Texas Germans’ Migration and Knowledge

A Miniseries on Nineteenth-Century Germans’ Migration to Texas and Knowledge Transfers

With contributions by Jana Weiss, Abigail Escobedo and Simon Herbert, Jacob Johnson and Taylor Mullins, Rodolfo Alvarez and Aubrey Hernandez, Aiden Maliskas and Mark McShaneIntroduction

In 1847, John O. Meusebach was seeking to set up a peace treaty with the Native American tribe, the Penateka Comanches. Meusebach’s negotiation of a peace treaty with them was crucial to the success of the German settlement project in Texas, spearheaded by the Mainzer Adelsverein for which Meusebach served as a commissioner-general. Ultimately, the treaty sought to ensure the settlers’ safety and regulated trade relations between the two parties.1 However, entering Comanche territory was risky as one could not foresee how the Comanches would react to settlers crossing into their territory. Hence, Meusebach’s knowledge of and diplomatic skills with the Comanches were critical. He gained these from three sources, in particular: Meusebach’s predecessor as commissioner-general, Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels, the colonial director of Fredericksburg, Friedrich Armand Strubberg, and noted geologist Ferdinand Roemer, who was part of the expedition into native territory in early January 1847; all provided oral and written reports that contributed to Meusebach’s knowledge of these Native Americans.

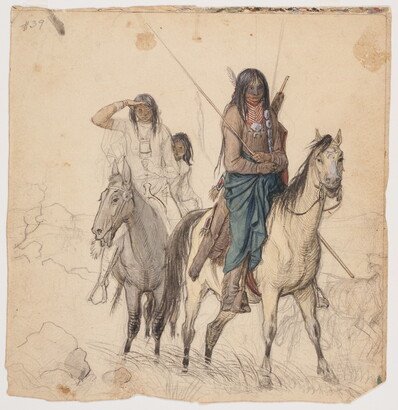

This blog post focuses on migrant art, specifically that of Friedrich Richard Petri, who was heavily influenced by his brother-in-law Hermann Lungkwitz. Even though these two artists counted among the most accomplished German-Texan painters of Native Americans and the local landscape, respectively, little research has been done on them so far.1 While a couple of scholarly works provide background on the two,2 Margaret Culbertson is one of very few scholars who has engaged extensively with their work. She argues persuasively that Petri’s art played a key role in shaping perceptions of Indigenous peoples, especially among whites, and emphasizes the “great humanity” with which he portrayed them.3 Meanwhile, Lungkwitz’s art, “romanticize[d]” depictions of the region.4 Likewise, late-Romantic era sensibilities from Europe partly defined Petri’s art and contributed to Texas Germans having a more sympathetic attitude toward Native Americans.5

The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin provides an extensive archive of primary sources for researching the impact of Petri’s art on German Americans’ perceptions of Native Americans. It houses the Friedrich Richard Petri Collection, as well as the Hermann Lungkwitz Artwork Collection, which yielded valuable insights for our research question. The Petri collection includes documents, sketches, artwork, and certificates relevant to Petri’s artistic career. This collection provides a window into the subjects he chose to paint—family members, Native Americans, and, on occasion, nature. Furthermore, it is vital to examine collections outside of his to paint the full picture of his artistic career. Petri lived in close quarters with Lungkwitz and painted alongside him, so he is a key source of information on Petri. The Lungkwitz collection contains photographs, family notes, letters, and ancestral information. These sources share the art of both men and help us visualize their lives.6

For prospective German migrants and recent arrivals, art was one of the main lenses through which they learned about the U.S., including its Native inhabitants. Petri’s depictions of them diverged from, yet also overlapped with, the “old and outworn stereotype” many observers had grown accustomed to: “real Indians” were “unpolitical and exploitative … [with] long hair, warrior mystique, and, above all, closeness to nature.” This image transformed them into the “romanticized ‘Other.'”7 Petri’s work influenced Germans’ cultural understanding and opinion of Indigenous lifestyles, potentially impacting migrants’ decisions to live in Texas. Petri’s paintings created a lasting stereotype of what it meant to be a “native.”8

German Artists Migrate to the Texan Frontier

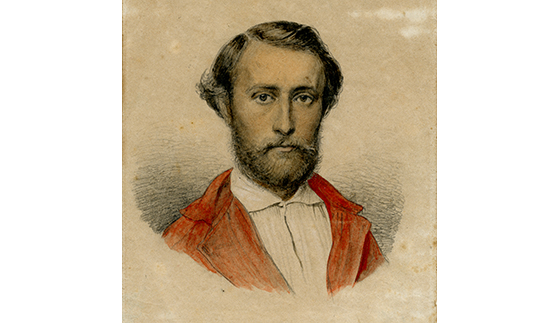

Friedrich Richard Petri was born on July 31, 1824, in Dresden, Saxony. His artistic career began at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. While at the school, Petri became good friends with Hermann Lungkwitz, his future brother-in-law and fellow painter. Along with many Germans, Petri and Lungkwitz emigrated to the United States during the middle of the nineteenth century after the 1848 Revolution. In 1852, the Petri-Lungkwitz family settled in a small community outside of Fredericksburg called Pedernales.9 During his years in Texas, Petri produced pencil sketches and paintings of several local Indigenous tribes. Unfortunately, after living and working in the state for half a decade, he drowned in the Pedernales River. His vivid paintings survived as the last remnants of his artistic legacy.

As mentioned above, Lungkwitz played a significant role in Petri’s life. Since there was not as much art in Texas as in many other states at the time, Lungkwitz was optimistic that Petri and he could make a name for themselves.10 Lungkwitz was the “hands-on figure” on the family’s farm in Pedernales, allowing Petri lots of time to indulge in his art and capture Native American images.11 Through this connection with Lungkwitz, Petri was able to create dozens of sketches and paintings that might have been delayed in their creation or never produced without him. Petri was a painter of his own merit, but, even to this day, the names Petri and Lungkwitz tend to be written about in conjunction.12 Lungkwitz was more than just a brother-in-law to Petri, and that became prevalent in the relationship they fostered and the love of art they shared.

At the same time, the artistic contrast between the two plays a crucial role within the context of our research on German-American perspectives on Native Americans. While Lungkwitz was particularly interested in painting nature and illustrating frontier life, Petri focused on depicting Native Americans, a group foreign to many German viewers. The way Petri, a white German settler, chose to paint them was informed by his outsider status and sparked the question of who has the authority to define “Indianness.”13

Petri’s Art

Art played a significant role in producing knowledge about Native Americans for the German-American community and the wider public, especially during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Petri’s art was influential for contemporary and future German-American artists, German Americans, and Germans emigrating to the United States. His works mainly depicted Native Americans in a distinct and respectful light, creating migrant knowledge for hundreds of thousands of people. However, in many ways, his works also prompted many to view Native Americans in an idealized, stereotypical way.

Through his paintings and illustrations, Petri visually documented the daily life, traditions, and ceremonies of various Native American tribes, providing a valuable glimpse into their cultures. His work could have been seen by prospective German migrants and by German Americans in the eastern United States. His art served as a medium for cultural exchange, provoking curiosity and interest among German Americans and fostering discussions about the importance of preserving and respecting Indigenous traditions.14

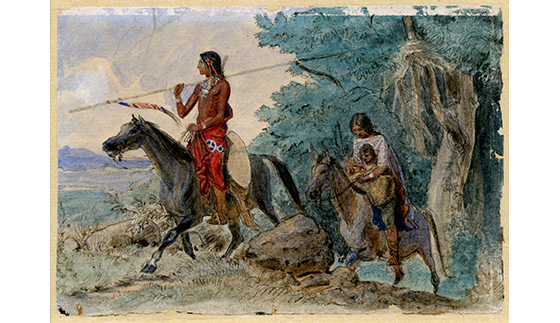

In 1852, upon arriving in Texas, Petri painted Plains Indian with Hairpipe Breastplate, now one of his better-known works. This watercolor on paper was one of the earliest known depictions of a Comanche wearing traditional clothing. The male figure looks at the ground with a calm expression; a feather sticks out at the back of his black hair. A vibrant blue sash around his shoulder and waist appears to float on the page. This piece conveys what these Indigenous people (supposedly) looked like in their authentic clothing.15

Later, in 1857, Petri began another painting entitled Fort Martin Scott. Unlike the previous work, Petri painted this one in oil and depicted dozens of people instead of just one; it also remained unfinished.16 Petri created the piece near Fredericksburg outside the building that shares its name. It beckons the viewer into a public discussion. The fort was established to protect Texas settlers and travelers from Native American attacks. The central figure is a military man speaking to a young Native woman. Petri finished painting the man, yet the woman lacks color and remains outlined in pencil marks as Petri died before completing it.

Nevertheless, the painting Fort Martin Scott survives as an integral source depicting relations between Native Americans and U.S. military officials during this era. This reflects peaceful communication as occurred in the signing of the Meusebach-Comanche Treaty in May of 1847.17 However, the seemingly friendly relationship Petri sought to display is undermined by the irony of the fort’s original purpose to protect settlers from Native Americans. This makes it hard to discern his true intention. Yet, it is reasonable to believe that viewers may have interpreted it as a peaceful, albeit unrealistic, relationship.

While Petri’s art arguably presented Native American cultures in a favorable light, it is important to consider his personal beliefs more critically. Historical records indicate that on one occasion Petri supported the policies of Native American removal, specifically of a tribe near his Texas home.18 As this was during an era of westward expansion in North America, his support reflects a problematic aspect of his relationship with Native Americans. Furthermore, because Petri spent so little time in the U.S., it is doubtful that he interacted with Native people in any depth.19 In his unfinished painting Fort Martin Scott, portraying “Indians and settlers in casual and friendly conversations,” he may have disregarded historical inconsistencies.20 Likewise, his work Plains Indian Girl with Melon presenting children serenely eating fruit does not mean he fully knew these people.

Petri’s work can be seen as a part of the broader “Romanticism” of Native Americans prevalent during this time, just as Petri’s brother-in-law’s landscape paintings were Romantic, as James Patrick McGuire points out.21 Petri chose to paint Indigenous cultures with a sense of optimism rather than struggle, which was not true to reality. He emphasized conventions and downplayed the harsh realities of colonization and dispossession. One could argue that Petri’s art may have spread these idealized notions further, which, in turn, may have misled the German-American community into “false” knowledge about Native Americans.

Conclusion

Art is one invaluable means of expressing opinions and conveying messages, ideas, and notions. This rings true when analyzing Friedrich Richard Petri’s art on the Native American people. His art displayed the historical relationship between Native Americans and European settlers, making it a powerful tool for analyzing the transfer of knowledge, stereotypes, and racism on both sides of the Atlantic. It is reasonable to argue that Petri’s artwork romanticized Native American people and their culture in a way that disguised the harsh reality of frontier colonization.22

However, prospective German migrants and German Americans may have taken away a more constructive perception of Native Americans through Petri’s artwork. Further research on how his art was perceived by contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic is needed. Petri devoted much of his artistic talent to painting these people, and his intention to represent them as peaceful and reverent people in tune with nature shows how he felt about them. His paintings of Native Americans alongside European settlers emphasized the peaceful relations that did sometimes exist between the groups, as evidenced in the prominent Meusebach-Comanche Treaty.23 Although they were not always realistic, the dozens of sketches and paintings Petri left behind from his time spent on the Pedernales provide us with a glimpse into how German Americans created artistic knowledge for (potential) migrants, helping us to further understand the impact of German-American artists on the Texas frontier and back at home.

Jacob Johnson is an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. He is interested in (primarily European) History and Religious Studies; and is a part of the Liberal Arts Honors Program at UT.

Taylor Mullins is an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin.

- Walter Kamphoefner, Germans in America (Lanham, 2021), 125. ↩︎

- Karl A. Hoerig, “German Immigrants and the Native Peoples in Western Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 105, no. 1 (2001): 422–51, is a key source of background information on Petri. It summarizes the senior bachelor’s thesis he wrote at the University of Texas at Austin. ↩︎

- Margaret Culbertson, Friedrich Richard Petri (Houston, 2016), 1. ↩︎

- James McGuire, Hermann Lungkwitz: Romantic Landscapist on the Texas Frontier (Austin, 1983). ↩︎

- The lifestyle of Indigenous peoples (attuned to nature) seemed to fit these “new” European Romantic ideals (compared to Classical-era perspectives). On Romanticism in Texas, see James C. Kearney, “The Murder of Conrad Caspar Rordorf: Art, Violence, and Intrigue on the Texas Frontier,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 123, no. 1 (2019): 1–28. ↩︎

- In addition, the Briscoe Center holds the Wupperman Family Papers, which also shed light on the artists as they lived near the Lungkwitz family. Most relevant to Petri’s story is the correspondence between Walter and Else Wupperman, Lungkwitz’s granddaughter. ↩︎

- Gerd Gemünden, Susanne Zantop, and Colin G. Calloway, Germans and Indians: Fantasies, Encounters, Projections (Lincoln, 2002), 210. ↩︎

- William W. Newcomb and Mary S. Carnahan, German Artist on the Texas Frontier (Austin, 1978), xvi, 31. ↩︎

- Culbertson, Friedrich Richard Petri, 1; Kamphoefner, Germans in America, 125. ↩︎

- Newcomb and Carnahan, German Artist, 32. Ultimately, Lungkwitz would achieve recognition in the Texas Hill Country as a landscape artist. ↩︎

- Marjorie von Rosenberg, German Artists of Early Texas: Hermann Lungkwitz and Richard Petri (Burnet, 1982). ↩︎

- Kamphoefner, Germans in America, 125. ↩︎

- Gemünden et al., Germans and Indians, 27, discuss this question. No one definition of “Indianness” can be all-encompassing. This is, of course, true of any sort of group identification. ↩︎

- Newcomb and Carnahan, German Artist, 31. ↩︎

- Friedrich Richard Petri, Plains Indian with Hairpipe Breastplate (pencil and watercolor, 1852, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History). ↩︎

- Friedrich Richard Petri, Fort Martin Scott (oil painting, 1857, Texas Memorial Museum). ↩︎

- Kamphoefner, Germans in America, 57–71. ↩︎

- Artworks by Friedrich Richard Petri (Bullock Texas State History Museum). ↩︎

- Hoerig, “German Immigrants,” 440. ↩︎

- Gemünden et al., Germans and Indians, 65. ↩︎

- McGuire, Hermann Lungkwitz. ↩︎

- Gemünden et al., Germans and Indians, 77. ↩︎

- Ibid., 65. ↩︎