In recent years, psychologists, pediatricians, educators, and parents alike have begun to discuss the power of playtime for children. Current wisdom pinpoints play as one of the main avenues through which children gain skills in preparation for adulthood. Playtime helps children acquire socio-emotional, cognitive, and linguistic tools for the future.1 This focus on play raises the question: What else might children learn through play?

While conducting my dissertation research on Central European Jewish refugee life in Shanghai during World War II, I came across countless memoirs and testimonies by former refugees that devoted a lot of space to childhood playtime in China. This did not surprise me because most former refugees recorded their experiences in the late 1980s and 1990s and so had been children while in Shanghai. What I did not expect, however, were the places refugees’ playtime had brought them, the people they had played with, and, most significantly, the things they had learned through their playtime.

Current scholarship at the intersection of the history of children and childhood and the history of knowledge has brought my attention to the types of knowledge that young migrants, in particular, bring, produce, learn, and translate. Scholars have shown how young migrants often move within and between different knowledge cultures, requiring them to negotiate multiple sets of knowledge at once.2 This vein of scholarship indicates that greater attention must be paid to where this knowledge transfer and production happens for young migrants. From my sources, I have become convinced of the need to consider playtime as a significant site of knowledge production for migrant children.

Play, as an activity almost exclusively for children, seems one of the most logical places to start when attempting to understand the types of knowledge that young migrants have access to and create. During playtime, children can explore their surroundings, pick up ideas from their playmates, and internalize implicit and explicit messaging from their games and toys.3 In Shanghai, Jewish refugee children’s playtime often took them into the city’s streets, where they met a host of different people, including Chinese children and adults, of course. Their play also familiarized them with local toys, which in turn gave them new insights into the landscape of the city and its environs. Through playtime, Jewish refugee children in Shanghai acquired specific knowledge about their new home through sources unavailable to adults refugees.

Shanghai Streets: Real and Imagined

To provide a bit of background, during World War II, over 15,000 Central European Jewish refugees fled Nazi Europe for the diverse and multi-ethnic metropolis of Shanghai. Whereas most countries had closed their borders to Jewish refugees, Shanghai’s unique political status as a quasi-colonial, international treaty port left the city open to refugee migration. In fact, in the late 1930s through 1940, Shanghai remained one of the only destinations in the world that did not require visas or more detailed immigration documents. This loophole meant that whole families could more easily stay together when they relocated, if they were lucky. That possibility was crucial for families that included elders and children.

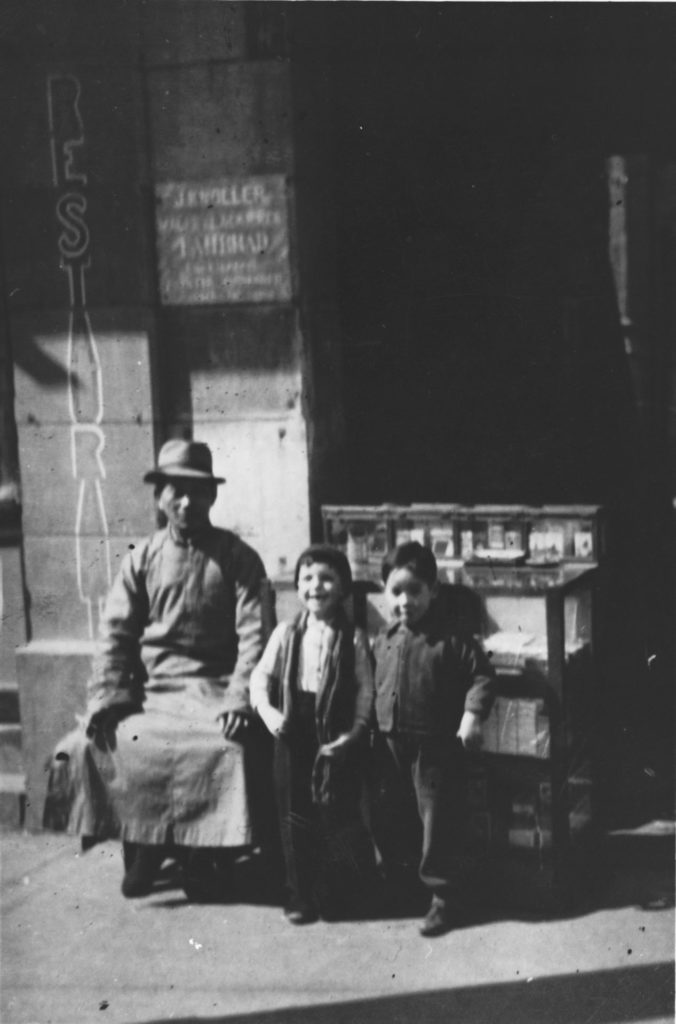

When Jewish refugee families arrived in Shanghai, children seemed to regard the city’s bustling streets with less anxiety than their parents. For adult refugees, Shanghai’s foreignness stirred stark feelings of dislocation, whereas their children regarded life in China almost as one big adventure.4 Refugee children took to enthusiastically exploring the city during their playtime.

Lorie Bellak came to China in 1939, when she was ten, from the Silesian city of Ratibor (modern-day Racibórz, Poland). Playtime took her all over her neighborhood and gave her the opportunity to make friends with the Chinese children who lived nearby. As she later recalled, “We lived in lanes in those days. You walked into a lane from the main street, and from this corridor, you went into different narrow corridors, where you had housing.” These lanes housed Jewish refugee and Chinese families alike, providing a perfect spot for all the children to play, sheltered from the foot and car traffic of the main roads. For Lorie and her Chinese counterparts, marbles was the main game of choice, and she became quite a pro. From these sessions, she even learned to speak and understand some Chinese.5 Playtime not only provided Bellak some fun, but it also became site of learning about her neighbors and their language and culture.

Playtime also afforded Hannelore Heinemann Headley, a four-year old, a chance to gain knowledge about both her surroundings and her Chinese neighbors’ interests and dispositions. After her arrival from Berlin in 1939 in Hongkou, a sector of the city where most refugees settled, Hannelore discovered in the course of her outdoor play that Chinese locals, particularly women, were often attracted to her blonde curls. She allowed such curious onlookers to touch her hair, welcoming the attention.6 After her family moved in early 1940 to the city’s French Concession, which was a more expensive neighborhood, Hannelore continued to roam the main arteries of Shanghai’s cityscape. In one unfortunate incident, a streetcar actually hit her while she was playing in the street. Although she sustained no serious injuries, she walked away with a number of cuts, bruises, and scrapes. On her walk home after the accident, she realized that a number of Chinese who had seen the accident were following her, albeit at a respectful distance. She chalked this up to the group’s mystification at a “little white girl” having survived such a mishap.7 Although Hannelore’s memories may have been filtered through her family’s own recollections later on, play did take her on journeys throughout Shanghai’s streets, where she encountered Chinese locals in more intimate circumstances.

For Ralph Harpuder, who reached Shanghai in March 1939, when he was nearly five, it was not the journeys that playtime took him on but the toys he played with that helped him become familiar with the cityscape. Most refugees could not afford boardgames for their children, but a friend of his had Shanghai Millionaire, a popular Shanghai-themed spinoff of Monopoly. Ralph remembered playing Shanghai Millionaire spiritedly every Sunday afternoon at his friend’s house.8 Later, refugee children such as Manfred and Siegfried Lobel would even craft their own handmade versions of the game, using makeshift supplies such as the back of a U.S. Army rations box.9 A closer look at the board for Shanghai Millionaire reveals the hierarchy of Shanghai’s neighborhoods as conceived in the minds of the game’s makers and presumably in the popular imagination of the city. The game makes the Bund and Nanjing Road the most expensive real estate, followed closely by Szechuen Road, Kiangse Road, and Kiukiang Road respectively.10 For children like Ralph, who played Shanghai Millionaire, such boardgames lent new insights into the city’s social geography and real estate market.

For refugee children in Shanghai like Lorie, Hannelore, and Ralph, playtime generated fun, created new diversions, and helped to pass the time. However, play also became a chance to cultivate deeper understandings of their new home, its landscape, and its people. Even later in life, former refugees spoke markedly of what they had learned and encountered through playtime. The case of Shanghai’s World War II Jewish refugee children highlights the need for us to take children’s playtime more seriously. For as Maria Montessori, one of this past century’s foremost educators, put it, “Play is the work of the child.”

Kimberly Cheng is a PhD Candidate in Hebrew and Judaic Studies and History at New York University and is currently a visiting fellow at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies.

This blog post was made possible, in part, thanks to support received from the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research and The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies.

- Anthony D. Pellegrini, The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015). ↩︎

- Simone Lässig and Swen Steinberg, “Why Young Migrants Matter in the History of Knowledge,” KNOW: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge 3, no. 2 (Fall 2019): 201. ↩︎

- Howard P. Chudacoff, Children at Play: An American History (New York, NY: NYU Press, 2007), 15. ↩︎

- Ursula Bacon, The Shanghai Diary (Seattle, WA: Milestone, 2002), 35 and 21. ↩︎

- Lorie Bellak, Interview 52185, Tape 1, 1:03:50–1:05:10, USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, JFCS Holocaust Center, 1998. ↩︎

- Hannelore Heinemann Headley, Blond China Doll: A Shanghai Interlude, 1939–1952 (St. Catherines, ON: Triple H Publishing, 2005), 52–53. ↩︎

- Ibid., 62-64. ↩︎

- Ralph Harpuder, “Ralph Harpuder,” in Shanghai Remembered: Stories of Jews Who Escaped to Shanghai from Nazi Europe, ed. Berl Falbaum (Royal Oak, MI: Momentum Books, L.L.C., 2005), 76–78. ↩︎

- Shanghai Millionaire Board Game Made by Two Germany Jewish Refugee Children, 2009.106.1, Manfred Lobel, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC ↩︎

- Shanghai Millionaire Cards, Box 4, Folder 12, Harpuder Family Papers, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. ↩︎