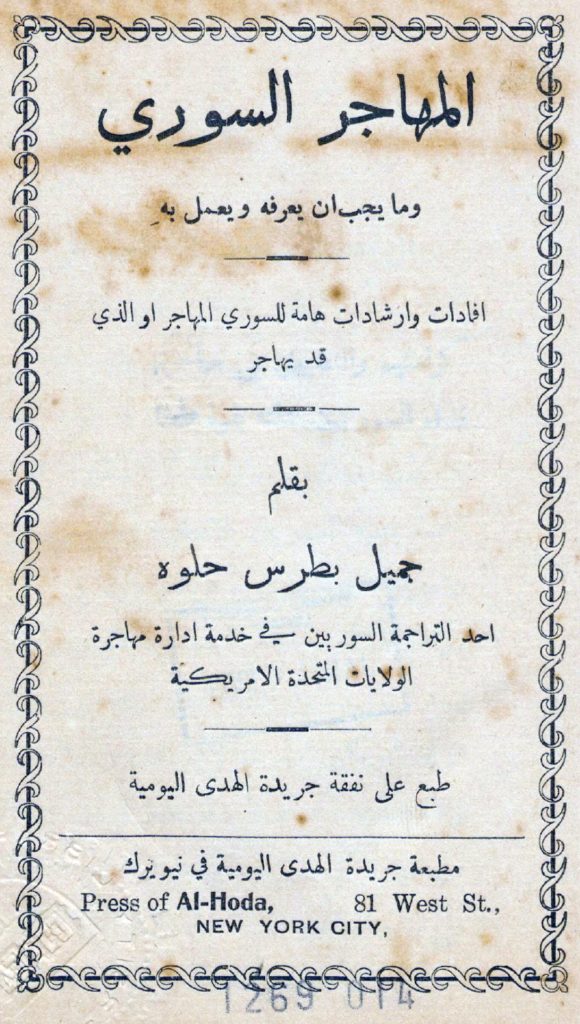

Jamil Butrus Hulwah’s The Syrian Emigrant: What He Must Know and Do appeared first in New York City in 1909.1 One of a handful of Syrian immigration inspectors working at Ellis Island to vet his countrymen for entry, Hulwah wrote the book to teach Syrian immigrants about their rights, liberties, and responsibilities in the United States.2 The country was rejecting Syrian immigrants at the port, part of a larger campaign to restrict Asian migration into the country. Hulwah believed that Syrian migrants kept getting caught up in this dragnet because of their ignorance about U.S. immigration law. Though from Asia, he claimed, Syrian migrants claimed a deep Phoenician heritage and a Semitic racial stock that should render them exempt from Asian exclusion legislation.3 Common in 1909, this racial self-positioning connected to the Syrian American legal advocacy efforts then petitioning U.S. courts for rights of access to U.S. citizenship. In the courtroom, the production of a knowledge of Syrians as dually “Phoenician” and “Semitic” bolstered the landmark immigration cases of Costa Najour or George Dow, early claimants to what is now a century-old precedent to Syrian whiteness in the United States.4

Hulwah’s booklet engaged in migrant knowledge production on a more pragmatic level, however. The Syrian Emigrant was a training manual, designed to prime Syrian migrants for the performance of identity they had to perfect before arriving at Ellis Island. In the era of steamship travel, getting to America was only half the battle. Gaining entry required the ability to achieve personal intelligibility in the eyes of U.S. immigration authorities.

In the early twentieth century, America invested in border control mostly through the policing of ethnic categories.5 Syrians increasingly faced immigration officials as individuals whose origins and stories had to be determined along the matrices of race, religion, and nationality. In claiming an identity, each Syrian coming through Ellis Island was responsible for constituting his or her own story, a narrative emplotment that was part performance and part imaginative remembering.6 The “correct” way to situate oneself at Ellis Island prior the First World War was not at all clear for Arabic-speaking immigrants, subjects of the Ottoman Empire who were nevertheless categorized as a discreet nationality by U.S. law. Advice manuals like Hulwah’s assisted them through the perils of passage, and then taught them how to perform the role of the worthy immigrant. As a genre, migrant advice booklets are a compelling genre for investigating subject formation in the Syrian mahjar (diaspora).7

In addition to orienting Syrian migrants in the history, culture, and laws of the United States, emigre advice booklets also offered new arrivals a primer in constitutional issues regarding migrant rights and self-advocacy. Understanding U.S. immigration law was a powerful tool, especially for the Syrian migrant community. As subjects of the Ottoman Empire, Syrians often confronted U.S. officials who themselves misunderstood the complex legal claims the community had in the United States. Between 1909 and 1920, Arabic-speaking immigrants from Syria, Mount Lebanon, and Palestine carried Ottoman passports but were exempted from legal restrictions placed on Ottoman subjects from elsewhere in the empire. A strong tradition of Syrian American legal advocacy achieved, for instance, access to legal naturalization in 1915, the right to travel across U.S. national borders in 1918, and a “white” racial classification—all benefits of inclusion denied to other Ottoman subjects living in America. Nevertheless, Syrian immigrants routinely had to explain their legal status to police, employers, or immigration officials who often did not understand the complexities of this Syrian nationality-within-a-nationality. Books like Hulwah’s trained Syrian immigrants on how to handle fraught conversations with U.S. law enforcement. A failure to become instantly intelligible could result in deportation, so The Syrian Emigrant was an important part of the immigrant household.

So what sorts of information appeared in Hulwah’s booklet? First, he warned Syrians that arrival in America was only the final part of a longer transit process in which they would encounter legal peril at every turn. Syrians who attempted to leave through Ottoman ports without first paying the head tax (to exempt themselves from conscription) could be arrested, their passports seized. Hulwah described storied he had heard from Syrians arriving in New York: a brother who disappeared before disembarking in Beirut; depredations by smugglers who stalked the waypoint ports in Mediterranean Europe; Syrians rejected at Ellis Island because they failed to secure paperwork from the Ottoman state. Speaking to Syrians still in the homeland, Hulwah insisted that departing migrants move through the port of Beirut, pay any taxes and fines, and carry their Ottoman passport documents with them.8

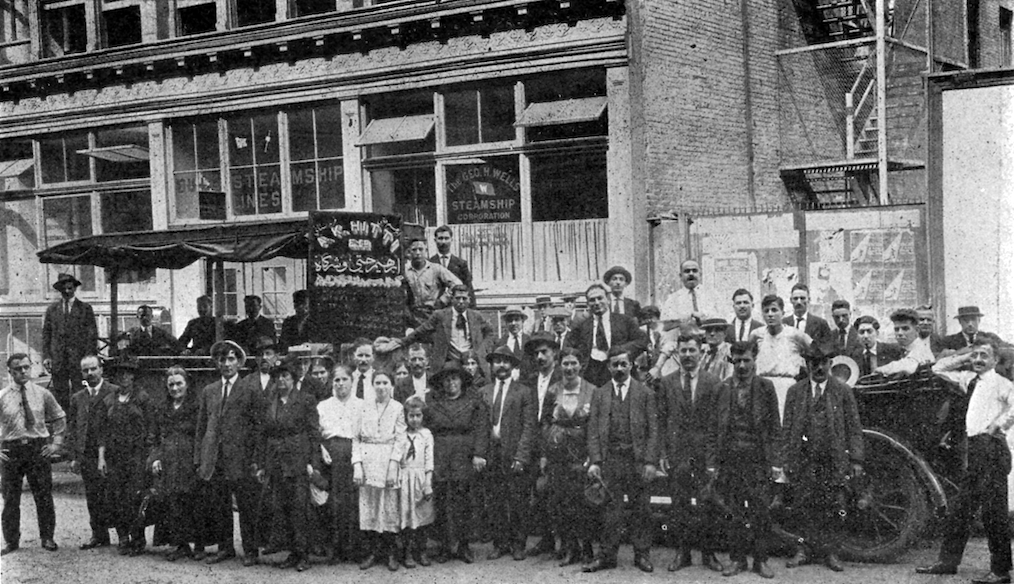

It was also important, he continued, for Syrian immigrants to have a contact with Syrian American businesses or employers upon arrival to the United States. Unlike for other Asian groups, in the Syrian case, carrying a sponsorship letter from a prospective employer was the swiftest way to ensure admittance to the United States; Hulwah included contact information for several firms in New York.9 In addition to the passport and sponsorship letter, Hulwah described the fees and medical tests that Syrian arrivals could expect, focusing especially on trachoma, an eye malady that was commonly responsible for Syrians being quarantined and deported.

Finally, Hulwah described the routinized process of government surveillance that new Syrian migrants could expect. For the first three years of one’s residence, one could expect Immigration Commission officials to make scheduled visits to Syrian neighborhoods, interviewing men and women, and checking on children’s welfare. Syrian immigrants sometimes bristled at the lack of privacy and the random interrogations, Hulwah continued, but staying in America meant knowing how to handle immigration officials and participating in state-sponsored acts of performative narration. Hulwah gave Syrian immigrants several strategies for remaining respectable in the eyes of the law enforcement agents: keep your papers on your person at all times; anticipate that repeated travel back to the homeland will inspire suspicion; avoid bars, cafes, and music halls as well as immoral activities.10 Lastly, there were dozens of Syrian American clubs in New York City, and though they provided charitable assistance, they were also under government surveillance. Syrian immigrants, Hulwah concluded, should be aware of these risks and ready to prove their community’s right to remain in America. After the three-year probationary period was complete, Syrian immigrants could file “first papers” toward legal naturalization. After declaring their intention to naturalize, Syrians faced a second waiting period of five years, and often a resumption of police surveillance.

Syrian immigrants came to America “carrying in their breasts the same American dream that Americans have within themselves,” opined Hulwah in 1909, but it was up to them to demonstrate their value to the U.S. government.11 As an immigrant immigration inspector, Hulwah’s advice to new Syrian immigrants exemplified a broader tradition of advice literature from the twentieth-century mahjar, and it offered the specific knowledge newly-arriving Syrians would need to ensure their admittance into a restrictionist United States. Today, migration historians rightly critique the mythology of immigrant “pioneers” or historiographical framings of migration through the telos of contribution, respectability, and success. But we would do well to remember that the impulse to render oneself intelligible—to step into a triumphalist American story—itself constituted a significant experience in Syrian American subject formation. The politeness of these pamphlets aside, their coercive capacity can be read as a meaningful part of “becoming American” through strategic self-representation.

Stacy D. Fahrenthold is an assistant professor at University of California, Davis, specializing in modern Middle Eastern migrations. She is the author of Between the Ottomans and the Entente: The First World War in the Syrian and Lebanese Diaspora, 1908-1925 (Oxford University Press, 2019).

- Jamil Butrus Hulwah, al-Muhajir al-Suri: wa-ma Yajibuʾan Yaʿarifahu wa-Yaʿamalu bihi (New York: al-Huda, 1909), available at https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:4336121$1i ↩︎

- Alixa Naff, Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience (Carbondale, IL: University of Southern Illinois Press, 1985), 138–39. ↩︎

- Hulwah, al-Muhajir al-Suri, 7–8. This argument was common among Syrian American legal advocates, for instance, Kalil A. Bishara, The Origin of the Modern Syrian (New York: al-Hoda Press, 1914), available at https://archive.org/details/originofmodernsy00bishuoft/page/n4. ↩︎

- Sarah Gualtieri, Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian-American Diaspora (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009), 52–81. ↩︎

- Adam McKeown, Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011). ↩︎

- On emplotment, see Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), i:45. ↩︎

- Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 11. ↩︎

- Hulwah, al-Muhajir al-Suri, 17–19. ↩︎

- Ibid., 36–37. ↩︎

- Ibid., 38. ↩︎

- Ibid., 3. ↩︎